“Dean Carmichael! What do I do?! There are women outside raking my yard, and they want to come inside to use the bathroom!” Dean Carmichael responds, chuckling, “Why let them in to use the restroom of course!” “But… you have a rule against that!”[1]

In the 1960s, under Dean Carmichael’s tenure, the so-called “apartment rule” was a hot issue for many at Chapel Hill.[2] Katherine Kennedy Carmichael was an enforcer of rules, but not an overly unfair one. During her tenure as Dean of Women at UNC, which lasted from 1946 to 1972, Dean Carmichael fought for advancements for women on campus but also opposed many rule changes aimed at expanding women’s privileges on campus.[3] The legacy she left behind at Chapel Hill is one of positive changes for women – she wanted the women of UNC to realize their full potential through education.

In celebration of the impact that Katherine Kennedy Carmichael had on UNC, and of past, present, and future UNC women, the newly constructed Carmichael Residence Hall was dedicated in November of 1986. The ceremony lasted three days with several prominent speakers, as well as many events celebrating the achievements of women on campus.[4] The six story building was designed to house 486 undergraduate men and women – a much needed addition to on-campus housing given the increase in enrollment, especially women, throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[5]

A Closer Look – Life and the Personal Side

Katherine Kennedy Carmichael, born in 1912 in Alabama, graduated from Birmingham-Southern College in 1932 as an English major. She received a PhD from Vanderbilt University and was a post-doctorate research fellow at Yale University. She pursued a career in teaching, working at public schools in Alabama, Texas State College for Women, Western Maryland College, and Hockaday Junior College. She was also a Fulbright lecturer at Philippine Normal College, and a Smith-Mundt professor at the University of Saigon.[6] At UNC, she was held in high regard, receiving the Distinguished Service Award for Women in 1977 from the Chi Omega Fraternity.

Katherine Kennedy Carmichael (1912-1982). [33]

Dean Carmichael was also known for her good sense of humor, a sentiment derived from several personal anecdotes about the Dean. Funnily enough, the man who called Dean Carmichael’s office frantically asking about letting women into his house to use the bathroom, was none other than Joel Fleishman, who would go on to found the Sanford School of Public Policy and serve as vice president at Duke University.[8] A final anecdote, given by Pamela Dean, describes a hot fall day at UNC in the late 1940s. A small line of fraternity pledges snakes down the steps of South Building. Atop the steps stands Dean Carmichael, dressed in her usual business attire. But the proceedings are not very business-like – apparently Dean Carmichael stood patiently at South Building, allowing each fraternity pledge to complete a small initiation requirement – kiss the Dean of Women on the steps of the South Building! Carmichael waited patiently, and with the Southern charm she possessed, she gravely thanked each pledge after the kiss was planted.[9]

Women at UNC

Alderman and McRea – the Beginning

Mary McRea with Tar Heel staff, 1898. [34]

For context, in the United States, the first bachelor’s degrees earned by women were obtained from Oberlin College in Ohion in 1841. Other private colleges, such as Cornell University and the University of Michigan, both began admitting female students in 1870. In terms of public and state-funded institutions, the University of Iowa was the first university to become coeducational in 1855. The University of North Carolina, perhaps because of it’s location in the South, was delayed in implementing coeducation (especially compared to many institutions West of the Mississippi). It was not until almost the end of the 19th century that UNC finally began admitting female students, Other Southern Universities were also late in implementing coeducation, such as the University of South Carolina (1985), the University of Alabama (1893), and University of Tennessee (1893).

