By Chris LaMack

Bryan Grimes – a man known to all as “the Colonel” – never served in the military.

He was a colonel, though not in the typical capacity; he was appointed one by North Carolina governor Elias Carr in 1893, as a member of the governor’s staff – an aide-de-camp.[1] The NC native was a man of so many titles in so many organizations that his style may just as well have been “Joiner Grimes” as “Colonel Grimes”: he was a farmer, an executive, a president, a civil servant, a historian.

Yet he was known for much of his lifetime, just as he is remembered today, as Colonel. As to why this particular epithet was and is so resilient, we can only speculate. Perhaps ‘colonel’ was Grimes’ proudest rank; perhaps it pleased a man lauded by his contemporaries as a hard and dedicated worker to be known as a leader of middling status, close to both his people and his state. Perhaps it marked him as a member of an old military lineage, a heredity supplied by his imposing family name: Grimes, one of North Carolina’s respected “Southern aristocracies.” As both a statesman and an historian, he might have valued the link to his predecessors. Possibly, “Colonel Grimes” served to differentiate him from his father and namesake, General Bryan Grimes, who spent the bitter years of the American Civil War commanding North Carolina troops in the Army of Northern Virginia. Maybe the Colonel aspired to live up to his father’s reputation; maybe he tried desperately to escape the General’s long shadow.

Whatever the case, the appellation and the man were inextricable even in death. By the time professor M. C. S. Noble penned Grimes’ obituary in February of 1923 for UNC’s Alumni Review, his subject had been North Carolina’s Secretary of State for over two consecutive decades. Despite even this, Noble’s headline offered readers of the Review the sober news that “Colonel J. Bryan Grimes” had passed away.[2]

The cornerstone of Grimes Dormitory (now Grimes Residence Hall) today. Photographed by the author. Click to enlarge.

Grimes Residence Hall (101 Emerson Drive, Chapel Hill, NC) is – as it has been since its completion in 1922 – a dormitory on what today is commonly referred to as Carolina’s ‘Mid-Campus’. Officially, it comprises the northwestern corner of the Upper Quad, adjacent to the northeast to Manly Residence Hall, to the southeast to Ruffin Residence Hall, and bounded to the north and west by Cameron Avenue and Emerson Drive, respectively. Grimes (along with Mangum, Manly, Ruffin, Old East, and Old West) is part of the Olde Campus Upper Quad, a community of upperclassmen and sophomores. The district is often touted as the heart of ‘old’ campus, and is noted for its proximity to the greater part of non-medical class buildings, the gyms, athletic facilities, and Kenan Stadium, and to the attractions of Franklin and Rosemary Streets.[3] The four corners of the quad itself – Mangum, Manly, Ruffin, and Grimes – are most noteworthy for their similarity to each other, and, frankly, for little else, excepting their worth as well-kept examples of the Colonial Revival style. They are not large buildings, but they do possess a quiet air of stately dignity. There is no question in the mind of the observer that they belong on a university campus.

In one of a number of intentional parallels to Old East, the first university building to be built on Carolina’s campus, Grimes’ cornerstone laying was Masonic, and the block is inscribed with the name of J. Bailey Owen, the Grand Master who conducted the ceremony. Photographed by the author. Click to enlarge.

Unlike Old East and Old West, the four buildings of the quad proper are less than a century old: construction on Grimes, the first to be raised, was begun in 1921 and swiftly concluded the following year. Built with public money, the 21,752 square foot dormitory originally contained bedrooms for 103 occupants.[4] (The current population is listed as 88.)[5] Grimes has been subject to a few modernizations over the years, none of which have altered the character of the quaint residence. The dormitory is named for J. Bryan Grimes, whose name (in one of those turns of historical fact that wouldn’t seem out of place in a UNC trivia match) also appears on the building’s cornerstone, where he is listed as the chairman of the building committee.

