By Kaitlin Henderson

What is a building dedicated to science? How does one come to exist? What connections does it need to make, and what roles does it need to fulfill? The Morehead Planetarium, very much a university building dedicated to science, is an excellent case to offer a glimpse into some of the idiosyncratic answers to these questions.

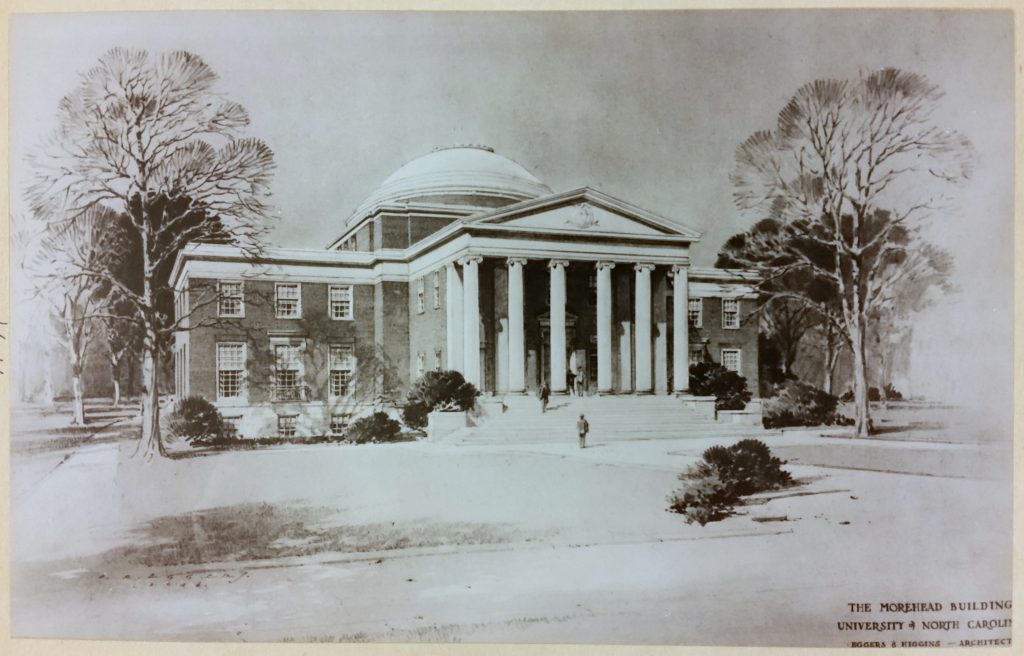

Morehead Planetarium, c. 1949, from the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

John Motley Morehead III was a prominent scientist and philanthropist who paid for and oversaw the design of the planetarium on UNC’s campus. His beliefs and motivations were shaped by his family and by scientific practices of his day, which in turn influenced the building he created. Those significant influences in turn have affected the evolution of the Planetarium since its opening to this day. Both the history of John Motley Morehead III and the Morehead Planetarium reflect changing views on the perceptions of various technologies and the important connections of science with religion, nationalism, and commercialism.

a timeline overview of major events with John Motley Morehead, III (in red & top row) and the Morehead Planetarium (in blue & middle row) through 2015

John Motley Morehead III

John Motley Morehead (I), undated, from “The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia”*

John Motley Morehead (the first with that name) was born in 1796 and led a life that was very involved in the state’s politics. The issues of educational and transportation infrastructure were important to him, and as governor he earned the moniker “Builder of modern North Carolina.”[1] James Turner Morehead, John Motley Morehead’s son, was born in 1840 in Greensboro and graduated from UNC in 1861. Among other activities, James ran his own manufacturing companies, one of which was the Willson Aluminum Company, an outreach of his mining interest. Mary, his wife, had a passion for education. Together, this family cultivated a sense of patriotic duty and entrepreneurial determination in the son of James and Mary, John Motley Morehead III (the name “Morehead” alone on this page will refer to John Motley Morehead III).[2]

Morehead was born in 1870 and attended UNC as part of the class of 1891. After graduating he went to work at his father’s Willson Aluminum Company. He was first in charge of overseeing the installation of a new manufacturing plant and then continued there conducting research as chief chemist. In 1892 he was one of those to discover a new, more efficient way of producing calcium carbide, which is used to make acetylene gas. Lucrative commercial applications were later discovered for acetylene, but when Motley and Willson Aluminum Company discovered their process there was no immediate market.[3]

John Turner Morehead standing, middle and Mrs. James Turner Morehead standing, second from right, undated, from “The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia”*

Morehead tried his hand at several manufacturing and power companies in New York and Pennsylvania overseeing production factories. By 1897 the acetylene industry, and with it the calcium carbide industry, seemed to have built up; Morehead moved to the American Calcium Carbide Interest that year as a construction engineer.[4]

John Motley Morehead, III, undated, from “The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia”*

In 1902 the American Calcium Carbide Interest was acquired by the People’s Gas Light & Coke Company in Chicago. Morehead followed the change in location and continued rising through the engineering ranks, collecting patents along the way. Notably, he oversaw plants that produced toluol, a key chemical used in the explosive TNT. The St Louis and San Francisco Expositions (in 1904 and 1915, respectively) recognized his prominence within the scientific and industrial community by asking him to serve on their International Jury of Awards. In 1915 he married Genevieve Margaret Birkhoff, from Chicago.[5]

