UNC’s Ambiguous Memorial: A Living List of Names

By Rachel C. Kirby

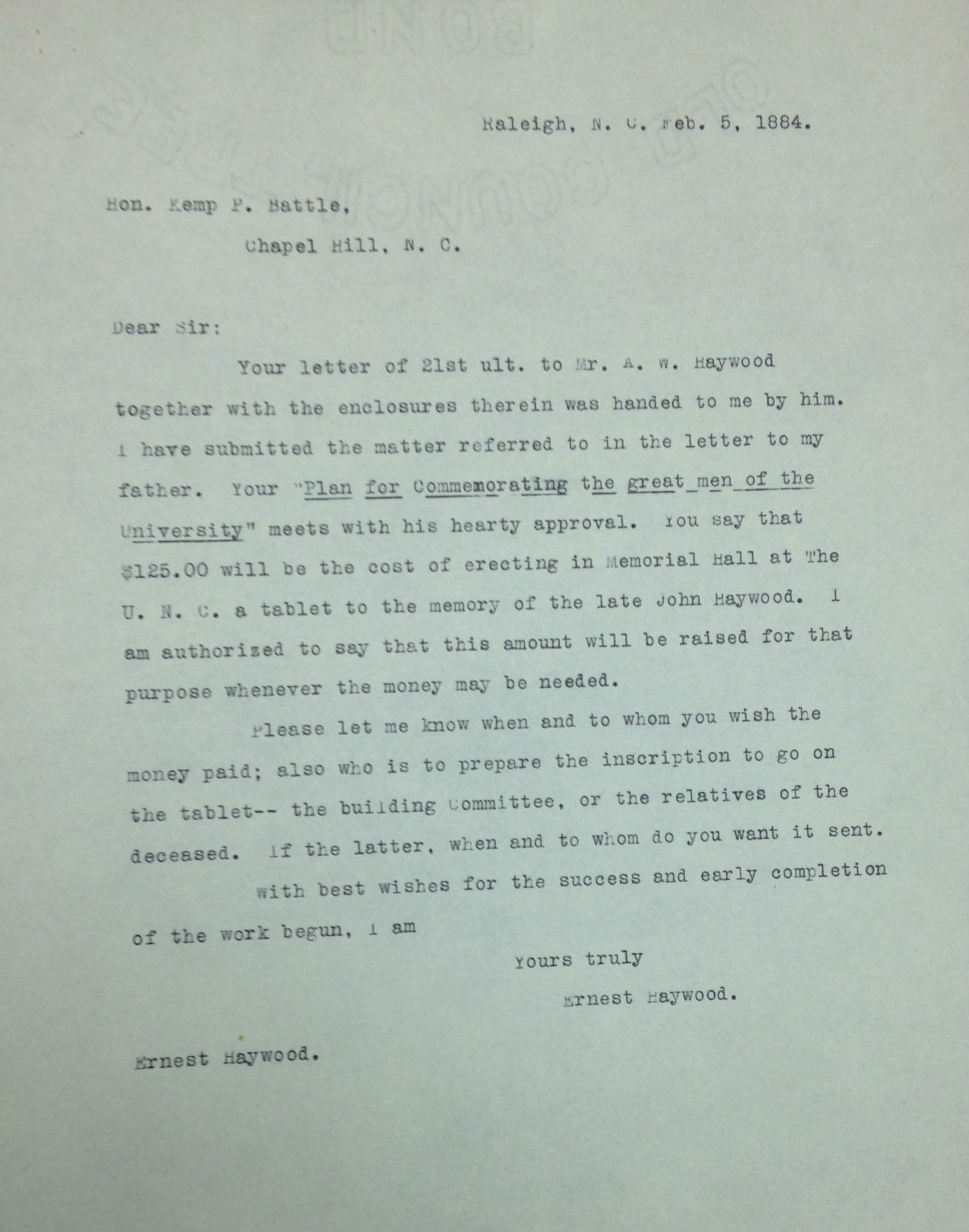

This is not Swain Memorial Hall. This is not the original building on this site. This is not the setting of annual graduation ceremonies. The name, the aesthetics, and the function of the structure that currently sits at 114 East Cameron Avenue all vary from the University’s initial intentions for an auditorium on this location. What exists today is Memorial Hall, a public facing entertainment venue and home to Carolina Performing Arts, built in the Colonial Revival architectural style, which serves the University and the larger community. The name, the design, and the function of Memorial Hall have all changed and evolved over time, leaving the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a grand and significant historic structure that is fundamentally a memorial, but one that has a history of ambiguity and redefinition of what and whom it actually memorializes.

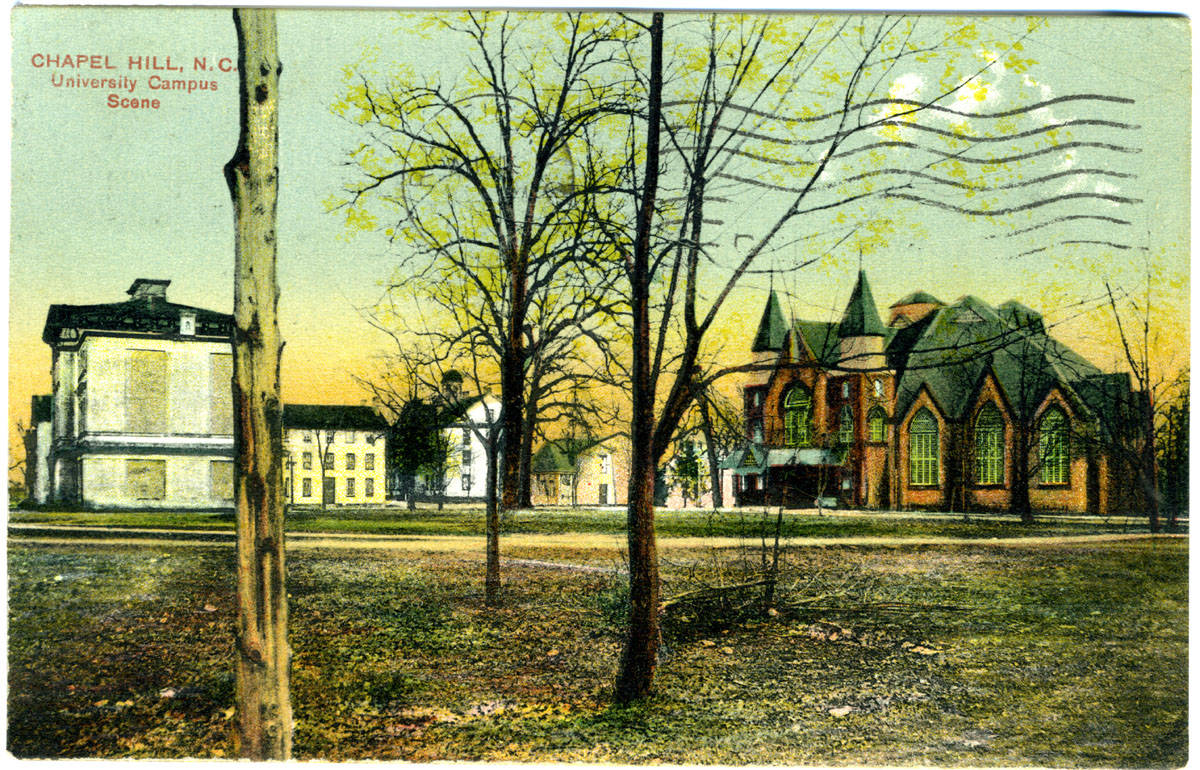

Left: Memorial Hall, 1907 postcard, Source: North Carolina Postcards; Right: Memorial Hall, 2015.