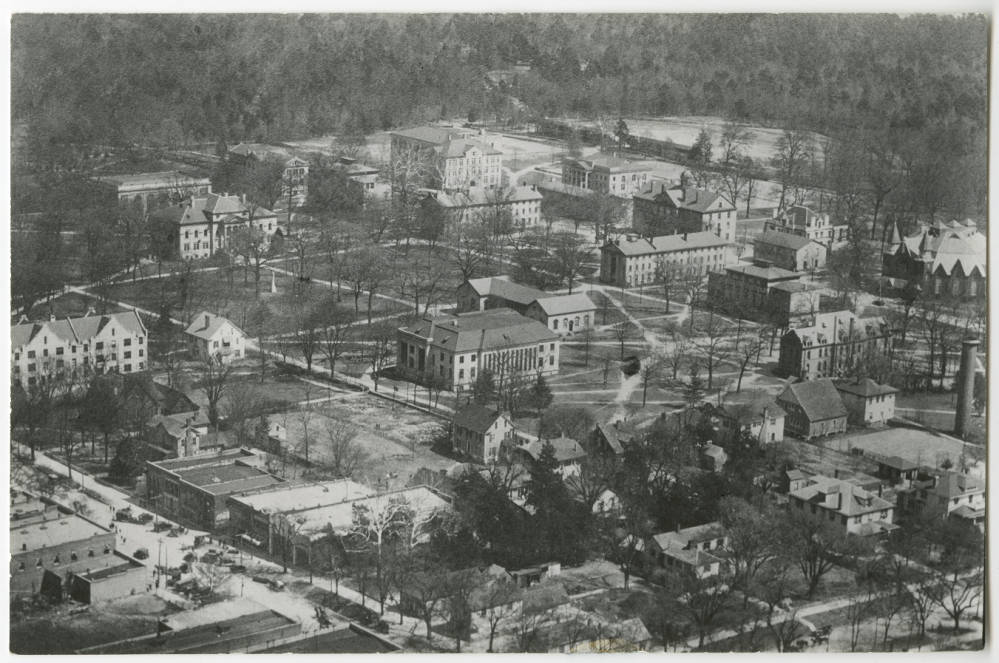

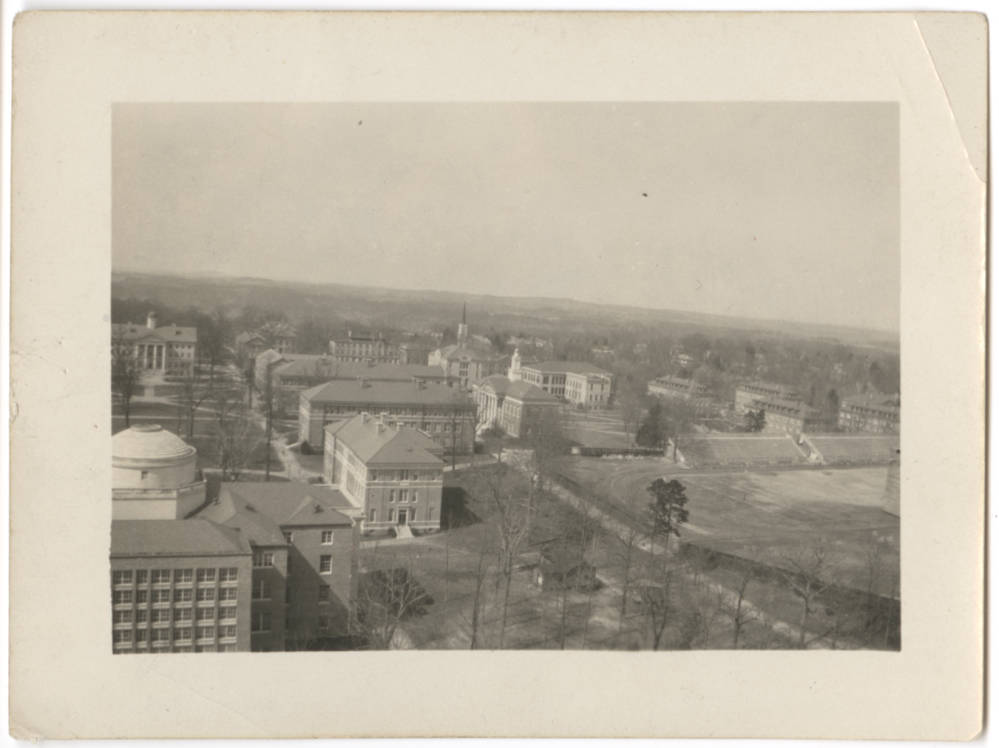

An aerial view of Carolina’s campus as it looked from the west in 1919, on the eve of the monumental development project of the 1920s. From a copy in the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

Carolina’s campus as seen from the air in 1931, after the construction boom of the 1920s. From a copy in the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

It is difficult to imagine how a fairly unassuming dormitory and its imposing but strangely remembered namesake civil servant could be implicated in a genuinely unparalleled shift in the direction and purpose of the United States’ first state university. Yet both were instrumental in the re-creation of the University of North Carolina as a bona fide research institution and a truly modern university – inaugurated in 1921 with a breathtaking expansion program under president H. W. Chase. This growth is intimately tied to the conception of Carolina as a “Southern” institution, and throughout the development scheme there was a concerted effort to construct such an identity for the university. This is one story through which we might make sense of each of these four elements – J. Bryan Grimes, Grimes Dormitory, the expansion of UNC in the 1920s, and this multiangular Southern self-conception for the institution – in the context of each other.

“An Extraordinary Development”

At the close of the First World War, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had been in the business of enrolling students for nearly a century and a quarter. It had weathered a civil war, even managing to open its doors again in 1875 after a five year hiatus while student numbers recovered from the decimating conflict. Nothing, however, could have prepared the institution for 1920.