When the US entered World War I in 1917 Morehead was commissioned as a Major in the US Army to install chemical manufacturing machinery. During the war he also served on several committees associated with the manufacture, control, and distribution of various chemicals used in explosives.[6]

Genevieve Margaret Birkhoff, undated, from “The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia”*

After the war Morehead was transferred to the Army’s Reserve Corps and continued his job at the now-named Carbide Corporation. He and Genevieve moved to Rye, New York, to be closer to the company’s headquarters in New York City. A few years later he followed the leads of his father and grandfather and entered the world of politics. He served as Rye’s mayor from 1925 to 1930, at which time President Herbert Hoover appointed him as a diplomat to Sweden. He lived in Stockholm during his service as envoy, from 1930 to 1933. In his second year there he was awarded the gold medal from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the first non-Swede to have such recognition. When his diplomatic position ended in 1933, he returned to his job at the Carbide Corporation and his home in Rye.[7]

After his time as mayor, Morehead also began his philanthropic track. In 1931 he presented UNC with the Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower, named for himself and his late cousin, Rufus Patterson.[8]

The Idea for a Planetarium

Morehead met with UNC president Frank Porter Graham in 1938 to begin discussing his next contribution. Over his life Morehead sought to cultivate his idea of the educated man, which he described as someone “who knows everything about something and something about everything… History, philosophy, law, economics, art, music and the classics, of course — but all of the natural sciences as well.”[9] That vision influenced his idea for this contribution. Genevieve died in 1945 and Morehead decided his next gift to the University would house his wife’s art collection along with encouraging interest in the natural sciences. Morehead was considering an observatory, with equipment for astronomical observations, or a planetarium to show audio-visual projections of astronomical images.[10]

According to some sources, a few years later Morehead met with Dr. Harlow Shapley, Director of Harvard’s Astronomical Observatory. Shapley had visited North Carolina earlier and famously called its citizens “the most astronomically ignorant people in all America.”[11] They discussed the options of an observatory or a planetarium. Reportedly, Shapley argued for the planetarium, which he saw as a way of educating a wide range of people on astronomy. He and Morehead supposedly made a deal that Shapley would amend his earlier condemnation of the state when Morehead built the planetarium. Another source questions this sequence of events, but either way, Shapley’s insult and later redaction have become a substantial piece of the building’s origin lore.[12]

In 1946 Morehead presented his proposal to UNC’s Board of Trustees. Governor Cherry thanked him for his “great and magnificent gift” and the Board unanimously accepted it.[13]

Morehead’s proposal for the Planetarium, February 11, 1946, from “Minutes”*

Governor Cherry (left) and Morehead (right) at the meeting of the University Board of Trustees meeting where he proposed the Planetarium, February 11, 1946, from “The Morehead Building: University of North Carolina”*

Religion was an important part of the Planetarium’s foundation. Morehead chose a psalm to be displayed above the Planetarium’s entrance: “The Heavens declare the glory of God and the firmament sheweth His handywork.”[14] By incorporating it into the Planetarium he projected an idea (which had been supported for several hundred years by this time) of the practice of the natural sciences as an act of worship. In this partnership, religion would be intertwined with the accuracy and technological prowess of science — better science is a better appreciation of God’s work, and better science means better equipment and results.

In 1954 the Morehead Foundation published a book on the building’s history. In it, the Foundation proclaimed visitors would “lift up their eyes to the Heavens and spend an hour in the noblest aspiration of man’s mind: the understanding of the Universe.”[15] This planetarium would be the epitome of public science education – it would attract visitors, who would excitedly engage in learning through entertainment, and it would teach them about a fundamental concern not only of science, but of humanity. The Foundation’s language expressing this vision also evoked the religious connection with astronomical science.

architectural print of the Morehead Planetarium by Eggers & Higgins, c. 1947, from the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

The building itself had to be exceptional to line up with Morehead’s aspirations. It was designed by the architects Eggers and Higgens, who also famously designed the Jefferson Memorial and other buildings around the world. The materials and decorations were meant to inspire a weighty dignity. The projector would be a state-of-the-art Zeiss Model II. Morehead used his former diplomatic connections to travel to Sweden and purchase one there.[16] Though the decision over the Planetarium’s location is not much discussed in the written record, it is a very large, visible building at the face of the University on Franklin Street. Morehead initially estimated it would cost $1 million to build; before construction had even started, the sum jumped to $2 million, and it ended up being around $3 million. He created the John Motley Morehead Foundation simultaneously with his proposal for the Planetarium, which would fund the Planetarium’s construction. Any money left would go towards a new scholarship fund.[17]

Expanding Roles

The opening of Morehead Planetarium on May 10, 1949 was a big event. Morehead, Gunnar Dryselius (Swedish Consul to the US), UNC Chancellor Robert House, and North Carolina Governor Kerr Scott spoke. Graham, who was at this point U.S. Senator, gave the main address, expressing his belief that the Planetarium would “become a part of a great intellectual and spiritual center whose influence will reach across all the states through all the generations to come.” NBC broadcast it on their radio stations. The Daily Tar Heel published a special Planetarium Supplement.[18]

