As early as the 1950s, students were beginning to demand the building that would become the Frank Porter Graham building that now houses the Carolina Union. On February 6, 1954 Charles Kuralt , an editor of the Daily Tar Heel who went on to become a famous newsman for CBS, declared that the union at that time, Edward Kidder Graham Memorial –named for Frank Porter Graham’s uncle — was a “ragged, starving orphan” when compared to the unions at other universities. His article, along with many others that were published throughout the decade, pointed out that the small size, non-central location, tiny operating budget, and the lack of a professional director limited the utility of the union.1

, an editor of the Daily Tar Heel who went on to become a famous newsman for CBS, declared that the union at that time, Edward Kidder Graham Memorial –named for Frank Porter Graham’s uncle — was a “ragged, starving orphan” when compared to the unions at other universities. His article, along with many others that were published throughout the decade, pointed out that the small size, non-central location, tiny operating budget, and the lack of a professional director limited the utility of the union.1

Although many recognized a need for a larger physical space for the union so that it could accommodate a student population that had ballooned by nearly 300% between 1930 and 1960, funding for a new building proved difficult to procure.2 Attempts to receive state funds were denied in 1952, and again in 1960.3 Ultimately, the University borrowed $2,000,000 from the federal government to be repaid by a $9.60 increase in student fees.4

Kuralt and other students advocating for a new union constantly compared Carolina’s facility unfavorably to other unions around the country. Additionally, many universities around North Carolina were attempting to upgrade their student unions in the mid 1960s. North Carolina State University sought approval from its Board of Trustees for the construction of a new union in 1965, and in 1966 the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte also sought additions to to their unions. This wave of construction on student unions in the state reveal a push to create new spaces that could keep up with the development of North Carolina’s university system and its swelling enrollment.5

At Chapel Hill, students were at the center of the historical development of the Frank Porter Graham Student Union. The growth of the student body demanded its existence and the voice of students, through publications such as the Daily Tar Heel, advocated for its contents and central location. Student fees funded its construction and renovation and students have determined its expansion and facilities through votes. Over time, divisions in the student body have manifested themselves with the physical space of the union through conflicts over space. The story of the Student Union is the story of a changing and growing student body at UNC.

A Modern Union for a Modern University

Plans  moved forward to design and begin constructing the building once funding was approved. A model of the future building was placed in Wilson Llibrary, the main library on campus at that time, to be displayed to students.6

moved forward to design and begin constructing the building once funding was approved. A model of the future building was placed in Wilson Llibrary, the main library on campus at that time, to be displayed to students.6

The model for the new building departed greatly from the classical style of other buildings on campus. Once the model was placed in the library, students began exchanging editorials in The Daily Tar Heel over the merits of the modern architecture.

Haywood Smith, arguing for an architecturally harmonious campus contended that building in the new modern style would, in the long run, “result in a conglomeration of ‘contemporary’ (hence outmoded by contrast with subsequent construction) architecture thrown together without any apparent plan or foresight.” On the other side of the debate, Arthur Ringwalt countered that modern buildings were the most efficient means of creating spaces for modern learning. He a sked readers “isn’t having an eighteenth century campus as silly as having eighteenth century learning?”7

sked readers “isn’t having an eighteenth century campus as silly as having eighteenth century learning?”7

Whether these editorials had any real impact on the decision to move forward with the design is difficult to discern, but the continued discussion of the building throughout the building process revealed how invested students were in its creation. Few other buildings on campus received the same treatment, scrutiny, or press coverage by the student news paper as the building that students, writing in the Daily Tar Heel in 1952, hoped would become “the living room of campus.”8

The new, modern union contained many facilities that Graham Memorial did not have the space or the infrastructure for: space for Carolina Union offices, offices for student organizations, conference/seminar/meeting rooms, lounges, an information counter, a ticket sales counter, bowling facilities, room for arts and crafts, a snack bar, billiards, great hall, music rooms, dark rooms, a barber shop,” a cabaret, and a spacious office for the Daily Tar Heel.9