In the autumn of that year, high school enrollment in North Carolina’s public schools swelled to 26,000 – with more drastic increases expected. Archibald Henderson notes that, “largely in consequence of the first World War…a greatly increased enrollment in the high schools was rapidly shifting the burden of accommodation to the colleges and the State University”.[6] For the 1920-21 academic year, the university expanded to incorporate an unprecedented 1,547 students, “overwhelming dormitories, boarding houses, classrooms, and laboratories.” Even so, Carolina was forced to turn away 2,308 additional applicants.[7] Henderson records that “dormitories built to house 469 were housing 738, under highly uncomfortable and unsanitary conditions, with four students in rooms designed for two. Dining halls designed for 450 were actually feeding 725. Excepting lecture space in scientific and professional buildings, there were only 19 classrooms on the entire Campus available for general teaching”.[8] N. W. Walker, the Director of the Summer School in 1920, summarized the scope of the problem in his report to the president for that term, under the understated subheading “Lack of Adequate Accommodations”:

“While the Summer School was in session the accommodations of the campus and the town were taxed to their limit of comfort – if not beyond that point. Before the school opened over 400 applications for admission had to be declined because we were unable to find rooms enough to take care of them. Had our accommodations been adequate, the attendance upon the 1920 session would have reached 1800 or 2000. But here I am pointing out a problem that is just as acute in the regular session, and I need not dwell further upon it.”[9]

This surge in demand for university enrollment in North Carolina represented no less than “an extraordinary development, amounting to a crisis in the history of the evolution of higher education in North Carolina”.[10]

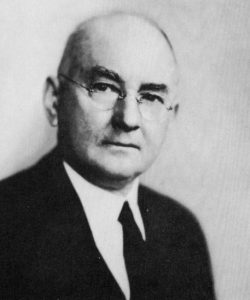

Louis R. Wilson, who argued that significant expansion would be necessary for the university. In Powell, Lewis. The First State University. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979. Click to enlarge.