Timeline of Memorial Hall in context with other University memorials and monuments. The entries are colored coded: Blue – University, Green – Campus Memorials, Orange – History, Purple – Memorial Hall.

“A Hall for an Obelisk”[1]

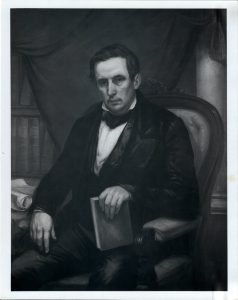

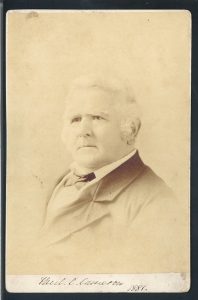

David Lowry Swain (January 4, 1801-August 29, 1868), the initial intended namesake of Memorial Hall, served The University of North Carolina from 1831 to 1868, first as a member of the Board of Trustees and later as University President. Throughout his thirty-two year tenure as President, enrollment grew, new buildings were constructed, but progress was halted around the Civil War when financial troubles led to significant turnover in University leadership. In order to negotiate the financial and political tensions, the University adopted a new elective system, requiring Swain and many faculty members to resign and seek reappointment. The new electoral system brought with it a new Board of Trustees which, in June 1868, voted not to reelect Swain. Two months later, Swain was thrown from a horse and buggy and died. His tenure at the University was generally seen as a success, though the politics and turmoil of the final year lost him some of his supporters. Outside of the University, Swain was involved with law, politics, history, and the railroad. Image source: The Carolina Story [A]

By July, these two efforts were combined, and Governor Jarvis led plans for the construction of Swain Memorial Hall, a structure that would satisfy the practical need for a larger commencement space and the honorary concerns of properly remembering David Lowry Swain.

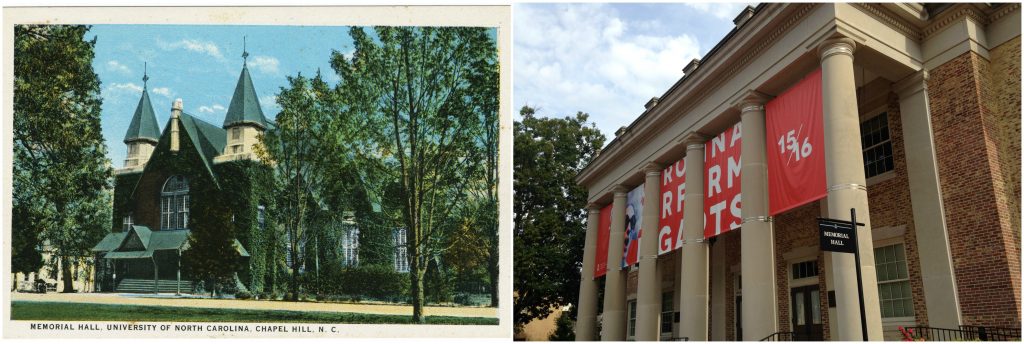

The University laid the cornerstone for Swain Memorial Hall on September 25, 1883, only three months after the initial call for construction.[4] The University spared no extravagance, fully embracing the functional and rhetorical importance of this building, and soliciting the work of established Philadelphia architect Samuel Sloan. Sloan was an adventurous architect, designing in Gothic Revival and Exotic Revival styles that contrasted drastically with the surrounding buildings on the North Carolina campus, yet in keeping with the national trends in university architecture.[5] Sloan died before the completion of the building, but the design remained reflective of his initial vision. Unfortunately, fundraising efforts lagged behind the urgency and ambition for this grand site of remembrance; before construction even began, it was clear that additional money was needed.

In the July meeting combining the efforts to create a memorial and a hall, Governor Jarvis decided that the structure would be constructed through the support of the Board of Trustees and the Alumni Association. Jarvis, however, did not request a specific sum from the Alumni, instead stating “Get what you can from the Alumni, pay it over to the Treasurer of the University, and we will try and pull through.”[6] “Pulling through” was no easy task when constructing the largest auditorium in the state,[7] and in the fall of 1883, the members of the Board of Trustees and the leaders of the Alumni Association were forced to reevaluate their fundraising methods and, by extension, the memorial function of the building.

“We must not let work come to a halt…”[8]

Paul Carrington Cameron (1808-1891) died North Carolina’s wealthiest man and, prior to the Civil War, owned the largest plantation in the state with estimates of enslaved people running from 1,300-1,900. Though not a graduate of the University, Cameron was an active leader of the Alumni Association, assisted the University financially to allow it to reopen after the Civil War, and chaired the Building Committee for Memorial Hall. He was also a large supporter of agriculture, public education, and the North Carolina Railroad. Image source: The Carolina Story [B]

