By Shannon Brien

Cheek Clark Building. Courtesy The Carolina Story.

On September 17, 1998, members of the University community gathered to rededicate a building that had been standing for seventy-six years. These guests, from housekeepers to University trustees, congregated half a mile west of campus at a location that had never housed dorms or classrooms, yet had always been integral to the University’s operations. Formerly known as the University Laundry, this building was constructed in 1925 during a period of unprecedented growth at the University. As a center for campus workers for several decades, the building has a history that runs concurrent with the history of labor organizing at the University of North Carolina. The Housekeeper’s Association’s anti-discrimination lawsuit against the University in the 1990s resulted in the renaming of the University Laundry to the Kennon Cheek/Rebecca Clark Building to honor the labor activism of black campus workers that had been shaping the University since the building’s establishment.

The University Laundry

From 1917-1925, the Board of Trustees sought to construct over a dozen new buildings to accommodate both the growing number of students at the University and a more diverse set of needs. The 1916-1917 academic year saw a student population three times that of the 1911-1912 academic year, and President Edward Kidder Graham stated that the University was “in operation the whole year at full capacity.”1

As the University grew, a Visiting Committee was appointed by the Trustees in 1912 to complete a full assessment of the University’s buildings and operations. The Committee presented their findings in June 1913, and among their many recommendations, they encouraged the Trustees to create a guaranteed laundry service for students.2

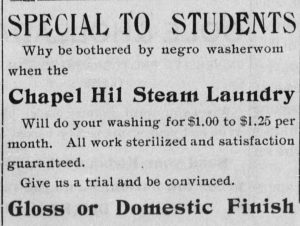

Prior to the creation of a designated laundry building, students had their laundry done for them in either the homes of individuals, mainly African American women, or in the commercial spaces of local laundry businesses. An 1897 issue of the Daily Tar Heel advertised an agent from a Raleigh laundry company looking for student patrons in Chapel Hill, indicating that businesses outside the immediate Chapel Hill vicinity saw student laundry as a lucrative opportunity.3 Another 1902 advertisement used racialized language to imply that it would be more of a convenience for students to have their laundry done in a commercial setting (Figure 1).4

In March of 1914, after the Board of Trustees approved construction of a University Laundry, those workers who independently laundered student clothing in their own homes organized among themselves and decided not to deliver laundered clothing to students “without all laundry being paid for, either in advance or on delivery of such articles laundered.”5 The necessity for such a resolution sheds light on some of the unfair treatment that washers must have faced when dealing individually with students.

By 1918, the University Laundry had yet to be built, and a Tar Heel contributor called for a University-operated laundry service to be implemented in order to better regulate the sanitary spaces in which washing was done and to prevent washerwomen from stealing or mixing up articles of clothing. “Our clothes are carried out into the houses of darkies of whom we know little or nothing,” he stated. “We do not know how our clothes are handled. Perhaps they are piled in the corner of the kitchen or living room, and exposed to filth and disease.”6 The continuance of this system proved to be a frustration for both washerwomen and students alike, and in 1920 the foundation of the Laundry was laid, with the building being completed and occupied in 1925.7

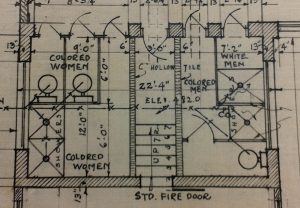

Original blueprints for the Laundry indicate that the building was expected to be a space primarily for black workers. Figure 2 shows the plans for bathroom facilities, with two toilets and two shower stalls designated for women of color, one toilet and one stall for men of color,

and a single shower for white men. While employee records from this time period are difficult to find, this construction plan clearly indicates the racialized and gendered expectations of who would constitute the University’s laundry staff.

The Reason for Renaming

The University Laundry did not make again headlines for several decades until Chancellor Michael Hooker promised to rename the building in 1998 following the settlement of the Housekeepers’ Association lawsuit. In 1991 the organization, led by housekeeper Barbara Prear, filed suit against the University alleging racial discrimination and improperly low wages.8 When the suit was filed, the starting salary for housekeepers was $11,600, approximately $1,500 below the federal poverty line.9

Over the next several years, the organization negotiated with Chancellor Hooker’s administration regarding ways to both address past grievances and ensure future cooperation on issues of race and gender within the Housekeeping Department. At one point, the Housekeepers’ Association demanded that any settlement include reparations in the form of “a one-time payment to the designated heir of all black employees at UNC between 1793 and 1960.”10 Chancellor Hooker quickly dismissed the demand as absurd; however it does indicate the housekeepers’ efforts to address a long history of racial discrimination within a single lawsuit.