An early account of some difficulties faced by women at UNC is that of Mary Graves, a female student in 1906. She reflects upon the scrutiny that women dealt with, saying that they were constantly facing “a gauntlet of critical eyes.” Women in these early years had to dress and act carefully, doing their best to get in and out of class unnoticed. Graves recounts another occurrence, apparently all too common, “You would start toward an empty seat on the end of a bench and by the time you got there the whole row is vacant.”[11]

Drawing of early female student from the Yackety Yack, 1907. [35]

UNC Women’s University Club, 1906. [36]

The Fight For Housing

Things began to change when Inez Koonce Stacy, widow of Dean Marvin Hendrix Stacy, was appointed to the position of Women’s Advisor. Stacy immediately took on the role, advocating for more housing for women on campus.[12] She argued that women were scattered across campus, without centralized living or meeting spaces. Eventually, two buildings were provided to house 45 of the 65 enrolled women, but Stacy and the female students saw the accommodations as highly inadequate – the buildings were small (initially having served as slave quarters), cramped, and had no heat.

Coeds in dormitory, 1948. [37]

Almost 50 years after that fateful day in 1897 when Mary McRea agreed to enroll as the first female at UNC (persuaded by Edwin Alderman), Katherine Kennedy Carmichael came on the scene. In 1946, Carmichael became the Dean of Women, and received an adjunct appointment as a lecturer in the English Department. The first several years of her tenure were relatively quiet; she spent much of her time working with the Women’s Counsel overseeing the rules that governed everyday life for women on campus. She also continued to advocate for better and safer housing for women. A review of both the Men’s Council and Women’s Council found that in 1952, many more women were reprimanded than men, despite there being more men enrolled. Dean Carmichael worked with the Women’s Council to rectify the stiff governance over women, and she resisted multiple attempts by the university to integrate the separate men and women’s student government. Through her experiences with the Women’s Council, Carmichael watched as young women stepped into student government roles, gaining crucial leadership and teamwork skills. She believed at the time that “Separatism was the best way to insure that women’s power was not lost!”[14]

Enrollment of women at the university increased by over 50% in the late 1950s, rising from about 1000 students to over 2000 at the end of the decade.[15] This rapid uptick in female students led to even more pressure to provide adequate housing. Dean Carmichael repeatedly lobbied for the safer and more centralized buildings to be given to the women for housing – she also requested additional locks and improved lighting to make the area safer. Her efforts were seen by some as an attempt to take over the upper quad (consisting of Ruffin, Grimes, Manly, and Mangum residence halls), and she was accused of trying to evict men to south campus. Dean Carmichael defiantly stated, “Given the choice between safer dorms for women or an integrated campus, I choose the former.”[16] The 1960s saw a rise in discontent from the students over the strict rules governing women on campus – Dean Carmichael would find herself clashing with much of the student population regarding rules such as the no apartment rule, limited visitation hours, and the requirement that women under 23 years old live in university housing.[17]

Near the end of her tenure as Dean of Women, Carmichael worked closely with the Women’s Forum (formerly the Association of Women Students, AWS) to give awards and honorary degrees to prominent women. In 1968, female varsity sports and scholarships were offered for the first time, creating a need for more space and improved training facilities for the athletes, something which Dean Carmichael advocated strongly for. One of her more important contributions during this time period was her continuous effort in collecting and distributing information to students about classes offered by the university that were about or relevant to women.[18] Through her work, it became apparent that there was a lack of women-oriented courses offered by the university – this eventually led to the proposal and creation of a Women’s Studies Program.[19]

Dean Kitty Carmichael with group of girls, 1 March 1965. [38]

Rules under Dean Carmichael

Although many of the rules were in place before Carmichael took up the position of Dean of Women, she was a main proponent in the enforcement of such rules. She firmly believed that the rules were crucial to controlling both the men and women on campus. She viewed the campus as a microcosm and the world as a macrocosm – the campus rules should reflect the rules of society.[20] Many of the regulations in place during the 1940s and 1950s were extremely strict by today’s standards: all women under the age of 24 were required to live in university residence halls on campus, slacks or shorts were not appropriate clothing choices for women, and if alcohol was present while a woman was visiting a man’s house, she was to leave immediately.