Graham’s speech at the opening of Morehead Planetarium, May 10, 1949, from “Following is the address of United States Senator Frank P. Graham…”*

Morehead with the Zeiss Model II projector, c. 1949, from the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

As Morehead intended, the building contained more than just the planetarium room. A Daily Tar Heel article walked readers through its many areas: the entry rotunda with paintings, a clock, and a barometer; a dining room and roof terrace; meeting rooms and a lounge; exhibit rooms devoted to a Copernican orrery (a moving model of the solar system through Saturn), the solar system, and larger astronomical features.[19] Clearly, it was meant to perform many functions for many audiences. The planetarium room was the centerpiece but it also engaged visitors with other content — traditional Western art and larger historical natural scientific processes — and facilities for varying uses. The Planetarium was not meant to be just a place of scientific study; it was more closely meant to replicate Morehead’s interests and vision of the educated man.

Genevieve B. Morehead Rotunda, c. 1960, from the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

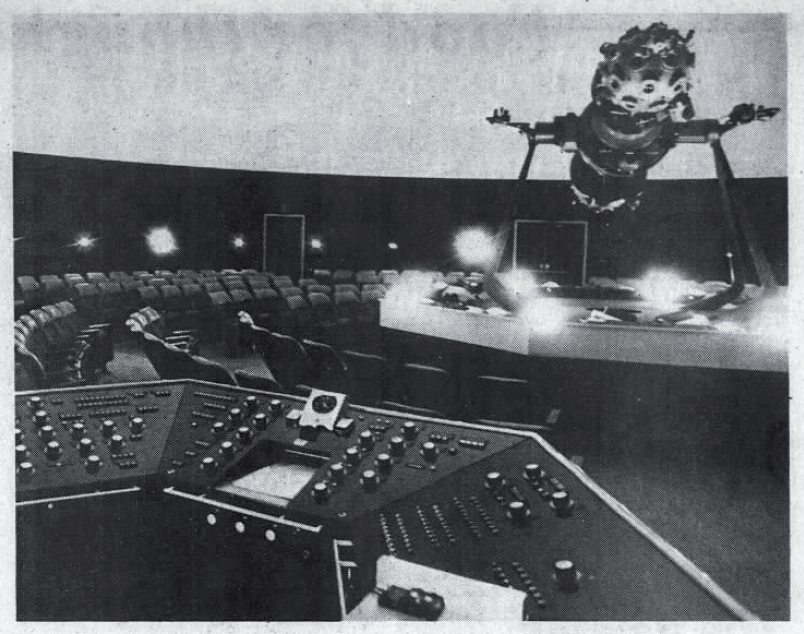

Roy Marshall, the Planetarium’s first director, declared: “We can do here anything worthwhile done at any planetarium, and we can do it better!”[20] After all, this was the newest, most advanced planetarium in the world. Marshall had previously worked at the Alder Planetarium in Chicago and then the Yerkes Observatory at the University of Chicago. He emphasized how important the Planetarium was as an educational mode, saying “we’re going to make it pleasant for laymen to learn things they would turn their noses up at if it were offered to them in dry lecture form.”[21] He also described the transcendence that occurs between the cold technicality of the equipment and the resultant “beautiful work of art.”[22] A planetarium show was effective because it was a wholly convincing, transformative experience.

Christianity remained an important connection in the Planetarium’s operation, too. Some of the early shows had names that evoked religion: “Let There Be Light,” “Eastre,” “Star of Bethlehem.” Morehead visited the Planetarium in the fall of 1949 to inspect Marshall’s Christmas show and told the Daily Tar Heel: “Now for the first time… I know that I’ve got my money’s worth with that planetarium down in Chapel Hill.”[23] Marshall’s narration of the show was radio broadcast across the state on Christmas day.[24]

The student government invited all of the North Carolina ministers they could contact to a special showing. Although the interest was less than ideal (350 showed up), the event followed the thread of the fundamental connection between the stars and Christianity.[25] While not all of the state’s ministers were interested in such a practice, clearly a select few and the students who came up with the idea were.

Morehead Planetarium Sundial, 1956, from the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

Morehead, meanwhile, continued his work with Union Carbide and expanded his philanthropy. He donated a stadium and chimes to his hometown high school and returned with a new gift for the University in 1956. At this time, he funded the construction of the sundial that sits in front of the building. Graham again gave the opening address, and emphasized the interdisciplinarity of constructing such an object – it “requires use of astronomy, geometry, logarithms, geography, mechanics, architecture and the fine arts.” In other words, it’s another gift that epitomized Morehead’s educated man. The sundial was also state-of-the-art, accurate and tied to complex contemporary science. And of course, Graham noted Morehead’s “abiding devotion” to UNC in providing it.[26]

Modern Developments

Throughout his life, Morehead and those who wrote about him emphasized his capabilities as an “educated man.” Biographies, such as that published by the Board of Trustees of his scholarship program, tend to begin with a list of his many accomplishments as signs of merit and greatness.[27]