To maintain its functions as a modern union, the facility has been renovated since its initial construction. In 1975 the building was renovated to make sure that the facilities were handicap accessible. In 1981 the east wing was added, which included a 400 seat auditorium, dressing rooms, a ticket booth, meeting rooms, the WXYC radio station, UNC band offices, and offices for the Daily Tar Heel and, Yackety Yack yearbook. Meanwhile, the International Student Center moved into space vacated by other organizations, and an art gallery opened in the former DTH offices.10 The union was renovated again between 1999 and 2004 when the  building expanded towards south road, over a space previously occupied by a parking lot.11

building expanded towards south road, over a space previously occupied by a parking lot.11

After years of expansion, however, students voted down a 2011 plan to undertake yet another renovation. The context of a recession and the possibility of a hike of tuition from the state legislature, 54% of students who voted rejected the $16 increase in fees per semester for students over 30 years.12

The Students’ President

The new, modern union was named for progressive Frank Porter Graham, the first president of the consolidated university system. Frank Porter Graham was a controversial figure at his time, but is now most often remembered in a favorable light.

Graham graduated from UNC in 1909, and returned after completing his master’s at Columbia to become secretary of the YMCA. Graham also began to teach history at the university before being elected unanimously — and, as the story goes, unwillingly — as President of the University in 1930.13 When the University system was consolidated in 1931, Graham became President of the new UNC system and served in that role until 1949 when he was appointed as U.S. Senator.14 The consolidation process combined the management of the North Carolina College for Women (now known as the University of North Carolina at Greensboro), the North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering at Raleigh (now North Carolina State University), and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill under one office to reduce the duplication of programs and lower costs at a time when all three universities and the state government was facing a financial crisis caused by the Great Depression.15

“Open House with Frank Porter Graham, 1946.” 1946. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

As President of the UNC system, Graham was known for being focused on students. He often held open houses on sunday evenings for students to come and discuss matters with him.16 Shortly after he was appointed as a Senator, an article in the Daily Tar Heel titled “Leader of Men” praised “Dr. Frank” for always keeping at the forefront of his mind “the realization that the University is for the students, that all its activities should be in their interest.”17

Graham helped to keep the university afloat and alleviate financial pressures placed on students during the Depression when the state legislature cut funding by 25% between 1929 to 1930 and another 20% in 1931.18 Graham responded by lobbying the state legislature somewhat successfully to increase funds, and by securing federal grants from the Public Works Administration.19

Graham sparked criticism early in his presidency when he proposed the so-called “Graham plan” to reform university athletics. The 1936 proposal advocated preventing special financial aid to athletes, putting faculty in charge of athletics, limiting recruitment, ending under-the-table payment of athletes, and promoting the transparency of athletic accounts. The Graham Plan ultimately proved too controversial and failed against mass resistance.20

Conservatives such as as David Clark also critiqued Graham for his advocacy for worker’s rights. Graham published the Industrial Bill of Rights in 1930, which advocated for workers’ rights to assemble, bargain, and act democratically; proposed reduction of the sixty hour week and the elimination of night work and child labor.21 Graham also provided legal support to labor activists who were arrested when the Loray Mill Strike of 1929 ended in the violent deaths of mill worker and activist Ella Mae Wiggins, a police chief, and four others. David Clark, the voice of textile industrialists in the state, implied that Graham acted as one of “a small group of radicals who are in an insidious manner eternally fighting that which they frantically call ‘capitalism’.”22

During World War II, Graham served on the War Labor Board promoting policies which would end racial distinctions in federal labor policies.23 Graham also was involved with the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. The organization was later accused of being a communist organization. At its first meeting in Birmingham, Alabama Eleanor Roosevelt defied orders to keep the gathering segregated by sitting in the middle of the isle between the black and white sections of the audience. At that same meeting, Frank Porter Graham was elected chairman of the organization.24

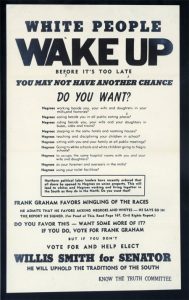

“Flyer attacking Frank Porter Graham for views on race relations, 1950.” 1950. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

By 1950, when Graham in the State Democratic Primary to become senator, Graham’s public associations with those who supported racial equality proved problematic.