At the time, Dean Carmichael supported and enforced many of these rules, believing that it was in the best interest of the female students.[21] Most of the rules were designed to control when and where men and women met on campus; Dean Carmichael was quoted on several occasion stating that she did not want people to get the wrong idea about the university. She felt that having fewer rules would attract women that had heard of UNC’s “freedom and liberalism” and would promote so-called “loose-living.” She feared that for women, dating and dancing would become ends in themselves, preventing a proper and focused education. It is obvious that her intentions were noble and she desired to put the safety and education of the Carolina Women above all else.[22]

Many of the rules went mostly unchallenged by the student body during the 1950s, but the 1960s saw a much more open dialogue and action on behalf of the student government. The most hotly debated university rule during the 1960s was the no apartment rule. The rule stated that a woman was not to enter a man’s apartment unless there was at least another couple there. In 1963 there was a clash over the rule – a mediation board was set up to mediate the discussion between the furious student body and Dean Carmichael.[23]

Apartment Rule Coverage in the Yackety Yack Yearbook [39]

Following the no apartment rule controversy, many campus regulations governing women were scrutinized. In the late 1960s, students went even further, demanding that women be allowed to visit men in their bedrooms and vice versa. Once again afraid of the possible consequences, Dean Carmichael and the University were opposed to the rule change. However, a trial period was put in place – in 1968, the open house policy was implemented. During a visit, the students were to keep their door ajar, and several staff members remained on duty at all times during open house. The same year, the rules forbidding women under 24 from living off campus were relaxed; women over 21 could live off campus while women under 21 could live off campus if they had parental permission.

Visitation hours were also a controversial topic for the administration. Students began demanding 24/7 visitation, to which Dean Carmichael was again opposed. It was her concern that having unlimited visitation hours would distract students from studying and sleeping. The call for extending visitation hours was rejected, and visiting hours remained unchanged (lasting from noon until 1AM or 2AM, depending on academic status) for some time, although several years later the students were finally granted 24/7 visitation.[25] To oversee the ever-changing rules during this transitional period, Dean Carmichael helped form the implementation Committee to decide how to best enact and enforce new regulations. She also helped the Association of Women Students reform to become the Women’s Forum, a crucial driving force behind the advancement and celebration of women at UNC[26]

About Carmichael Residence Hall

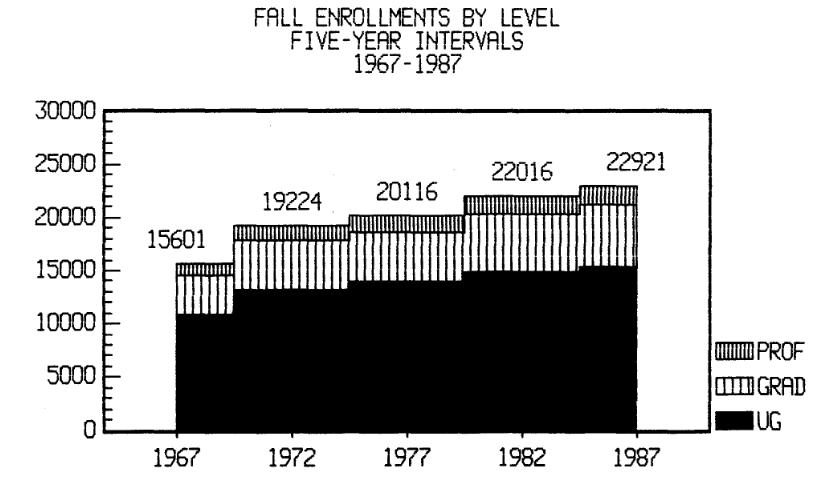

Construction of Carmichael Residence Hall, located at 101 Stadium Drive, began in early 1986 and was completed the same year.[27] The building has served as a coed dorm since it was built – the rapid construction and opening of the residence hall can be attributed to increasing enrollment trends at the University. From 1967 to 1987, total enrollment at UNC increased by about 46%, with the undergraduate population increasing by about 40% (as seen in the graph below).[28]  The building can house up to 486 students, and was originally built to be handicap-accessible and air-conditioned. [29], Carmichael Residence Hall was built with suite-style rooms, where four rooms share a bathroom. There are also several ‘singles’ on each floor (rooms for just one student instead of two), to accommodate Residential Advisors. Carmichael was built on land that was not yet allocated by the university – it was a new addition and did not replace any existing structures.