In 1959 the NC General Assembly named Morehead “a lifetime, honorary member of the Board of Trustees.” Their resolution cited his dedication to the state and University, particularly through his gifts. This included the Planetarium, which they describe was “bringing the meaning of the stars of God’s heaven down to the people of North Carolina.”[28] The connection between astronomy and Christianity was not just for theologians or researchers.

resolution naming Morehead “a lifetime, honorary member of the Board of Trustees,” April 10, 1959, from “A joint resolution…”*

A year later, the UNC student legislature declared November 3rd to be “John Motley Morehead Day.” They honored him to recognize his various contributions to the University, including the Planetarium. A Daily Tar Heel article called Morehead “one of the University’s greatest benefactors” and remarked that the day would be celebrated with “the bells in the Morehead-Patterson bell tower… played six times today to remind the campus of Morehead.”[29]

Morehead died in 1965.[30]

![Jenzano (left) and Marshall [?] (right) with the Zeiss Model II projector, c. 1949](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2015/11/2015-11-04-16.44.56-copy-1024x869.jpg)

Jenzano (left) and Marshall [?] (right) with the Zeiss Model II projector, c. 1949, from the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

With this personal connection to the events happening at NASA, UNC and North Carolina more generally followed the space race closely. Articles in the Daily Tar Heel covering progress in space flight often mentioned when the astronauts had been on campus. When three astronauts were killed in a plane crash in 1966, a student wrote a personal and heartfelt tribute to one of them. After the astronauts travelling on Apollo 11 became the first men on the moon, another student wrote a history of their time training at the Planetarium.[33] The astronaut training was a point of nationalistic pride for the Planetarium and the University.

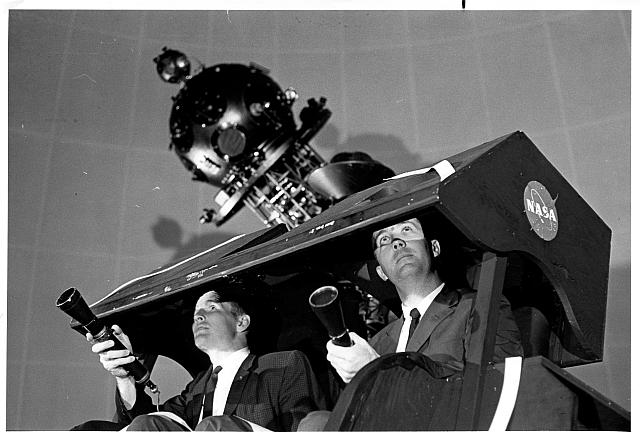

(left-right) Col. Gordon Kage (UNC AFROTC), M.S. Carpenter (astronaut), Walter Schirra (astronaut), Dr. James W. Batten (Planetarium staff), 1960, from the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

In 1959, Morehead gave a new $25,000 gift for a projector upgrade. Although there hadn’t been much grumbling about the original projector being out of date, it seems the pressure to have state-of-the-art technology that came with astronaut training led to an earlier replacement schedule than might have otherwise occurred. Plus, the new device came with new technical abilities. The lighting source would be brighter, able to better show motion and enlargement, and more efficient; it would have methods for showing eclipses, comets, and the solar system built in; and would have variable speed motors and a special extra projector. These missing capabilities weren’t much bemoaned earlier — technicians had improvised their own methods for showing eclipses, but things like “the change of brightness in planets that occur in nature” were simply ignored.[34] The standards for precise representation shifted with changing technological capabilities; it wasn’t that Planetarium technicians didn’t know planets’ brightnesses varied, but it was irrelevant for imagery. The new Zeiss Model VI, purchased with Morehead’s 1959 funding, was installed in 1968. With the new lens, Jenzano called Morehead Planetarium “the most modern and best equipped in the world.”[35]

Astronauts Ed White and Jim McDivitt training in the Planetarium, 1963-1966, from the NASA Langley Cultural Resources and Archives

Jenzano explained the Planetarium’s central purpose to a Daily Tar Heel writer in 1970: “The planetarium is an educational vehicle to convey to the lay public what is learned in the research laboratories and observatories.”[36] In contrast to the Planetarium’s early period, the emphasis had shifted – or rather split – away from appealing to anyone and everyone. By this point, there were separate programs for experts in the field, like the astronauts, and the general public. Additionally, the point of the programs at this time was to convey the current state of astronomical knowledge. Planetariums were no longer novel, they weren’t there to induce wonder at the scale of the universe. The connection to Christianity had also fallen into the background, replaced by a nationalistic connection to the space race.