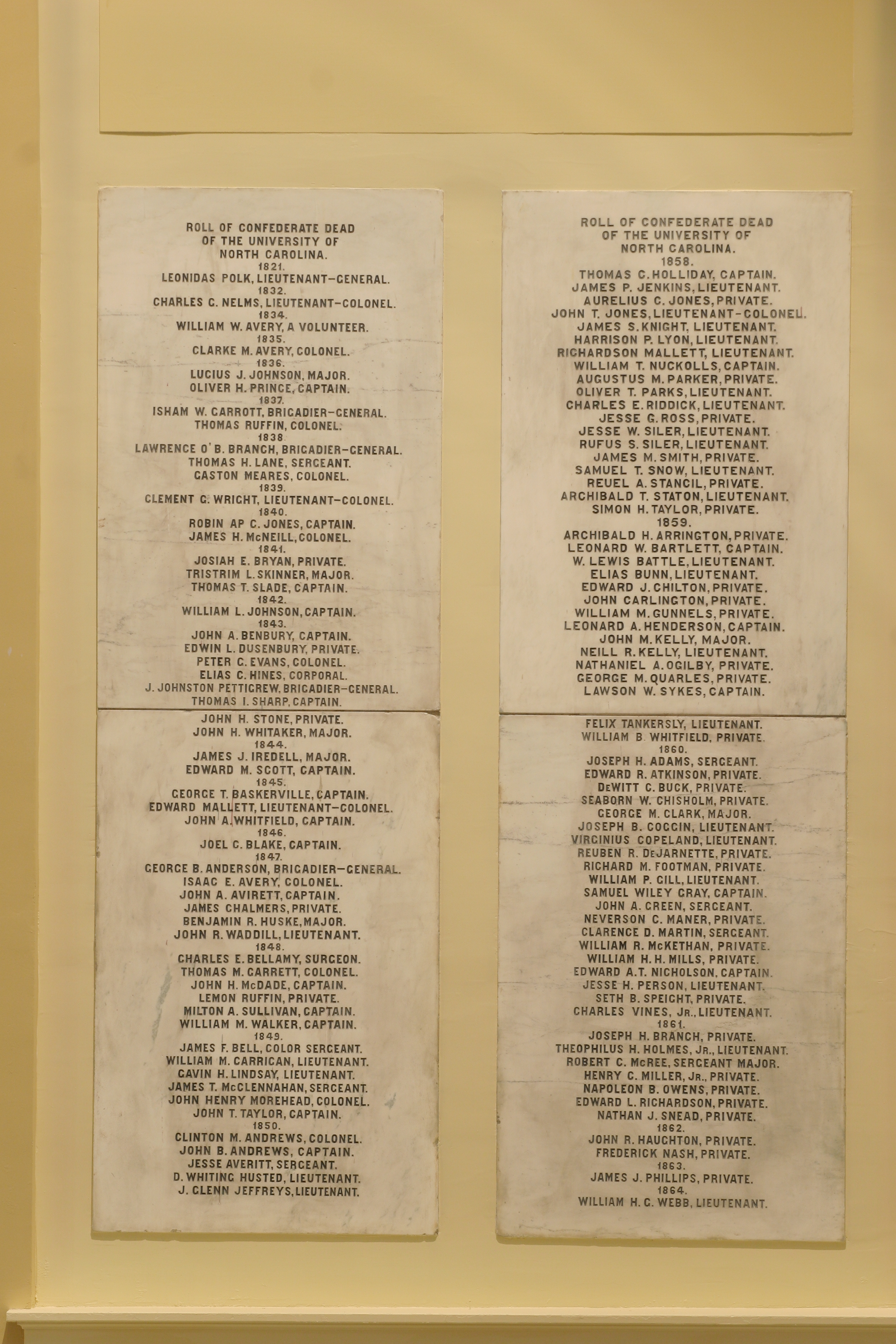

Even as construction began, the memorial purpose of the new hall was under negotiation. It remained primarily a structure to honor Swain, but expanded to include faculty and Confederate dead. At this point, however, the focus on Swain remained central to the recruitment of funds. University representatives solicited money to honor Swain’s contemporaries, those affiliated with the University, and those who fought for the Confederacy.

Cameron quickly became frustrated with the inability to raise money for the building. In a letter to President Battle on September 28, 1883, a mere three days after the cornerstone was laid, Cameron expressed the need for accuracy in assembling the list of University Confederate Dead. His concerns, however, appear to have been fiscal rather than commemorative: “It is a matter that I think of every day, and that is how we can get the men of means to give us some help to make ‘Swain Hall’ what we wish it.”[10] While he acknowledged the need to include the Confederate Dead – because this inclusion would encourage financial donations – his concern remained with the creation of a proper memorial for Swain. Later in the letter, he lamented, “I am in wonder and astonishment at the disregard of some of our most prominent wealthy and influential men! I ask myself is it poverty, indifference or meanness.”[11] What Cameron failed to acknowledge was that, unlike him, many of North Carolina’s wealthy men had not maintained their money in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The Board of Trustees shared Cameron’s concern of accuracy in the list of Confederate Dead. In a letter written on October 16, 1883 made out simply to ‘My Dear Sir,” William L. Saunders, the Secretary of the Board of Trustees, wrote “It is proposed to place a Mural Tablet in Swain Hall being built at Chapel Hill, to the memory of such University students as were killed, or who died in the Confederate Service during the late War, and an effort is now being made to secure an accurate list for that purpose.”[12] This letter highlights the relationship between the University, the alumni, and the community. The Board of Trustees paid for and organized the tablets, the Alumni Association, led by Paul Cameron, advocated for the tablets, and the greater North Carolina community contributed to the accuracy of the list. At this point, the qualifications for memorialization were controlled by the University, limited to Swain, Swain’s contemporaries, and the Confederate Dead. The method for securing names, however, marks a recognition in the importance of public input, and opens conversation that was later expanded beyond the Confederate Dead.

As autumn progressed and funds ran out, conversation shifted away from raising money specifically to honor Swain and the University’s Confederate Dead. By mid-December 1883, as construction on the Hall was suspended, President Battle and Paul Cameron began soliciting money to sponsor tablets honoring additional notable North Carolinians. At this time, “notables” were exclusively white and overwhelmingly male. The recruitment letters targeted the wives, children, and family members of men who were known throughout the state for their public service. The only women eventually listed were remembered primarily for donating money or land. The tablets served dual intentions: to fund the construction of a needed building, and to create a list of historically significant people who would be remembered by future generations of North Carolinians.

“To the Memory of such Distinguished Citizens”[13]

By the start of 1884, letters began pouring into Chapel Hill responding to requests for money to raise memorial tablets to men of prominent standing in North Carolina. The responses, however, were not concerning “Swain Memorial Hall,” but addressed a wider array of sentiments and causes.[14] They came from the wives, children, and family members of “those who had been associated with the institution in the past, and who, by honorable lives, either civil or military, were deemed worthy of commemoration within these walls.”[15] Memorial Hall was no longer a memorial to Swain and his close affiliates; it was now a memorial for the people of North Carolina funded by the people of North Carolina.[16]