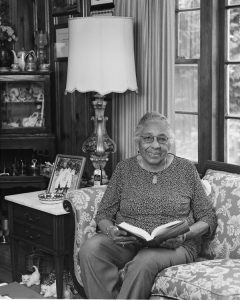

A settlement was reached in November 1997, with the Housekeepers attaining retroactive pay raises, increased career training programs, and more accessible childcare options, among other conditions (Figure 3).

The stipulation requiring recognition of African American campus workers took the form of the Commemorative Commission, made up of staff, faculty and students from a range of backgrounds. Harold G. Wallace, the Vice Chancellor for Minority Affairs, chaired the commission, and among the other committee members were: Tamara Bailey, the head of the Black Student Movement; Trevaughn Brown of the newly-established Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History; and Barbara Prear from the Housekeepers’ Association.11

The Commission’s first recommendation was the renaming of the University Laundry to the Kennon Cheek/Rebecca Clark Building “in honor of two persons who provided effective leadership for University Housekeepers during the 1930s and 1940s.”12 The Commission included newsletters and articles about the two individuals to present to the Board of Trustees in order to illustrate their contributions to the workers of UNC. On January 28, 1998, the Board of Trustees adopted the Commission’s proposal and made plans to honor the two individuals in a rededication ceremony later that year.13

Life and Work of Kennon Cheek

Just as the University Laundry was being built, Kennon Cheek began his career as a janitor at the Venable Building on UNC’s campus. Cheek grew up in Chapel Hill, the son of a University stonemason and a laundress. Cheek’s father, Rubin, was a former slave from Warren County who traveled to Chapel Hill after Emancipation.14 His early work for the University included constructing the stone walls which still surround many edges of the campus. As a University employee, he was given the opportunity to buy some land in the Northside neighborhood of Chapel Hill from the University’s land holdings. On that plot of land he built a house with a large garden and room for a cow and several chickens.

Not much is known about the background of Kennon Cheek’s mother. After she and Rubin Cheek married, she also worked for the University by taking in the laundry of professors and students.15 It is unclear how her work was impacted by the opening of the University Laundry, as she may have become an employee at the Laundry, or she may have continued washing clothes in her own home. Around 1890, she gave birth to Kennon, who was her only child. Kennon’s daughter, Marian Jackson, stated in a 2008 interview that he became employed at the University “as soon as he was of working age,” originally assisting his father as a stonemason.16 Around 1920, he joined the janitorial staff of Venable Hall, where he continued to work until his retirement in the mid-1950s.

Kennon Cheek (right) with family members, date unknown, courtesy The Carolina Story

As a janitor, Cheek often met with some of his coworkers (including Frank Hairston, Elliot Washington, and Melvin Rich) to discuss issues on the job. Over time, he and his colleagues realized that they could accomplish two very important goals with the formation of an official organization: First, they could come together to discuss common issues and submit recommendations to their supervisors. Second, they could create a space to allow for a greater camaraderie among the members of the Buildings and Grounds Department.17

The Janitors Association was founded on April 14, 1930. Kennon Cheek was elected president, a position which he held for three years.18 The Janitors Association quickly gained recognition from University officials, all the way up to President Frank Porter Graham. In the newsletter commemorating the tenth anniversary of the Association, Dr. William Coker praised the group’s willingness to cooperate with administrators.19 As the head of the University’s Buildings and Grounds Committee, Coker was the janitors’ direct connection to the administration. Cheek was also connected to Coker in another way as well: Cheek’s wife worked as a maid for the Coker household, and she often went with Dr. and Mrs. Coker as they travelled around the country collecting trees for the University’s botanical collections.20

In the tenth anniversary newsletter, founding member Eugene White recounted some of the victories that the association had achieved in its first decade. Among those were a week’s paid vacation, showers in the janitors’ bathrooms, and increased communication between the janitors and upper level administrators. White recounted how Frank Porter Graham came to an Association meeting in 1932 to inform the workers that the Great Depression was going to impact their wages, but Graham promised the janitors that everyone “would play ball together and would come through.”21 Kennon Cheek was so moved by this this speech that he made a motion for the Janitors Association to contribute $5.00 to the loan fund recently established to help students stay in school. This was the first organization on campus to contribute to the loan fund, and it furthered the strong working relationship between the janitors and administrators.