The building can house up to 486 students, and was originally built to be handicap-accessible and air-conditioned. [29], Carmichael Residence Hall was built with suite-style rooms, where four rooms share a bathroom. There are also several ‘singles’ on each floor (rooms for just one student instead of two), to accommodate Residential Advisors. Carmichael was built on land that was not yet allocated by the university – it was a new addition and did not replace any existing structures.

The residence hall was last renovated in 2008, and is currently experiencing renovations for the BlueSky Innovation Community on the ground floor, which is expected to be finished in fall, 2017. Current renovations include a “makerspace” (part of the Be A Maker program at UNC), as well as a workshop area and collaborative space for research and innovation meetings/courses.[30] Carmichael has larger and more numerous windows than the surrounding dorms, and is also structurally different. This can probably be attributed to the fact that the surrounding dorms (Teague, Parker, Avery) were all built around the same time (1958), while Carmichael residence hall was built almost 30 years later. These differences aside, Carmichael is also built from brick.

Carmichael Residence Hall is also conveniently located mid-campus, near many student facilities. Across the road from Carmichael lies Kenan Stadium, while Fetzer Field and Carmichael Arena (named after unrelated William Carmichael) are located behind the residence hall. Because of this proximity, many athletes that use Fetzer Field and the surrounding facilities elect to room in Carmichael Residence Hall. Slightly north, within easy walking distance, lie both the Frank Porter Graham Student Union and the Josephus Daniels Student Stores.

Carmichael Residence Hall, as seen from Fetzer Field. [31]

Carmichael Residence Hall. [32]

Summary of Sources and Further Reading

While it was difficult to find details about the personal life of Katherine Carmichael, the University Archives at Wilson Library on UNC’s campus has a lot of information available about Carmichael in her role as Dean of Women. There were several interviews (Margaret O’Connor and Sharon Powell), that contain of wealth of information about Dean Carmichael and the rules and rules enforced during her tenure. The book, Women on the Hill: A History of Women at the University of North Carolina, written by Pamela Dean, is both an interesting and enlightening read. It contains several funny anecdotes but also goes into great detail about how Katherine Carmichael served as the Dean of Women and the regulations she implemented during her tenure. For more information about the rules enacted by Dean Carmichael, the book An Informal History of the Women’s Rules at the University of North Carolina, written by Katherine Carmichael herself, gives a lot of insight. Information about Carmichael Residence Hall was relatively easy to find – the University housing website has a dedicated webpage with the relevant information on it.

Notes

[1] Dean, Pamela. Women on the Hill : a History of Women at the University of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Division of Student Affairs, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1987. Print. Page 16.

[2] Dean, Page 18

[3] Holbrook, H. http://carolinawomen.web.unc.edu/dean-of-women/.

[4] Alexander, Laura. Proceedings of the Katherine Kennedy Carmichael Dedication Celebrations Held at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on November 5-7, 1987 : UNC Women– Future, Present, Past. Chapel Hill, NC: The Division, 1988. Print. Page 1.

[5] “Carmichael | UNC Chapel Hill Housing and Residential Education.” Carmichael | UNC Chapel Hill Housing and Residential Education. Accessed February 25, 2017. http://housing.unc.edu/residence-halls/carmichael.

[6] Chi Omega Fraternity. Epsilon Beta Chapter (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). The North Carolina Distinguished Service Award for Women Given by Epsilon Beta of the Chi Omega Fraternity Is Presented to Katherine Kennedy Carmichael. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Epsilon Beta Chapter of the Chi Omega Fraternity, 1977. Print.

[7] Alexander, Laura. Proceedings of the Katherine Kennedy Carmichael Dedication Celebrations Held at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on November 5-7, 1987 : UNC Women– Future, Present, Past. Chapel Hill, NC: The Division, 1988. Print. Pages 3,4.

[8] “Staff | Philanthropy Central – cspcs.sanford.duke.edu.” Center for Strategic Philanthropy and Civil Society. Accessed March 27, 2017. (http://cspcs.sanford.duke.edu/about/staff).