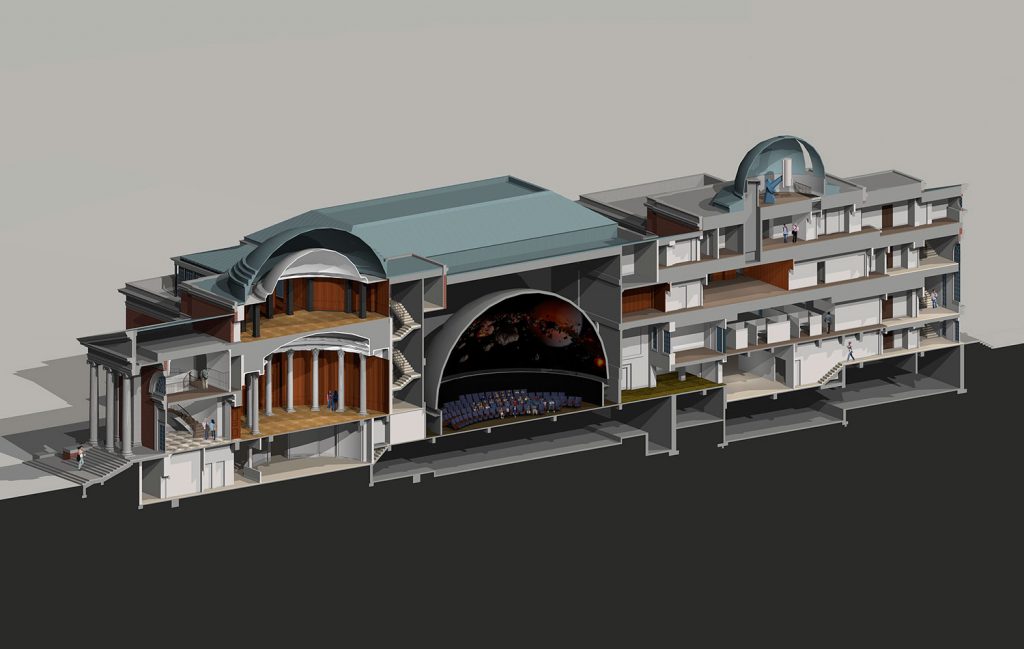

Additionally, the Planetarium expanded its science education scope beyond projected shows. Morehead had originally debated whether a planetarium or observatory would serve his goals better. However in 1973 the Planetarium apparently decided there was no longstanding reason it needed to stick with that choice of one over the other. The Morehead Foundation provided for a large addition to the east end of the Planetarium building, notably containing an observatory and astronomy labs. The observatory is still used today, although the Department of Physics and Astronomy refers to it mostly as a teaching and training telescope. This seems to be due to its location in Chapel Hill more than the technological currency of the equipment itself. The nature of contemporary astronomical research means that the department uses observatories in more suitable locations like Chile and Arizona for their research data, while the Morehead observatory offers student experience with equipment. More in line with the original goals of Morehead’s building, it also hosts regular public presentations by faculty or graduate students where the audience can use the telescope themselves as an interactive illustration of the presentation.[37] In both of these aspects, the observatory addition provides a new way for the Planetarium to educate the general public and specialists.

architectural cross-section of the Planetarium (left) with east wing addition (right), from Hartman-Cox Architects

Morehead Planetarium with the east wing addition (left), undated (post-1973), from the Morehead Planetarium & Science Center

Precarious Adaptations

In 1981, after 30 years as director, Jenzano resigned. By this time, a Daily Tar Heel article remarked that “the number of planetariums in the Western Hemisphere has grown… to more than 1,200.”[38] They were commonplace and there was a mismatch between the Planetarium’s offerings and the public’s desires and expectations, which could be read in the declining ticket profits. A Daily Tar Heel writer reviewed a show in 1982, saying: “despite the technological frufru, the show is a little cheesy. The story is a little corny, stars peek through ostensibly solid buildings and planets, and the spaceships don’t really look like they’re flying.”[39] Viewers weren’t as interested in a dramatic action show that was also trying to teach them about science when they could see more cohesive effects and narratives at the movies. Public expectations for accurate scientific content and special-effects entertainment diverged in other media which emphasized one over the other; the Planetarium found itself caught.

Tony Jenzano, 1980, from the Daily Tar Heel

Morehead Planetarium tried various tactics to update its appeal. In 1983, under new director Lee Shapiro, the Planetarium presented “Laser Floyd,” a live laser show choreographed to Pink Floyd music. Those creating the Planetarium shows continued to weave in pop culture elements: one in 1982 was narrated by William Shatner and in 1989 there was a Saturday morning children’s show called “Winnie-the-Pooh and the Golden Rocket.” With these and other shows, Shapiro declared in 1987 that the Planetarium had become “much more media-oriented,” containing extra “projectors for slides and special effects” and “facilities to show special films on a 180-degree semi-panoramic screen.”[40] Planetarium staff attempted to outmaneuver the successful special effects technology in movies by stepping up their unique technological capabilities.

Even the language framing what the Planetarium did shifted: “shows” were now “presentations.” The new word connoted a more information-based mode, as opposed to entertainment. In a related move, presentation creators also began looking to the past for content. A program called “Legacy” in 1989 looked back on Apollo 11 and the space race.[41] Shapiro and those creating the presentations were also appealing to the academic side of their potential audience. Rather than choosing a side — entertainment or academia — the Planetarium tried to bridge the widening gap.

At the same time, the Planetarium saw an outside expansion of its functions. In 1989 the first Campus Visitors’ Center, funded by a gift from the Class of 1984, opened in the Morehead Building’s west entrance lobby.[42] Presumably, this was a mutually beneficial arrangement. The Planetarium would receive visitors who may have come to campus for other reasons, in a space they may not have fully needed anymore since their addition a decade earlier. Meanwhile, the new Visitors’ Center could be located at the front entrance to campus, in a building that already functioned as a gateway between the general public and campus academics.

the UNC Visitors’ Center at the Planetarium’s west entrance, undated (post-1985), from the UNC Visitors’ Center

Despite these efforts, however, he Planetarium struggled to regain the immense public interest it once enjoyed. A UNC student wrote a letter to the Daily Tar Heel’s editor in 1992 deploring the “harsh criticism” of a presentation and general lack of interest in the “great (and inexpensive!!) entertainment” at the Planetarium.[43] The attempt to bridge bifurcated audience expectations for entertainment and accurate scientific content wasn’t entirely working, partly due to the aging technology.