In addition to being an important figure among workers on campus, Kennon Cheek had a significant presence in the Northside community. According to his daughter, Cheek was instrumental in negotiating the 1924 land swap that brought Hackney’s Educational and Industrial School to the Northside community from its previous location on South Merritt Mill Road.22 He also helped raise funds for the rebuilding of St. Joseph CME Church on West Rosemary Street after the church burned down one Sunday just before the evening service was set to begin.23

Cheek continued to live in his house in the Northside community for the rest of his life. He tireless work coupled with diabetes wore him down quite quickly in the late 1930s, and he passed away at home in 1940. Cheek’s daughter, Marion Cheek Jackson, carried on in her father’s legacy of community organizing and represented her father at the rededication ceremony in 1998.

Life and Work of Rebecca Clark

Just as Kennon Clark became president of the Janitor’s Association, Rebecca Clark began her own work at UNC. Born around 1915 in Chatham County, Rebecca and her several younger siblings spent most of their childhood living on a farm near current-day University Lake. In an interview from 2000, Clark recalled working on other people’s farms collecting kindling and feeding chickens at seven years old.24

By 1928, both of her parents had passed away, and Clark and her younger sister were sent to live with two aunts in Greensboro, both of whom were educators. Katherine Demby, a historian who wrote her senior honors thesis on the life of Rebecca Clark, argues that these years in Greensboro had a tremendous impact on Clark’s later interest in civil rights work. Demby states that Clark’s experience in Greensboro opened her eyes to the possibilities offered by civil rights activism, as Clark encountered African Americans of various social and economic backgrounds who faced the same systems of oppression blocking their advancement.25 Clark also had the opportunity to hear various activists speak at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, such as Mary McLeod Bethune, whom Clark remembered as being influential in expanding her understandings of race relations and white supremacy.26

In 1932, Clark moved to Chapel Hill to live with other relatives, as her family in Greensboro could not afford the continued expenses of raising two teenage girls. She moved in with her relative Rosa Hawkins, who lived in a two-story house on Church Street. Clark immediately started working in the home of University Professor Dr. Vernon Howell while also enrolled in the Orange County Training School, in the hopes of one day being able to attend Tuskeegee.27 However, a bout of appendicitis left Clark a large medical debt and forced her to pick up more hours on the job and drop out of school entirely.

During her first several years in Chapel Hill, Clark worked as a domestic staff member for multiple faculty members and in various dormitories, including Old East and Ruffin. She spent the longest period of time working in the home of Dr. Vernon Howell, during which tim she earned an average of $6 or $7 dollars per week, working seven days a week.28 Demby’s research uncovered the existence of an unofficial “domestic cartel” that existed at UNC and other universities during this time period, in which faculty would collectively set the wage for domestic help in order to deflect demands for higher wages.29 Clark had Sunday afternoons off, during which time she enjoyed tennis and basketball.30

The divorce of Dr. and Mrs. Howell sent Rebecca Clark looking for a new job, which she found at the University Laundry on West Cameron. By this point in the late 1930s, Clark was married with a child and lived on Graham Street in walking distance of Laundry.31 As soon as she joined the staff at the Laundry, Clark heard talk about a union seeking to increase the wages of University workers. At first, Clark was hesitant to get involved in organizing for fear of being fired, despite her strong desire to improve the working conditions within the Laundry.32 Her husband John, however, encouraged her to speak out on those issues. He worked as a custodian in South Building and knew Frank Porter Graham personally, and though unaware of Graham’s position regarding unions, John Clark was sure that the kindhearted Graham would sympathize with Rebecca’s grievances and encouraged her to set up a meeting.33 So Rebecca reached out to her uncle, Frank Hairston, then serving as secretary of the Janitor’s Association, to see if he could make an introduction. While their first meeting did not result in any changes in University policy, Clark felt that Graham listened seriously to her concerns about the underpaid workers at the Laundry operating in oftentimes dangerous conditions.

That first meeting with Graham propelled Clark into the role of a labor organizer at UNC. She found Graham to be so supportive of her efforts that in 1942 she took over as the shop steward for the State County and Municipal Workers of America, a subgroup of the Congress of Industrial Organizations that advocated for the rights of low wage public workers.34 Building on of the relationships created between the Janitors Association and Graham’s administration, Clark was able to win wage increases for the Laundry workers, in addition to safer work spaces and more reasonable work schedules.