Frank Porter Graham initially won a plurality of the vote in the first democratic primary election, and the runner up, Willis Smith, appeared as though he would not call for a run-off election. Around this time, two controversial Supreme Court decisions, Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, ordered small increments of racial desegregation at the university level. Given that there was an upcoming case calling for the integration of graduate programs at UNC, pro-segregationists were up in arms. In response, Jesse Helms and other Smith supporters used radio spots on WRAL radio to create a rally in favor of segregation and Willis Smith, outside of Smith’s home.25 Willis Smith, upon seeing the rally, decided to demand a runoff election.

Smith ran on a campaign of preserving segregation. Flyers were even distributed urging “White People” to “Wake up” and resist integration. Throughout the campaign, Graham was also accused of being a communist and a socialist. Through such tactics Smith and his supported managed to secure the Democratic nomination for Senator.26

Only four years later, Brown v. Board of Education legally ended practices of segregation in the public schools. And the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed a few months after Frank Porter Graham Student Union was named for the progressive president.27

When Graham learned that the new building would be named for him, he sent a letter to the Board of Trustees, to be read by President Friday, thanking them for the honor. It reads:

I wish to express to the Board of Trustees, through you, my very deep appreciation of the honor that they have done me in naming the Student Union at Chapel Hill for me. A person so honored of course is always deeply moved, not only with gratitude but also with a deep sense of humility and the wish that he be more worthy of such generous sentiments. The building will certainly meet a great need at Chapel Hill and will serve to catch up the University at Chapel Hill with the very fine student union buildings at the sister universities in Raleigh and Greensboro.

My wife, who in her quiet and devoted way was always glad to share in the life, problems and hopes of the students, joins in this expression of deep gratitude.

Sincerely and gratefully yours,

/s/ Frank Porter Graham 28

A New Heart of Campus

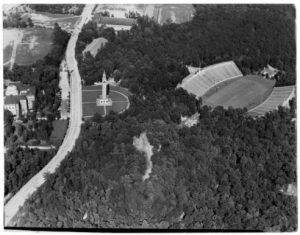

The new Union was completed in 1968 and opened to the student body in 1969.29 Around the same time and in a similar style, Josephus Daniels Student Stores and Robert B. House Undergraduate Library were completed. The new buildings were built on top of the existing Emerson Athletic Fields.30

Unlike Graham Memorial, these buildings were centrally located on the developing campus. As more student housing was placed on South Campus, the new Union was well placed in the middle of existing housing on north campus, new housing on south campus and the traditional academic quads. The construction of these three buildings created a new heart of campus on top of the old Emerson athletic field.31

Undated aerial view showing Emerson fields. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill. Click image for full information.

Aerial view showing Emerson Fields area, 1940s. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill. Click image for full information.

The three buildings, along with the older Lenoir Hall, framed a new gathering space, “the Pit,” a sunken brick-surfaced open space situated at a major crossroads between paths that lead to Polk Place (where many academic classes were located), South Campus (where new dormitories were being built), North Campus (where many other students lived), athletic facilities and dining halls. Framing this crossroads were the locations where students studied, bought their books, ate and participated in student activities.

The Pit has served many functions. It has been used as a social space where many students simply have sat and talked between classes. The Pit has also served as a space for action, activism and organization as various student organizations have either reserved or taken over pit space from the Carolina Union to use as a forum for activities, discussions, fundraisers, protests, and walk-outs.

The Pit has also served functions for the student body beyond providing a convenient space for student organizations. The Pit has also been used to hold vigils in times of tragedy, such as after the death of Eve Carson, and after the deaths of Deah Barakat, Yusor Abu-Salha, and Razan Abu-Salha in 2015.32

The Pit has served as a key gathering space for the student body and is linked spatially and organizationally to the Student Union. One of the chief ways that the the Union extends itself into the Pit, and the student body itself, is through the cubes.

A “graffiti cube” was first placed outside the union in 1971 by the Gallery Committee of the Union.33 Initially the cube was not regulated by the Union, and could be painted on a first come, first serve basis, with the unspoken rule of not painting over an event advertisement until after an event had passed. The cube was demolished and rebuilt into two conjoined cubes in 1979, and in 1980 rules were put in place requiring student groups to make reservations in order to paint the cubes.34 In 1986 the cubes collapsed and were rebuilt even bigger, with 10 panels.35The physical presence of the Carolina Union in the Pit extended the Union’s influence beyond its walls and into the new heart of campus and the student body. The cubes have served as a message board promoting the activities of student organizations.