- Fred A. Toomer

- The Misses Nash

- Thos. Kenan

- Mrs. L. O’Branch

- John P. Branch

- Kerr Craige

- Walter L. Steele

- R. Y. McAden

- B. R. Moore

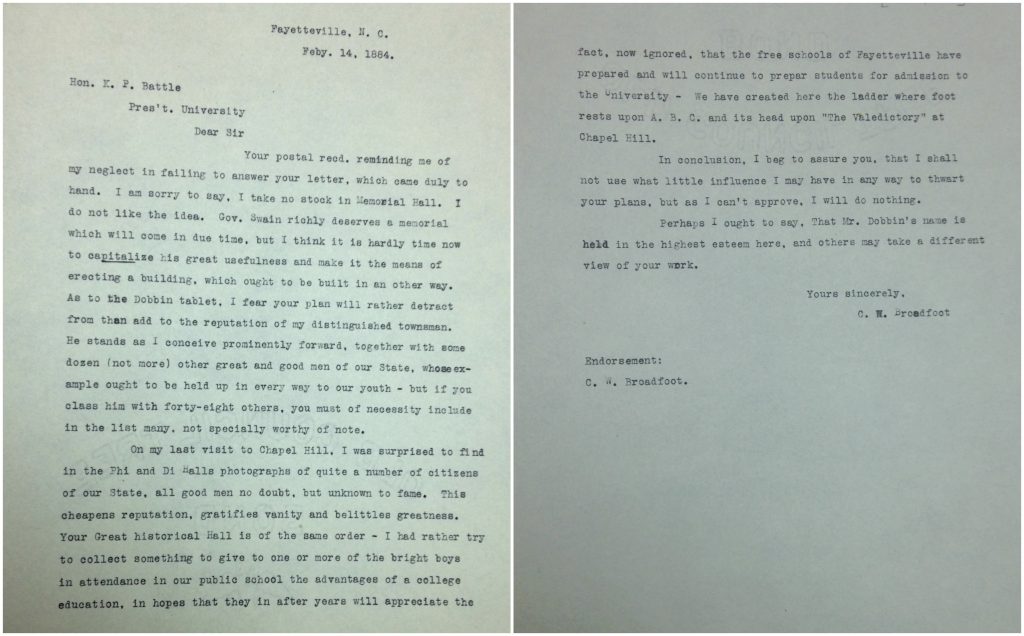

Responses to the requests were mixed. Mr. Steele supported the new purpose of the hall, and wrote “Glad you have abandoned the Swain idea. Personally, I would give something for a Chapel- when I get the money to spare- but not one cent, if it is to be called Swain Hall. Indeed, I would not go in it, at Commencement, with such a name.”[17] Others were not as pleased with the decision to drop the focus on Swain. C. M. Broadfoot expressed his displeasure with the project, and he wrote “I am sorry to say, I take no stock in Memorial Hall. I do not like the idea. Gov. Swain richly deserves a memorial which will come in due time, but I think it is hardly time now to capitalize his great usefulness and make it the means of erecting a building, which ought to be built in an other [sic] way.”[18] And others still expressed a concern that those who were “notable” would lose their status if they were placed in a memorial with men who were less worthy and accomplished.[19] The letters suggest that support largely surpassed disapproval, though some oppositionists may have not been as vocal with their opinions as Mr. Broadfoot.

Despite the occasional displeasure with the decentering of Swain, the collective community represented in the received letters appeared pleased with the ability to honor their loved ones with tablets. They also seemed pleased with the larger rhetorical purpose of the hall, supporting endeavors to expand the memorial beyond Swain. On January 18, 1884, Mrs. L. O’B. Branch wrote,

“Your esteemed favor came duly to hand, and allow me to add, was most highly appreciated. The undertaking is a laudable one, and assumes cooperation on the part of every patriot of the State. To perpetuate the memory of those noble spirits who – gallant – State pride – and generous action, homeless- such an inheritance to the rising generation, is worthy the consideration of the survivers [sic]- and your proposition to place Memorial Tablets in a Hall at the University of the State to aid in the minds of the young men of N. C. their exalted interest- gives a sure means of accomplishing the purpose.”[20]

Mrs. Branch understood that this building was more than a list of names. It was to be a record of a particular and desirable memory, and a source of inspiration for future generations of leaders of North Carolina. The building would be the physical manifestation of ideals to which North Carolina could strive: generosity, nobility, patriotism, purpose. Memorial Hall was funded by supporters of the South in honor of those who fought for the South or otherwise served the State; it was a marker of the past that was built to exist into and shape the future.

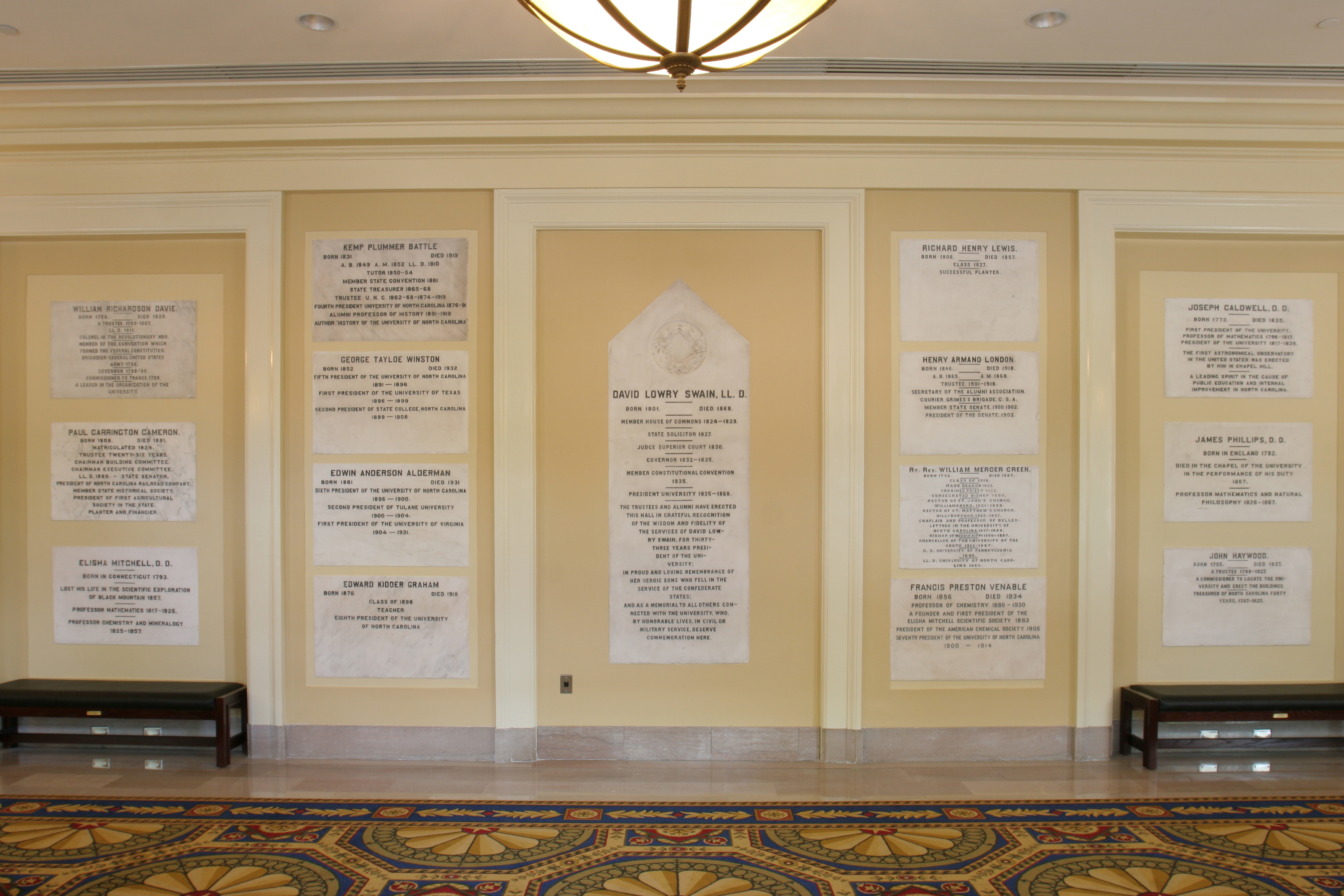

The placement of the tablets in the original 1883 building was ordered and strategic: the tablet for President Swain was largest and most centrally placed in the lobby, flanked on either side by President Caldwell, Dr. Elisha Mitchell, and Dr. James Phillips. Just below Swain’s tablet were the tablets to the University Confederate Dead.[21] These central tablets were those paid for by the University, and displayed the names that University leadership found worthy of inclusion regardless of external sponsorship. Surrounding these tablets on either side of the lobby were an additional ninety-eight crowd-funded tablets, organized by date of death of those honored. Across from these walls were tablets honoring the donors of the land on which the University was built, and finally, a tablet on the east side of the rostrum listed the University’s female benefactors.[22]