Rapid progression and the associated turnover had always been a part of science, especially in the equipment-focused technology and manufacturing fields. The Planetarium’s projector system was no exception. In 1982, the new projector was still perceived by visitors as a “state-of-the-art gizmo” but Planetarium staff acted otherwise.[44] In that same year the projector began getting computerized upgrades, a process that was completed in 1985. The goal was to separate the creation of a show from its performance: “the artistic planning of a show would be done ahead of time, and the computer would run the show itself.”[45]

the Planetarium room in 1981, from the Daily Tar Heel

During this time the Planetarium’s fluid religious ties also came to the forefront, in a controversy over the separation of church and state. Since the 1960s the Planetarium had advertised its annual Christmas show with a star decoration. In 1982 a UNC law professor, Barry Nakell, questioned whether that was appropriate. The Planetarium removed the star after Chancellor Fordham requested it be taking down “rather than offend any particular segment of the community.”[46] Two years later it returned, with Shapiro supporting its ability to act as symbol not exclusive to Christianity. To that end, the star was also used to advertise a program focused on astronomy in Chapel Hill the following May.[47]

The Planetarium Today

2009 reprise of “Laser Zeppelin,” from the Daily Tarheel

Holden Thorp, chemist and UNC professor, took the Planetarium’s directorship from 2001 to 2004. He focused on making it, as a coworker put it, “a place that was vital and relevant again.”[48] He brought in exhibitions from other sciences to the renamed “Morehead Planetarium and Science Center.” The Planetarium applied for and received a $1 million grant from NASA to underwrite at change, which would include “an enhanced discovery center with exhibits from University research, an interactive, Web-based center; and several mobile units, which will travel throughout North Carolina to bring the Morehead Center to students and teachers across the state.” The Planetarium took on a much expanded role outside its dome. The building itself, at this point derided as either having “some wear and tear” or being “an embarrassment,” began an upgrade in line with the larger overhaul.[49]

Jarrod Jenzano (grandson of Tony Jenzano, left) and Gabi Tesoro (granddaughter of Richard Knapp, former astronaut educator, right) at the dedication of the NC Highway Historical Marker for Astronaut Training at the Planetarium, 2015, from the Daily Tarheel

Todd Boyette, with a substantial background in science education, became director after Thorp and oversaw the end of the Science Center upgrade. By this time, the computer-enhanced projector was no longer able to efficiently fulfill the Planetarium’s needs. An article at the Daily Tar Heel described the Zeiss VI as “clunky and obtrusive” and derided the fact that it “required 300 or 400 additional pieces of equipment working together for multimedia presentations,” these additional pieces the very ones that were added to make it more modern in 1985.[50] Another article explained that “the Zeiss Model VI Star Projector is a community legacy, and its death is imminent.”[51] Boyette framed it slightly differently: it was a liability, since it would be difficult to fix it if it broke. He explained that “there was no choice.” In place of its earlier position as top-notch, awe-inspiring technology, the Zeiss VI had become so out of date as to be nostalgic. The Planetarium had tentative plans to display it as an exhibit piece, with one staff member saying “it will remain dear to people’s hearts.”[52] Staff and visitors still admired the technology, but since it was no longer performing the function it was designed to that celebration was transferred to its history.

The Planetarium’s marketing manager (another new role added in recent years) called the new digital projector, installed in 2010, “the biggest technological advance we’ve had, possibly in the planetarium’s history.” The technology was revolutionizing the Planetarium, at least for those on the inside. It seems, however the Morehead Foundation was no longer willing or able to foot the bill for a major equipment upgrade as they had in the past, and the Planetarium sought out corporate sponsorship. GlaxoSmithKline provided the $1.5 million necessary to buy and install the new digital projector, in exchange for naming the area after them.[53] In a neat connection with the Planetarium’s origins, commercial research and development was once again funding public science education.

Boyette’s idea of the Planetarium’s mission was a kind of revamped version of the original goal of showing a wide audience the possibilities of science. Like the early Planetarium directors, he noted, “it’s a great way to learn science basics because it presents it in a fun and entertaining environment.” He emphasized that this kind of engagement was for everyone, from “rural students who might not be aware of the possibilities of a college education” to those who might already be familiar with astronomy. Boyette saw the Planetarium’s mode of education as ideal in that its “interactive activities and multimedia presentations… will leave a lasting impression.”[54] Although the methodology and content focus were different, his vision really hearkens back to Marshall’s. Importantly, though, it lacks the pointed emphasis on scientific precision; it’s not that precision isn’t important, but rather that it’s now a background consideration.

a video highlighting some of the considerations when making a show in 2012, from the Planetarium’s When in Dome blog

Closing thoughts

Morehead’s Planetarium has lived on a somewhat astronomical scale, above numerous smaller-scale rises and falls. Projector systems were at the peak of humanity’s technological capabilities and then fell dramatically to their nadir. Science was an important aspect of Christianity, then nationalism. The point of a planetarium was to entertain the public while covertly educating them; to inspire people to enter scientific careers; to patriotically answer the nation’s scientific needs; to entice segmented audiences into engaging with astronomy; to connect with history.