During the war, an ambitious campus development program was proposed under president Edward Kidder Graham. By the time the president had tragically succumbed to the infamous 1918 Spanish Influenza epidemic, however, only a few preliminary steps had been taken. The plan was effectively shelved while the university reeled from the epidemic. In 1919, Louis Round Wilson addressed a memo to UNC’s new president pleading for expansion; Wilson suggested a “fund-raising campaign to secure $5 million from private sources and a public appeal to the people and the General Assembly for more state support for the multitudes of students seeking college education.”[11]

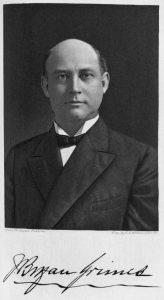

Harry W. Chase, President of the University of North Carolina from 1919 to 1930. In Powell, Lewis. The First State University. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979. Click to enlarge.

Harry Woodburn Chase was an unlikely candidate for president of the University of North Carolina; Chase himself was bewildered by his appointment, describing his victory “as having been ‘rather wished on me because I happened to be on the spot, rather than through any particular deserts of my own.’”[12] A New England Native, the new president struck one skeptical North Carolina journalist as “‘a damnyankee, a genuine, blown-in-the-bottle Massachusetts bluebelly’”; he was only the third non-North Carolina native ever to head the university.[13] The softspoken, prematurely silvered Chase nonetheless would prove himself a man of firm conviction, devoted to his ideal of “‘responsible freedom’” as the ‘common business of education and the democratic state’”.[14]

Not to be bowed by the impressive challenge he inherited, Chase quickly moved to free the stuttering development program. In his first report to the university Board of Trustees in 1919 – entitled “The University and the South” – the president “summarized the material advance of the region and prophetically declared, ‘My own conviction constantly deepens that the next great creative chapter in the history of the nation is to be written here in the South…Somewhere in the South there must inevitably grow up an institution…which typifies and serves and guides this new civilization…My dream for the University of North Carolina is that she be nothing less than this.’”[15] The former philosophy professor had clearly and cleverly crafted his stance for the maximum effect on his audience. His appeal to the emerging self-identification of “the South” by reform-minded Democrats as a new bastion of progress (in spite of the alleged “victimization” of the region under Reconstruction-era Republican rule, according to this “redemption” narrative), as well as the Presbyterian (“Southern”) value of self-improvement through hard work, challenged the trustees – and later the North Carolina Legislature and the governor – to see development as a patriotic duty, and called into question the “Southern” identity of any who voiced their unease at the staggering costs of the expansion.

On University Day (October 12), 1920, Chase used his address to confront the challenges facing Carolina. The day’s ceremony culminated in the official presentation of a famous portrait of William Richardson Davie to the university on behalf of a group of Davie’s descendants; the president used the opportunity to compare the struggles of his era to those that faced the university father at Carolina’s inception.[16] The message was clear – a failure to adapt the university to the changing times was a betrayal of Davie’s legacy and patrimony, and an all-or-nothing refutation of the foundational ideals of the University of North Carolina.

Harry Chase’s grand vision was enthusiastically shared by an influential trustee, a one-time graduate of the university, who would prove just as ambitions as the president. His name was Grimes.

“No More Obliging Officer”

John Bryan Grimes was born on the 3rd of June, 1868, to a well-known North Carolina family. His mother, Charlotte Emily Bryan Grimes, was the daughter of John Heritage Bryan, famous lawyer and congressman. His father was Bryan Grimes – “General Grimes” to most. Upon the elder Grimes’ graduation from UNC in 1848, his father gave him Grimesland, the family plantation in Pitt County, North Carolina, through which he came into possession of around one hundred enslaved Africans. (A short video about the preservation of the home appears on the Town of Grimesland’s website and can be viewed here.) At the North Carolina State Convention in May of 1861, he was among the most outspoken secessionists. (He would keep for the rest of his life as a personal treasure the pen he used to sign the Ordinance of Secession.) He resigned his seat immediately after the convention to accept a commission as a major in the Confederate army; he received a number of promotions, eventually surrendering the Fourth North Carolina Regiment with a major general’s rank. He maintained a successful agricultural operation after the war until his assassination in 1880.[17]

J. Bryan Grimes. In Haywood, Marshall DeLancey. “J. Bryan Grimes.” Biographical History of North Carolina, Vol. VI. Ed. by Samuel A. Ashe. Greensboro: Charles L. Van Noppen, 1907. Click to enlarge.