Those who gave money hoped to guarantee that their name, or the name of a loved one, would be permanently remembered as a crucial part of the history of North Carolina and of this University. But not all individuals who wanted to donate funds for honorary tablets were able to contribute immediately. North Carolina was still dealing with the aftermath of Reconstruction, and many “prominent” individuals no longer had the wealth they possessed prior to the Civil War. Fortunately for them, the collection and display of tablets did not cease upon the conclusion of construction and the 1885 dedication of the building. In 1923, the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees named a committee of members who would nominate names for inclusion in Memorial Hall, noting the limited space and the importance of reviewing the credibility of those suggested for tablature.[23]

The archives leave the process for nomination and review relatively unclear. What is known is that a committee of the Board of Trustees, a select group of relatively wealthy white men, had the curatorial control over the names incorporated in this public-facing, and supposedly publicly assembled, memorial. Consequently, the insertion of a tablet and a specific name was not only marked by financial privilege but by access to privileged knowledge. The committee continued to consider suggestions for memorial inclusion for many years, halting their efforts sometime in the late nineteen-teens, possibly due to a decreased confidence in the longevity of the Hall itself.

Click here for the Inaugural Proceedings, 1885.

“Doomsday For Memorial Hall”[24]

Less than fifty years after the opening of Memorial Hall, its survival was called into question. In 1918, President Edward Kidder Graham outlined a plan for the University to expand its buildings to create a unified campus landscape, and the plan was carried out through the 1920s. The Gothic Revival structure stuck out as dark and dated when compared to the traditional white columns and light marble of the newly built Colonial Revival buildings. The clashing aesthetics may have been reason enough to demand the demolition of the original building, and requests for a new building increased as classically inspired buildings continued to decorate the landscape.[25] By 1930, the flying buttresses and pointed arches of the Gothic building would have been more at home at the recently renamed Duke University than at its location in Chapel Hill.

Memorial Hall, New West, and Old West, c. 1911. Source: North Carolina Postcards.

The archives suggest, however, that the old Memorial Hall was not simply problematic because of its appearance. On December 7, 1929, John H. Gregory, Professor of Civil Engineering at The Johns Hopkins University submitted a document titled “Report to Dr. H. W. Chase, President University of North Carolina on the Present Condition of Memorial Hall and as to the Practicability of its Repair.”[26] Gregory references previous reports, the conditions of the arches, and the deterioration of timber support beams to ultimately conclude “The building is not a safe structure.”[27] Coupled with statements from Fire Marshals, this report suggests that there were significant concerns surrounding the usability of the building which contributed to the desire to tear down and replace Memorial Hall.

Click here for John H. Gregory’s full report.

This 1930s reconstruction of Memorial Hall shared similarities to the process of constructing the first building in the 1880s. Like the initial construction, there are records of public opinion on the matter. For the second building, however, these are not in the form of letters agreeing or declining to offer financial assistance. The majority of these records come from newspapers published between 1927 and 1930. And like before, public sentiment varied, though the discussion focused primarily on aesthetics and the maintenance or destruction of the building, rather than on the memorial purpose. On May 19, 1927, The Tar Heel republished an article originally produced in the Raleigh Times titled “Let Memorial Hall Retain Its Distinctive Ugliness.” This opinion piece stated,

“We believe that University alumni will share with us the hope that Memorial Hall be not altered, changed, or remodeled, as the building committee has suggested is possible. It is said that by changing the front, lowering the floor and otherwise practicing architectural dentistry on the old pile, it can be made quite presentable in appearance. The idea then would be to devote it to use for gatherings, as at present, and as a memorial place for alumni participants in all wars.”[28]

This letter suggests that the building should be kept as is, a place of memorial and a place of consistency. The author of this letter, though, holds the idea that Memorial Hall is a space for remembering alumni of all wars. Previously, rhetoric surrounding Memorial Hall focused on the Civil War and on “notable North Carolinians.” This letter suggests an expansion upon the memorial purpose of the building: an expansion requested by a public audience, rather than one decided upon by University donors or leaders.

Even editorials that argued for the removal of the current building recognized the importance of its symbolic meaning. An article published in The Daily Tar Heel on October 31, 1929 claimed that sentiment would be the only reason for maintaining the structure, but argued that sentiment alone was not a worthy motive. The functional needs of a hall would be better met, the editorial claimed, by a new structure that was not “hideous from an aesthetic standpoint.”[29] The building was nothing less than an “architectural monstrosity” which needed to be replaced as soon as possible.[30] Public opinion called for the abandonment of the Gothic and Eclectic Revival architectural styles, a request that was fulfilled when the original building was demolished in 1930. The new building carried forward three common elements from its predecessor: the location, the name, and the memorial tablets.

Old Antebellum in Design[31]

The new Memorial Hall was conceptualized during the 1920s, a decade that saw the construction of Polk Place, Spencer Dormitory, and the Carolina Inn. The Southern Colonial architecture elevated and idealized an antebellum past, a past that was actively and intentionally celebrated across the landscape of the South during the end of the nineteenth and the early part of the twentieth-century.[32] Throughout the region, the United Daughters of the Confederacy fundraised and campaigned for the installation of monuments to Confederate soldiers and to the “Lost Cause” they fought to preserve.[33] The group supported a narrative of a romanticized past in which the Antebellum South was glorified and celebrated, and their campaigns constructed a memorial landscape to the Civil War that is still largely visible.[34] The new Memorial Hall and its embodiment of Lost Cause rhetoric and symbolism preserved and recast the Civil War as a source of continued glorification.

1930 was not a promising moment to build a new structure. In the midst of the Great Depression, the nation and the South faced significant financial instability. Just as the University persevered through challenging economic circumstances to build the first Memorial Hall, the reconstruction presented an opportunity to communicate the stability of the University and of the State. In both iterations, the decision to finance the memorial structure emphasized what University leaders found valuable. They valued the names of those who had served the state politically and militarily. They valued President Swain, Elisha Mitchell, and James Phillips. And they valued the Confederate Dead.

The central tablet to Swain, located in the main lobby. Photo courtesy of Carolina Performing Arts. 2005.

Before the original hall was destroyed, the memorial tablets were removed for safe-keeping. They were returned to the new Memorial Hall before it reopened in 1931, but the tablets were not all hung in the same order and position. The tablet to Swain remained the central feature of Memorial Hall, the most visible tablet upon entering the venue from the main doors. The other tablets were then scattered throughout the building’s public spaces, across the multiple hallways and stairways of the building’s first two floors. The most notable change in the new building, however, was the placement of the tablets commemorating the University Confederate Dead. These tablets were no longer positioned prominently below the tablet for Swain. They were not displayed in the lobby, in a hall, or in a staircase; they were placed in the auditorium, where they remain today.