Somewhat surprisingly, this incredibly specific space has been versatile over the years. A planetarium is an odd, precisely defined room; it’s not good for much else. Morehead Planetarium has adapted its mission and complementary spaces around that enduring space. Its flexibility and responsiveness come, at least in part, out of Morehead’s original idea for the Planetarium. As a space for cultivating his “educated man” — knowing something about everything and everything about something — nothing was out of scope. Astronomy provided the foundation for its content but any connection could be incorporated. Visual arts, contemporary music, religion, popular movies, and more all fit in Morehead’s original expansive vision. Importantly, these connections not only fit in but were central to its mission. The Planetarium is a public space for broad engagement, and it has survived over the decades by adaptively growing its programming in accordance with the public’s interest.

This is only an opening look at the Morehead Planetarium’s history, following the threads of science as it relates to religion, nationalism, and commercialism. None of these individual threads are complete, let alone the full history of the Planetarium and its benefactor, John Motley Morehead III. Personally, I would love to delve more deeply into the ebb & flow and transformations in the associations of Morehead and the Planetarium with Christianity and science. What exactly did Morehead himself think about Christianity? How was it related to his view of an “educated man” or the commercial practice of science? How else did Christianity, indirectly or explicitly, play into the programming and development of the Planetarium over the years? I’ve tried to start looking at these questions in this narrative, but they’re far from answered.

_______________

[1] The John Motley Morehead Foundation [?], The Morehead Building: University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: The John Motley Morehead Foundation, 1954 [?]), np.

[2] John Motley Morehead [III], The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia (New York: the DeVinne Press [priv. print], 1921), 54-58 & 72-73.

[3] Morehead, The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia, 73; The Trustees of The John Motley Morehead Foundation, John M. Morehead: A Biographical Sketch (Chapel Hill: The John Motley Morehead Foundation, 1954), np.

[4] The Trustees of The John Motley Morehead Foundation, John M. Morehead, np.

[5] The Trustees of The John Motley Morehead Foundation, John M. Morehead, np; Morehead, The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia, 74-75.

[6] Morehead, The Morehead Family of North Carolina and Virginia, 74.

[7] “John Motley Morehead III: Ten Facts from a Remarkable Life,” UNC University Libraries, last modified November 25, 2014, http://blogs.lib.unc.edu/uarms/index.php/2014/11/john-motley-morehead-iii-ten-facts-from-a-remarkable-life/.

[8] The Trustees of The John Motley Morehead Foundation, John M. Morehead, np.

[9] The John Motley Morehead Foundation [?], The Morehead Building, np.

[10] “History,” Morehead Planetarium & Science Center, accessed October 6, 2015, http://moreheadplanetarium.org/about/history; “Morehead, John Motley, III,” NCpedia, last modified January 1, 1991, http://ncpedia.org/biography/morehead-john-motley-iii; The John Motley Morehead Foundation [?], The Morehead Building, np.

[11] “History,” Morehead Planetarium & Science Center.

[12] The John Motley Morehead Foundation [?], The Morehead Building, np; “History,” Morehead Planetarium & Science Center; Louise Gunter, “Morehead Planetarium,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), October 23, 1980.

[13] Minutes, February 11, 1946, Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina (System) Records, 1932-1972, Collection Number 40002, Volume 3, University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 192-200.

[14] The John Motley Morehead Foundation [?], The Morehead Building, np.

[15] Ibid.

[16] The John Motley Morehead Foundation [?], The Morehead Building, np; Bill Kellam, “No Sleep For Weary As Planeteers Head Back To Morehead Job,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 23, 1948; Herb Nachman, “Planetarium Arranged Like Ordinary Theater,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), February 16, 1949; “History,” Morehead Planetarium & Science Center.

[17] Minutes, February 11, 1946, Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina, 193; “Morehead Planetarium Work May Begin Before End Of Term,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 3, 1947; Don Maynard, “Planetarium’s Young Life Is Filled With Adventure,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 10, 1949; The Trustees of The John Motley Morehead Foundation, John M. Morehead, np.

[18] “NBC To Carry Planetarium Story Monday,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 8, 1949; Frank P. Graham, “Following is the address of United States Senator Frank P. Graham, former president of the University of North Carolina, at exercises to be held at the University Tuesday afternoon at 3 o’clock when the Morehead Building will be dedicated,” Addresses and Reports of Frank Porter Graham, 1929-1949, Issued by University News Bureau and Others, May 10, 1949; “Planetarium Supplement,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 10, 1949.

[19] Herb Nachman, “Planetarium To Feature Rotunda, Star Exhibits,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), February 18, 1949.

[20] “Marshall Knows Stars; Will Make Study Easy,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 10, 1949.

[21] “Planetarium Will Be Run By Marshall,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), February 17, 1949; “Marshall Knows Stars…,” The Daily Tar Heel.