The use of the cubes has not been without conflict. One of the more notable incidents in 1990 when when and advertisement for the Carolina Gay and Lesbian association was vandalized with hateful slurs.36 As with other union facilities, tensions have arisen and manifested, at times in vicious ways, over how the cubes are used and who gets to use them based on political and ideological tensions in the student body.

Disputed Spaces

Given that the Union serves as the central meeting space of the student body, disputes over who has access and how they use that meeting space to exert an impact on campus and campus discourse have often revealed ideological splits in UNC’s student body and the state itself.

One controversy involved the the location of the Daily Tar Heel offices in the student union. In the early 1990s, the paper published several articles, and supported various movements on campus that members of the conservative student legislature opposed. For example, the DTH called for the censorship of representative Eric Pratt after he exclaimed “You’re all a bunch of faggots” following a vote which continued funding of the Campus Gay and Lesbian Association. Pratt and others passed a bill attempting to evict the Daily Tar Heel from union offices. In response, Don Boulton, Vice Chancellor and Dean of Student Affairs, “ruled that only he and the union’s board of directors, not the student congress, had the authority to evict anyone from the premises.”37

The Daily Tar Heel also irritated conservative student legislators through its support of the effort to build an free-standing Black Cultural Center. A temporary black cultural center was placed in the union in 1986 while activists and critics fought over the existence, location and name of what would become Sonya Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History.38

When the Frank Porter Graham Student Union was built in 1968, one year after the formation of the Black Student Movement, the university was still in the beginning stages of effective integration and race was a key and contentious issue on campus and in the surrounding community.39

In 1970, James Cates, a black man who worked on campus, was stabbed in the Pit by members of the Storm Troopers, a white motorcycle gang. In an interview with the Southern Oral History Program, his cousin, Nate Davis who was working at the Union at that time, recalled leaving the scene to tell James’ mother and returning to find James still lying on the ground, having not been attended to by medics or taken to the nearby hospital. Eventually a police officer took James to the hospital, but in the interview Nate expressed feeling as though police were more concerned with getting the white gang members out of the area than they were with saving James’ life. All of the men involved were found not guilty, and demonstrations and fire bombings occurred in Chapel Hill after the trial.40

Forty-four years later, a protest was held in the Pit following the decision of a jury to not indict Police Officer Darren Wilson, after he shot Michael Brown, a black teenager, in Ferguson, Missouri. Students walked out of class, held a die-in, and carried signs stating “Black Lives Matter.”41 Race, racial inequity, and racial discrimination have historically been and remain key areas of contention on campus. The Union has served as a space created for and occupied by students and is one in which racial, political and cultural divisions among the student body have become evident.

The Students’ Union

The Frank Porter Graham Student Union was created by, for and with students. It was named for a President who was beloved by many of his students, and now borders upon and interacts with the heart of student life on campus. It serves as a key backdrop for major events within students life as well as the day to day happenings of student life at Carolina. Shaped for, by and with an ever-evolving student body, an examination of Union history can serve as a gateway to understanding major changes within and divisions among the student body.

To learn more about Frank Porter Graham, check out these resources:

Dr. Frank: The Life and Times (a documentary on Frank Porter Graham)

The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of History exhibit on Frank Porter Graham

- Charles Kuralt. “Our Student Union: A Ragged, Starved Orphan.” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Feb. 6, 1954. (pictured)

- Richard Watt. “A Condensed History of the Carolina Union” (Presentation, Carolina Union Board of Directors, 2014), 4.

- Charles Kuralt, “Our Student Union.”; BOT Minutes. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

- Sub group 1: Minutes. Volume 9. Jun 1964- Feb 1966, 278. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill. ; Ernie McCrary.“Fee Hike Planned for Fall.” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), Feb. 2 1965.

- Sub group 1: Minutes. Volume 9. Jun 1964- Feb 1966, 420,427. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

- Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), Sept. 17 1964. (pictured)

- “Student Union Plans Raise Roof.” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), Nov. 14 1964. (pictured)

- “The Case for a Student Union.” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), May 13 1952.