Photos courtesy of Carolina Performing Arts. 2005.

Four tablets list two-hundred  and sixty alumni and students who died fighting for the Confederate States of America. In 1931 they were hung, and they still hang, on either side of the auditorium stage, elevated far above the audience’s seats, and blended into the pattern of decorative molding and framing featured throughout the room. These tablets are now isolated from the rest of the memorialized individuals, listed together, distinguished and elevated, but made notably inaccessible.

and sixty alumni and students who died fighting for the Confederate States of America. In 1931 they were hung, and they still hang, on either side of the auditorium stage, elevated far above the audience’s seats, and blended into the pattern of decorative molding and framing featured throughout the room. These tablets are now isolated from the rest of the memorialized individuals, listed together, distinguished and elevated, but made notably inaccessible.

The new placement of these tablets creates conflicting effects. For one, the tablets are granted a physical prominence denied to all other names included in the memorial building.

Their high position, however, obscures them from visibility. They are not on eye level, and they are frequently in shadow, as the auditorium is dimmed whenever in use. The names are far away, small, and unreadable from the seats. These tablets are simultaneously prominent and invisible, elevated and overlooked, much like Memorial Hall itself. As a memorial, both the tablets to the Confederate Dead and the building in its entirety are large, centrally located, and publicly facing, but their meaning and content frequently remains hidden, out of sight and out of mind.

“Further Opportunities for Honoring”[35]

New Memorial Hall brought with it a “situation [that] has altogether changed now.”[36] The committee that dealt with decisions concerning tablets, names, and remembrance resumed their activities, no longer needing to delay additional memorials due to fear of renovation. The Hall could once again be a living memorial, funded and curated by the people of the University.

But the process for submitting names and procuring tablets has largely been lost from record. An undated document mentions a meeting in February 1932 that authorized “that the following distinguished alumni and a record of their services to the University and the State should now be perpetuated by the erection of suitable memorial tablets in the reconstructed Memorial Hall of the University of North Carolina.”[37] The record then lists nine names for memorialization, all but one of whom is now featured on tablets in the contemporary hall.[38] Records also show that there was conversation about including tablets to UNC’s World War I Dead. In 1944 the Alumni Association established a fund for the project, but such tablets never appeared.[39]

Correspondence dating from the mid-1920s to the late 1950s shows that donations came in and tablets were continually added for at least twenty-five years after the reconstruction of the building. Some of these tablets were celebrated with dedication ceremonies, and were placed on the walls in specific locations selected by the family members.[40] And for many years, requests were submitted with urgency, as people feared that the Hall would fill up and their loved ones would be excluded from remembrance.[41] There is no definite answer, though, as to why, when, or even if the Hall officially stopped taking recommendations for tablets, again leaving the requirements and intentions of the memorial ambiguous.

“We Expand This Remembrance”[42]

The auditorium of Memorial Hall during renovations, 2002. Tablets to the Confederate Dead are visible to the right. Photograph by Catharine Carter.

Memorial Hall remained in this ambiguous and seemingly unchanged symbolic state for forty years, and the interpretation of the structure largely remained static.[43] Following previous trends within the building, the memorial purpose was again called into question at a time of renovation and construction, this time in the early 2000s. The building did not have air conditioning and lacked many of the features necessary for a leading entertainment venue. It closed in 2002 for updates, and the doors remained closed for three years.

Debates arose around the rules and qualifications for inclusion on the lists of honorees, again under negotiation in an effort to recruit funds. Just ten days after the September 11, 2001 terror attacks, The Memorial Hall Transformation Campaign Committee met to discuss the new renovation. Included in the meeting’s minutes is advice on how to solicit money: “Recognize that this is a hard environment in which to raise money. The economic slowdown and political and military uncertainties caused by last week’s devastating events have made fundraising difficult. Encourage them to persevere because this project is so important to the University.”[44] Later, the minutes note a discussion around the inclusion of a list memorializing alumni who died in the recent attacks. No such tablets were added, but this conversation recognized the fluidity of the memorial purpose and noted the public’s need to acknowledge and remember recent events.

When the newly renovated building was again dedicated on September 8, 2005, Chancellor James Moeser spoke, sharing the history and future of the building’s memorial purpose:

The first Memorial Hall was built over a century ago, in 1885. The second building, this one, opened in 1931, and was dedicated to the memory of David Lowry Swain, North Carolina governor from 1831 to 1835, and president of the University from 1835 to 1868. It was also dedicated to UNC alumni who died in the Civil War and World War I, as well as outstanding Carolina alumni and North Carolinians. Tablets on the walls bear many of their names. As you can see, the tablets remain, in the auditorium and throughout the lobbies and new additions. Today, as we ‘re-dedicate’ Memorial Hall, we expand this remembrance to all members of the university community who lost their lives while on active duty serving their country.[45]

Previously, the World War I memorial dedication was somewhat unknown, but it was reinforced in 2005 and verbally expanded upon to include additional military deaths. This claim distances the Hall from its previous association with “notable North Carolinians,” distinctly intertwining the memorial function with the military, but increasingly distanced from singular ties to the Confederate cause and the Civil War.

In November of 2005, just two months after Memorial Hall was reopened, the University dedicated the Unsung Founders Memorial, a stone table held up by 300 bronze figures. The table’s inscription reads “The Class of 2002 honors the University’s unsung founders – the people of color bound and free – who helped build the Carolina that we cherish today.” This new memorial names no names, but honors those who labored to build the University. While not explicit, the table honors those who were enslaved prior to the Civil War. And it was dedicated two months after Moeser distanced the purpose of Memorial Hall from its original relationship with the Confederate Dead, expanding it to honor all those who have died in service.

Despite Moeser’s expansive spoken link between the Hall and veterans, the tablets did not change during this renovation. They were rearranged and spread throughout the building’s new additions, but there does not appear to have been a major campaign for additional tablets. It was another two years before additional UNC alumni who died in war were officially recognized by name, and this recognition did not take place inside the Hall itself.