In 1953, Clark moved from the Laundry to the newly built University Memorial Hospital. She spent the rest of her working years as a nurse, mainly assisting new mothers in domestic duties for several weeks at a time.35 Throughout her career she also worked in her community as a civil rights advocate and is seen as a key figure in the mayoral election of Howard Lee, who in 1969 became not only the first African American mayor in Chapel Hill, but the first African American mayor in any predominately white city in the South.36 She was known for getting people to the polls by picking community members up in her son’s Greyhound bus, helping dozens of people get to the poll during many an election cycle. Even after her retirement and up until she passed away in 2009, Clark was sought out as a community leader who could guarantee a strong showing at the polls.

Conclusion

After she attended the University Laundry’s rededication ceremony in 1997, Rebecca Clark wrote to Chancellor Hooker praising him for “recognizing [workers’] efforts in keeping the houskeepers’ issues alive, and for seeing these efforts as being important in the University’s history.”37 While she anticipated the need for further conversations around race and labor at UNC, Clark saw these efforts as necessary to the process of healing for those who had been harmed by the University’s exploitative history. With the resolution of the Housekeepers’ Lawsuit in 1997, the Commemorative Committee sought to honor the contributions of African American workers by recognizing the work of two dedicated individuals whose labor organizing over the course of the twentieth century seeks to remind the community of the ongoing nature of these struggles.

—————————————————————————————————————

Special thanks to the Jackson family for assisting me in the research of Kennon Cheek. Thanks also to Su Song of the University Planroom for giving me the opportunity to explore the original blueprints of the University Laundry.

[1] President Graham to the Board of Trustees, 25 January 1917, in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[2] The Visiting Committee to the Board of Trustees, 3 June 1913, in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[3] “Oak City Steam Laundry,” The Tar Heel, 9 April 1897.

[4] “Chapel Hil [sic] Steam Laundry,” The Tar Heel, 27 April 1902.

[5] “Laundrymen Organize Trust,” The Tar Heel, 26 March 1914.

[6] “Here’s Yo’ Washin’, Boss!” The Tar Heel, 23 March 1918.

[7] “University Laundry Now Being Erected,” The Tar Heel, 30 November 1920.

[8] “Hooker pleased with Houskeepers’ Offer,” The Daily Tar Heel, 23 August 1996.

[9] “Housekeepers look to day in court after five years of controversy,” The Daily Tar Heel, 18 September 1996.

[10] “Settlement proposal withdrawn,” The Daily Tar Heel, 22 August 1996.

[11] Harold Wallace to Elson Floyd, 12 November 1997, in the Office of the Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Michael Hooker Records #40026, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Matt Kupec to Michael Hooker, 9 January 1998, in the Office of the Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Michael Hooker Records #40026, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[14] Interview with Marian Jackson by Robert Thomas Stephens and Hudson Vaughan, 29 March 2008

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] The Voice of the Janitor’s Association, 1940, Newsletter, in the Office of the Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Michael Hooker Records #40026, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Interview with Marian Jackson by Robert Thomas Stephens and Hudson Vaughan, 29 March 2008.

[21] The Voice of the Janitor’s Association, page 2, 1940, Newsletter, in the Office of the Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Michael Hooker Records #40026, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[22] Interview with Marian Jackson by Robert Thomas Stephens and Hudson Vaughan, 29 March 2008.

[23] http://saintjosephcme.com/sjcme/sample-page/our-history/

[24] Interview with Rebecca Clark by Bob Gilgor, 21 June 2000 K-0536, in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[25] Katherine Elizabeth Demby, “Rebecca Clark: the Emergence of an Unlikely Leader in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1941-1969” (Honors Essay: Dept. of History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2010), 16.

[26] Demby, “Rebecca Clark,” 17.

[27] Demby, “Rebecca Clark,” 20.

[28] Interview with Rebecca Clark by Bob Gilgor, 21 June 2000 K-0536.

[29] Demby, “Rebecca Clark,” 21.

[30] Interview with Rebecca Clark by Bob Gilgor, 21 June 2000 K-0536.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Demby, “Rebecca Clark,” 24.

[35] Interview with Rebecca Clark by Bob Gilgor, 21 June 2000 K-0536.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Rebecca Clark to Michael Hooker, 13 October 1998, in the Office of the Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Michael Hooker Records #40026, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.