[22] Dr. Roy K. Marshall, “Planetarium Is Thing of Beauty, Not Observatory,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 10, 1949.

[23] “Christmas Here Soon For Planetarium Staff,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), October 6, 1949.

[24] “Anniversary Program To Begin At Morehead,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), April 30, 1950; “Planetarium Show Is Story Of Easter,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), March 21, 1951; “Christmas Here Soon For Planetarium Staff,” The Daily Tar Heel; “Radio Group Will Present ‘Star’ Show,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), November 16, 1949.

[25] “Morehead Planetarium Work May Begin Before End Of Term,” The Daily Tar Heel; “N.C. Preachers Tour Morehead,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 13, 1949.

[26] The Trustees of The John Motley Morehead Foundation, John M. Morehead, np; Frank P. Graham, “The sundial, man’s first keeper of time, a present precious possession of the university, given by John Motley Morehead,” The Chapel Hill Weekly (Chapel Hill, NC), Friday, June 8, 1856.

[27] The Trustees of The John Motley Morehead Foundation, John M. Morehead, np.

[28] General Assembly of North Carolina, “A joint resolution providing for the election of John Motley Morehead as an honorary life-time member of the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina,” Raleigh: Generally Assembly of North Carolina, 1959.

[29] “Legislature Declares Today ‘John Motley Morehead Day’,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), November 3, 1960; “Students Express thanks To Alumnus For Gifts,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), November 3, 1960.

[30] “John Motley Morehead III (1870-1965) and Morehead Planetarium,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History.

[31] “Planetarium Holds Quiet Anniversary,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 11, 1951; Maynard, “Planetarium’s Young Life Is Filled With Adventure,” The Daily Tar Heel; “Students Get New Cut Rate At Morehead,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), April 18, 1951; “History,” Morehead Planetarium & Science Center; Sidney Stapleton, “NASA & NC: the story of North Carolina’s important contributions to the United States space program,” Wachovia, July-August 1971, 13.

[32] “History,” Morehead Planetarium & Science Center.

[33] Ernest H. Robl, “Astronauts’ Dreams End Too Soon,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), January 31, 1966; Tom Marshall, “Planetarium Trains Moon Astronauts,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), July 10, 1969.

[34] “Students Express thanks To Alumnus For Gifts,” The Daily Tar Heel; “Coming: One New Planet Projector,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), September 17, 1966.

[35] “Coming: One New Planet Projector,” The Daily Tar Heel; “Planetarium Most Modern In The World,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), August 11, 1966.

[36] Evans Witt, “Planetarium Offers Educational Experience,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), October 2, 1970.

[37] Rachael Long, Building Notes, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill: Facilities Planning and Design, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1993), 390; “UNC Obseravtories,” Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, accessed November 14, 2015, http://physics.unc.edu/research-pages/astronomy-and-astrophysics/unc-observatories/; “Morehead Observatory Guest Night,” Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, accessed November 14, 2015, http://physics.unc.edu/seminars/morehead/.

[38] Randy Walker, “Jenzano resigns,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), July 9, 1981.

[39] David McHugh, “Morehead Planetarium presentations draw serious and amateur astronomers,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), September 14, 1982.

[40] David Schmidt, “Laser show at Morehead features Pink Floyd music,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), April 1, 1983; McHugh, “Morehead Planetarium…,” The Daily Tar Heel; Elizabeth Murray, “Man’s space flight history highlights Planetarium lineup,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 25, 1989; Hannah Drum, “An astronomical achievement,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), September 28, 1987.

[41] Elizabeth Murray, “Man’s space flight…,” The Daily Tar Heel.

[42] “Aliases and Notes for Morehead Planetarium (152),” Plan Room, Facilities Services Engineering Information Services, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, accessed October 6, 2015, http://planroom.unc.edu/index.aspx.

[43] Michael Neece, “Shows at Morehead not appreciated by community,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), February 17, 1992.

[44] McHugh, “Morehead Planetarium…,” The Daily Tar Heel.

[45] Guy Lucas, “Planetarium will close temporarily in January,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), October 8, 1984.

[46] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill: A History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 320.

[47] Guy Lucas, “Planetarium star returns home,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), December 4, 1984; Snider, Light on the Hill, 321.

[48] Brian Austin, “Thorp created new vision for planetarium,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 22, 2008.

[49] Austin, “Thorp created new vision for planetarium,” The Daily Tar Heel; Emily Drum, “Planetarium Might Get NASA Grant,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), July 6, 2001; Erin Zureick, “Planetarium to get a face-lift,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), August 23, 2006.

[50] “Leadership,” Morehead Planetarium & Science Center, accessed October 6, 2015, http://moreheadplanetarium.org/about/leadership; Zureick, “Planetarium to get a face-lift,” The Daily Tar Heel; Andrew Harrell, “Upgraded Planetarium to open in February,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), January 27, 2010.

[51] Jessica Kennedy, “Morehead Planetarium phases in new digital projector system,” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), April 25, 2011.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Andrew Harrell, “Upgraded Planetarium…,” The Daily Tar Heel.

[54] Zureick, “Planetarium to get a face-lift,” The Daily Tar Heel.