“684 Noble Spirits”[46]

In 2002, the General Alumni Association’s Records Department began efforts to compile a list of all UNC alumni, staff, and faculty who died in conflict or in military training. Their project, much like the original effort to create a memorial for Swain and then for the Confederate Dead, was inspired and funded by alumni. Robert W. Eaves, UNC class of 1958, proposed the memorial after noticing that the campus landscape lacked a proper tribute to those killed in service. Five years later, the “List of Carolina Alumni Lost in Military Service” was installed and dedicated in an open area beside Memorial Hall.[47]

In 2002, the General Alumni Association’s Records Department began efforts to compile a list of all UNC alumni, staff, and faculty who died in conflict or in military training. Their project, much like the original effort to create a memorial for Swain and then for the Confederate Dead, was inspired and funded by alumni. Robert W. Eaves, UNC class of 1958, proposed the memorial after noticing that the campus landscape lacked a proper tribute to those killed in service. Five years later, the “List of Carolina Alumni Lost in Military Service” was installed and dedicated in an open area beside Memorial Hall.[47]

When first installed, the book included 684 names, but numerous names have since been added. The book is part of a larger memorial complex includes a stone bench and multiple concrete slabs in the walkway inscribed with quotations from soldiers’ reflections on their various wars. The book stands as the focal point of the space. Unlike the rest of the memorial, it is not intended to blend into the surroundings. It is not functional as a sidewalk or resting space. It is purely and exclusively a memorial, facing Memorial Hall, and, as described by William C. Friday in his dedication speech, “fitting sits in the heart of the campus of this great old University whose sons and daughters have been involved in every struggle when and where freedom was challenged around the world.” Friday’s dedication emphasized the patriotism, loyalty, and integrity of those honored by this memorial. The names inscribed in these bronze pages, and the names that would be added later, were presented as names of those for whom the University is and should be proud. They are the names of individuals who lived lives of service, and who dedicated themselves to the values and ideals that this University celebrates.[48]

It is unclear whether the memorial book holds an officially recognized relationship to the Hall, but the similarities between the two are undeniable. Both memorials were established on the request of alumni, and both were funded primarily by alumni. Perhaps more importantly, both Memorial Hall and the Book of Names memorial were created as living lists. Tablets were added to the walls of Memorial Hall for approximately eighty years after its first doors opened. The bronze book does not have pages that turn, but is filled with pages that slide in and out. The majority of the pages are engraved and bear the names of veterans who have died in service, including the names of the same Confederate soldiers who are listed inside of the neighboring Memorial Hall. Looking forward, the bronze book was created with blank pages, leaving room for the names of alumni who die in future conflicts. The Book of Names realizes the memorial mission outlined by Moeser: it is a space of remembrance for all who die in service to this country, and it is a memorial that will grow in perpetuity.

“History in Stone”[49]

On December 9, 1926, The Daily Tar Heel published the headline “Memorial Hall Tablets Bought to Help Defray Building Costs: Honor Roll Scheme Nets $10,000—Only Three Got in Free.” The essay that followed included the subtitle “History in Stone,” as the names and dates inscribed on the memorial tablets were, in fact, written in stone. But the purpose of these tablets and their significance has not maintained the same permanence as the artifacts themselves. The 1926 article asked, “Just what is the significance of all those tablets in Memorial Hall? This is a question too frequently asked among the student body, especially the new men each year.”[50] The answer to this question has changed as many times as the building itself, a living record of UNC’s noted dead.

Almost 100 years later, the Carolina community continues to negotiate the history of this memorial and the contemporary legacy of its ambiguous purpose. Ryan Griffin, a Carolina Performing Arts employee, sees Memorial Hall as an important site linking the University’s past to the present. It has long stood as a crucial space of University celebration, gathering, and entertainment. And it is a building filled with names, far more than those relegated to the tablets on the walls. The chairs in the auditorium are decorated with small metal plaques that bear the names of those who have donated to Carolina Performing Arts. The David Lowry Swain Society is an exclusive group of people who have all given $10,000 or more. But these additional names are not connected to the memorial purpose, at least not as it is understood by the student staff in the box office. When asked questions, Griffin explained, students are told to give guests a brochure and answer saying the building is filled with memorial tablets dedicated to people who were important to the University, to the State, and to the Civil War.[51]

The University, the State, and the Civil War. This understanding of Memorial Hall directly reflects the intentions outlined by Paul Cameron, the Alumni Association, and the Board of Trustees. Memorial Hall was to be a focal point of the campus landscape, and the primary space for honoring significant individuals. In the past 150 years, the landscape surrounding the Hall has changed and evolved. The architecture has become streamlined, filled with many additional buildings and memorials. In the 2000s alone, this Hall saw major reconstruction, and the campus memorial grounds were expanded to include the Book of Names, the Eve Carson Memorial Butterfly Bench, the 9/11 Memorial Garden, the Unsung Founders Memorial, and Memorial Grove. New names are no longer added to the walls of Memorial Hall, but the University continues to value physical commemoration. As the University maintains this historic memorial and the community establishes new spaces for honoring “notable North Carolinians,” there is increasing ambiguity around the intended rhetorical purpose of Memorial Hall, as evidenced in the division between the names on the tablets inside, and the names that fill UNC’s memorial landscape.

Unanswered Questions:

The history of Memorial Hall is far more vast and expansive than can be researched in one semester or represented on one website. From the start of my research, I was intrigued by two specific aspects of this hall: 1. That it was originally to be named Swain Memorial Hall, 2. That there is a Book of Names outside that expands upon the Confederate Dead listed inside. These two findings led me to explore the memorial purpose of this Hall, creating a lens that I enjoyed following, but one that left out many aspects of Memorial Hall, its origins, history, and use. To continue this research, I would further investigate the contemporary memorial landscape of UNC, looking deeply into Board of Trustee reports on the reopening in 2005, the creation of the Book of Names, and the dedication of the Unsung Founders Memorial. I personally have a hard time accepting that these memorials do not exist in conversation, and I am continuing to tease out what the conversation may be.

Beyond the scope of this essay, it would also be fascinating to explore the performances and events hosted in this venue. This stage has seen commencement ceremonies, minstrel shows, concerts, and lectures of great speakers ranging from Elie Wiesel to Bill Nye. I wonder if it is possible to trace the arc of American popular culture and performance art through the performances at this one site. And finally, this building is the site of many legends, morbid tales, and supernatural claims. The original architect didn’t even live to see his coffin-shaped structure completed. The 2005-2006 grand reopening season was advertised with pamphlets featuring Evan, the ghost who attended every performance. What is the relationship between the memorial purpose and the tendency to attach the spiritual and supernatural to this building?

These continued strands of exploration leave even more unmentioned and uncovered. My goal with this essay is to simply start conversations and encourage further research on this building that is central to UNC’s campus and history.

___________________________________________

Special thanks to Ryan Griffin, Interim Ticket Services Manager at Carolina Performing Arts, for showing me around Memorial Hall, answering my many questions, and directing me to a number of photographs included in this essay.

[1] Memorial Hall Inaugural Proceedings, Wednesday, June 3, 1885. (Raleigh, NC: E.M. Uzzell, 1885), 7.

[2] For more on Gerrard Hall: http://www.unc.edu/interactive-tour/gerrard-hall/; https://www.carolinaperformingarts.org/ros_venue/gerrard-hall/; http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/architecture/gerrard-hall-1822-1837-1/.

[3] Memorial Hall Inaugural Proceedings, Wednesday, June 3, 1885, 6.

[4] Ibid, 7.

[5] Kenneth Joel Zogry, “The Forgettable Memorial,” Carolina Alumni Review, January/February 2013, 39.

[6] Memorial Hall Inaugural Proceedings, Wednesday, June 3, 1885, 7.

[7] Zogry, “The Forgettable Memorial,” 42.