[9] Dean, Page 18

[10] Dean Page 3,4

[11] Dean, Page 4,5

[12] Courtright, Patty. “Brief encounter triggers 100 years of women students at Carolina.” October 10, 1997. http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/oct97/100.html.

[13] Dean, Page 8

[14] Carmichael, Katherine Kennedy. An Informal History of the Women’s Rules at the University of North Carolina, 1967-1972 : with Prefatory Remarks, 1977.

[15] Courtright, Patty. “Brief encounter triggers 100 years of women students at Carolina.” October 10, 1997. http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/oct97/100.html.

[16] Dean, Page 9

[17] Powell, S. R. “Interview with Sharon Rose Powell.” Interview by P. Dean. Documenting the American South. 2004. http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/playback.html?base_file=L-0041&duration=02:11:51.

[18] O’Connor, A. M. “Interview with Margaret Anne O’Connor.” Interview by P. Dean. Documenting the American South. 2004. http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/playback.html?base_file=L-003

[19] Courtright, Patty. “Brief encounter triggers 100 years of women students at Carolina.” October 10, 1997. http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/oct97/100.html

[20] Carmichael, Katherine Kennedy. An Informal History of the Women’s Rules at the University of North Carolina, 1967-1972 : with Prefatory Remarks, 1977. Page 1

[21] Carmichael, Page 2.

[22]“Katherine Kennedy Carmichael (1912-1982) and Carmichael Residence Hall.” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed February 26, 2017. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/names/carmichael-residence-hall.

[23] Carmichael, Page 7.

[24] Dean, Page 12

[25] Carmichael, Page 8

[26] O’Connor, A. M. “Interview with Margaret Anne O’Connor.” Interview by P. Dean. Documenting the American South. 2004. http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/playback.html?base_file=L-0031.

[27] “Building Map UNC-Chapel Hill.” Building Map UNC-Chapel Hill. https://gismaps.unc.edu/buildingsearch1/.

[28] Sanford, Timothy, and Robert Cornwell. Fact Book 1987-1988. Office of Institutional Research, UNC-Chapel Hill. 1988. Page 12.

[29] “Carmichael | UNC Chapel Hill Housing and Residential Education.” Carmichael | UNC Chapel Hill Housing and Residential Education. http://housing.unc.edu/residence-halls/carmichael.

[30] BlueSky Innovation Community | UNC Chapel Hill Housing and Residential Education.” BlueSky Innovation Community | UNC Chapel Hill Housing and Residential Education. Accessed February 25, 2017. http://housing.unc.edu/residence-life/residential-learning-programs/bluesky-innovation.html.

[31] Katherine Kennedy Carmichael (1912-1982) and Carmichael Residence Hall.” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed February 26, 2017. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/names/carmichael-residence-hall.

[32] “Carmichael vs. Morrison.” The Rush Online. June 18, 2014. Accessed April 14, 2017. https://therushonline.wordpress.com/2013/06/19/carmichael-vs-morrison/.

[33] Katherine Kennedy Carmichael (1912-1982) and Carmichael Residence Hall.” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed February 26, 2017. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/names/carmichael-residence-hall.

[34] “Mary MacRae became the literary editor of the Tar Heel in 1898.” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/earlywomen/mary-macrae-became-the-literar.

[35] “Drawing of early female student from the Yackety Yack, 1907.” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed April 5, 2017. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/coeducation/drawing-of-early-female-studen.

[36] “University Women’s Club, 1907.” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed April 28, 2017. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/coeducation/university-women-s-club–1907.

[37] “Coeds in dormitory, 1948.” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed April 4, 2017. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/coeducation/item/1166.

[38] “Sheet Film 26883: Dean Kitty Carmichael with group of girls, 1 March 1965 : Scan 1.” The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/dig_nccpa/id/29056/rec/11.

[39] “Yackety Yack [1964].” DigitalNC. Accessed July 2017. http://www.digitalnc.org/.