- Buildings Notes, compiled by Rachael Long (Chapel Hill: Facilities Planning Office), December 14th 1984, 146.; Richard Watt. “A Condensed History of the Carolina Union” (Presentation, Carolina Union Board of Directors, 2014), 4-5.

- Buildings Notes, compiled by Rachael Long (facilities planning office), December 14th 1984, 147.

- Richard Watt. “A Condensed History of the Carolina Union” (Presentation, Carolina Union Board of Directors, 2014), 1.

- Katia Martinez. “Union Renovation Doesn’t Pass” Daily Tar Heel, Feb. 20, 2011.; Melissa Abbey. “Students voice opposition to fees for Union renovation,” Daily Tar Heel, Jan. 1, 2011. (pictured)

- William D. Snider. Light on the Hill. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992) 203-207.

- William D. Snider. Light on the Hill. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992) 212.

- William D. Snider. Light on the Hill. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992) 212.

- http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/graham/open-house-with-the-president-1946/

- “Leader of Men.” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), Mar. 24 1949.

- William D. Snider. Light on the Hill. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992) 208-209.

- William D. Snider. Light on the Hill. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992) 226-277.

- Kenneth Zogry. Print News and Raise Hell: The Daily Tar Heel and the Evolution of a Modern University, Chapter 2, 23.

- Albert Coates. Edward Kidder Graham, Harry Woodburn Chase, Frank Porter Graham: three men in the Transition of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from a Small College to a Great University. (1988) 55-57.

- Snider, William D., Light on the Hill. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992) 205-206.

- Snider, William D., Light on the Hill. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992) 236.

- Kenneth Zogry. Print News and Raise Hell: The Daily Tar Heel and the Evolution of a Modern University, Chapter 2, 31.

- Julian M. Pleasants. Frank Porter Graham and the 1950 Senate Race in North Carolina. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1990) 195-199.

- Snider, William D., Light on the Hill. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992. 236

- Sub group 1: Minutes. Volume 9. Jun 1964- Feb 1966, 421-422. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

- Sub group 1: Minutes. Volume 8. sep 1962- May 1964, 507. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

- Richard Watt. “A Condensed History of the Carolina Union” (Presentation, Carolina Union Board of Directors, 2014), 1.

- “Aerial View.” Undated. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill

- Kenneth Zogry. Print News and Raise Hell: The Daily Tar Heel and the Evolution of a Modern University, Chapter 5, 38.

- Vigils for Slain UNC Student Body President Draw Thousands” WRAL, Mar. 06 2008. Retrieved from: http://www.wral.com/news/local/story/2534527/ ;Travis Long. Thousands gather at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Pit to mourn. February 11th 2015. http://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/counties/orange-county/article10859798.html

- Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), Mar. 25 1971.

- Karen Barber. “Union Landmark Dies, Has Twins,” Daily Tar Heel, Aug. 28, 1979; Bill Ragland. “Union Clarifies Guidelines for Cube Use,” Daily Tar Heel, Nov. 17, 1980

- Tom Camp. “Pit to get bigger cube to cover old paint spot,” Daily Tar Heel, Aug. 27, 1986

- Thomas Healy. “Vandalism of Cube shows hatred of CGLA members” Daily Tar Heel, Oct. 15, 1990.

- Kenneth Zogry. Print News and Raise Hell: The Daily Tar Heel and the Evolution of a Modern University, Chapter 5, 50-51.

- Kenneth Zogry. Print News and Raise Hell: The Daily Tar Heel and the Evolution of a Modern University, Chapter 5, 50.

- “The Black Student Movement at Carolina,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Retrieved from: http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/black_student_movement/founding_1967/

- Oral History Interview with Nate Davis, February 6, 2001. Interview K-0538. Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) in the Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Jenny Surrane, “Hundreds of students stand in solidarity with Ferguson protests,” Daily Tar Heel, Nov. 25, 2014.

![FPG.StudentUnion_c.1969[1]](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2015/12/FPG.StudentUnion_c.19691-300x225.jpg)

![FPG.PIT_and_CUBE_c.1970[1]](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2015/12/FPG.PIT_and_CUBE_c.19701-300x225.jpg)