[8] Letter from Paul Cameron, September 21, 1883, Box 13, Folder 449, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[9] Letter from Paul Cameron, September 17, 1883, Box 13, Folder 449, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[10] Letter from Paul Cameron, September 28, 1883, Box 13, Folder 449, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Letter from W. L. Saunders, October 16, 1883, Box 13, Folder 451, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[13] Memorial Hall Inaugural Proceedings, Wednesday, June 3, 1885, 11.

[14] I have found multiple references to a “postal card,” a “card,” and to the “Plan for Commemorating the great men of the University.” It seems as though Battle and/or Cameron circulated a sort of fundraising pamphlet that explained Memorial Hall and asked for donations. My guess is that this card would mark the formal transition from “Swain Memorial Hall” to “Memorial Hall,” because the language in the letters in the archives changes as responses begin to come in at the start of 1884. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find any such card.

[15] Memorial Hall Inaugural Proceedings, Wednesday, June 3, 1885, 11.

[16] In 1913, the University did complete a building called Swain Hall. For more information visit: http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/names/david_lowry_swain_1801_1868_and_swain_hall/.

[17] Letter from Walter L. Steele, January 8, 1884, Box 13, Folder 457, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[18] Letter from C. M. Broadfoot, February 14, 1884, Box 13, Folder 460, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Letter from Mrs. L. O’B. Branch, January 18, 1884, Box 13, Folder 457, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[21] Kemp P. Battle, Professor Emeritus of History, History of the University of North Carolina: Volume II, From 1868-1912, (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1912) 317.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Notes from July 29, 1925, Box 37: Memorial Hall Tablets Committee 1925-1956, in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Robert Burton House Records #40019, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[24] “Doomsday For Memorial Hall,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), January 28, 1930. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67925685.

[25] Kenneth Joel Zogry wrote on the construction and destruction of the original Memorial Hall, in which he suggests that the aesthetics of the building were primary reason for the buildings destruction, which was encouraged but not solely based upon structural issues. Kenneth Joel Zogry, “The Forgettable Memorial,” Carolina Alumni Review, January/February 2013.

[26] Report from John H. Gregory, December 7, 1929, Box 47, Folder 1723, in the University of North Carolina Papers #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Let Memorial Hall Retain Its Distinctive Ugliness,” republished from Raleigh Times, The Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 19, 1927. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67920285.

[29] “Down with Memorial Hall!,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), October 31, 1929. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67925248.

[30] Ibid.

[31] R. W. Madry, “Elaborate Ceremonies to Mark Dedication of New Auditorium,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), October 11, 1931. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67937596.

[32] Joe A. Hewitt, “Louis Round Wilson Library: An Enduring Monument to Learning,” UNC Libraries, October 21, 2004. http://library.unc.edu/wilson/about/wilsonhistory/.

[33] Cynthia Mills, “Women in the Monumental Landscape,” Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, Accessed December 1, 2015. http://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/features/essays/mills/.

[34] See Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina: http://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/

[35] Letter from R. B. House, April 23, 1932. Box 2, Folder 83. in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Robert Burton House Records #40019, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[36] Ibid.

[37] “Memorial Hall,” undated, Box 2, Folder 83, in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Robert Burton House Records #40019, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[38] The names are: Kemp Plummer Battle, Edwin A. Alderman, Marvin Hendricks Stacy, J. Bryan Grimes, W. N. Everett, Richard H. Lewis, Edward Kidder Graham, Henry R. Bryan, and Kerr Craige. There is not a tablet for W. N. Everett, though there is a dormitory named for him. Ibid.

[39] “Memorial Hall (027),” Plan Room, Facilities Services: Engineering Information Services Plan Room, Accessed December 1, 2015. http://planroom.unc.edu/FacilityInfo.aspx?facilityID=027 .

[40] Letter dated February 7, 1949, Box 2, Folder 83. in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Robert Burton House Records #40019, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

[41] Letter dated August 28, 1929. Box 2, Folder 83. in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Robert Burton House Records #40019, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[42] Remarks at the Memorial Hall Dedication, September 8, 2005, Box 37, Folder 1596, in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: James Moeser Records #40228, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[43] The only exception to the rigidity of interpretation is the addition of a bronze plaque attached to the building as part of the gift of the Class of 1985. The plaque reads “Memorial Hall, Completed 1931, Memorial to David Lowrie Swain (1801-1868), President of the University (1835-1868), and to Alumni and Friends of the University.”

[44] Memorial Hall Transformation Campaign Committee Meeting, 21 September, 2001. Box 11, Folder 415, in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: James Moeser Records #40228, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[45] Remarks at the Memorial Hall Dedication, September 8, 2005, Box 37, Folder 1596, in the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: James Moeser Records #40228, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[46] William C. Friday, “Remarks of Memorial Dedication by William C. Friday: In Memory of Those Lost in Military Service,” Carolina Alumni Review, April 12, 2007. https://alumni.unc.edu/news/remarks-of-dedication-by-william-c-friday/.

[47] “In Memorial to Carolina’s War Dead,” Carolina Alumni Review, April 25, 2007. https://alumni.unc.edu/news/war-memorial-complete-list/

[48] William C. Friday, “Remarks of Memorial Dedication by William C. Friday: In Memory of Those Lost in Military Service,” Carolina Alumni Review, April 12, 2007. https://alumni.unc.edu/news/remarks-of-dedication-by-william-c-friday/.

[49] “Memorial Hall Tablets Bought to Help Defray Building Costs: Honor Roll Scheme Nets $10,000 – Only Three Got in Free,” The Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), December 9, 1926. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67920073.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ryan Griffin (Interim Ticket Services Manager, Carolina Performing Arts) in discussion with author, October 2015.

___________________________________________

[A] Carolyn A. Wallace, “David Lowry Swain, 4 Jan. 1801-29 Aug. 1868,” Documenting the American South, Accessed December 1, 2015. http://docsouth.unc.edu/browse/bios/pn0001638_bio.html; Brant & Fuller, “David Lowry Swain,” in Cyclopedia of eminent and representative men of the Carolinas of the nineteenth century, with a brief historical introduction on South Carolina by General Edward McCrady, and on North Carolina by Samuel A. Ashe. v.2, (Madison, Wis.: 1892), 204, PDF e-book.

[B] “North Carolina’s Richest Man,” The Charlotte News, America’s Historical Newspapers (Charlotte, NC), Jan. 6, 1891.; Brant & Fuller, “Paul Carrington Cameron” in Cyclopedia of eminent and representative men of the Carolinas of the nineteenth century, with a brief historical introduction on South Carolina by General Edward McCrady, and on North Carolina by Samuel A. Ashe. v.2, (Madison, Wis.: 1892), 347, PDF e-book.; Hope Summerell Chamberlain, Old Days in Chapel Hill, Being the Life and Letters of Cornelia Phillips Spencer (Chapel Hill; London: The University of North Carolina Press; Oxford University Press, 1926), 221, 222.; This information is located in a footnote that begins on the bottom of page 221 and ends on 222.