John Bryan – who went by his father’s name and generally appears as “J. Bryan,” was raised on the family plantation, attended by private tutors prior to a stint in a number of renowned academies beginning at age 12. He enrolled in the University of North Carolina in 1882, and graduated with the class of 1884. “After leaving the University,” records contemporary biographer Marshall Haywood, “he perfected himself in business methods by a course in the Bryant and Stratton Business College, of Baltimore,” where he worked on learning how to manage Grimesland and the family’s extensive land holdings left in disarray by the General’s death.[18] His penchant for meticulous organizational work would come to serve him well not only as a planter, but later in his career.

Though he moved in political circles – resulting in his appointment as aide-de-camp to Governor Carr – his election to Secretary of State on the Democratic ticket in 1900 was Grimes’ first elected office. The Colonel’s proponents emphasized his agrarian character and touted his loyalty to North Carolina farmers; Haywood speaks of a “devoted agriculturalist” who “sought to advance the true mission of that great body of farmers [the Farmers’ Alliance of North Carolina, which Grimes became a member of in 1899]” and who, “though a devoted Democrat, did not seek to advance the interests even of his own party through the instrumentality of that society”.[19] Indeed, Grimes served in a number of agrarian capacities during his tenure, both officially and unofficially: the North Carolina Agricultural Society (Executive Committee), the State Board of Agriculture (“where his knowledge of the interests of the agricultural classes made him a most valuable worker and committeeman”)[20], the Tobacco Growers’ Association (President), and the Farmers’ Educational and Cooperative Union and the State Grange (member).[21] Haywood presents a flattering synopsis of Grimes as a competent, energetic, and devoted civil servant:

“As a public speaker Colonel Grimes has few equals in North Carolina. He is master of vigorous English, seldom finding occasion for the use of notes, and as a debater on political matters is bold and aggressive. He is a true lover of his State and its people; and, together with his brothers, has liberally contributed both time and money to the cause of religion, education, and industrial development…[T]here is little doubt that greater honors will attend his future career, for no more obliging officer has ever served the State, and the people are not slow to recognize the merits of men efficient in public work, clean in private life, courteous in manner, and faithful to every trust.”[22]

Grimes also had a passion for history – particularly North Carolinian history. He was active in the American Historical Association and the North Carolina Historical Commission (which he chaired for a number of years), an Executive Committeeman of the State Literary and Historical Association, and a Manager of the North Carolina Society of the Sons of the Revolution; he was instrumental in the development of the North Carolina Hall of History.[23] As Secretary of State, Grimes collected and organized thousands of official documents that had collected over decades in the office and made them available to the public. “In instances where old wills and other documents are becoming illegible on account of age, and in danger of falling to pieces,” lauds Haywood, “he has had copies carefully made for preservation”.[24] He was the author of a number of works dealing with North Carolina history and culture.[25]

Grimes had a particular passion for the history of Civil War – the conflict that Grimes’ own father had played such a dynamic role in shaping, and in the early twentieth century still so recent that living veterans were a fixture of life: “In matters relating to Confederate history and the welfare of surviving veterans he is an enthusiast.”[26] As Secretary of State and a respected orator, Grimes delivered addresses at the unveiling ceremonies of a number of monuments, including several Confederate memorials. Haywood hails the Colonel’s 1905 speech at the erection of the Virginia-Carolina Monument and Wyatt Memorial in Bethel, Virginia as “a splendid contribution to the literature relating to North Carolina’s war record.”[27] That sermon, addressed primarily to “Your Excellency, Veterans of Virginia and North Carolina,” opens with a long and flowery treatise on the entwined histories of the two states from the beginning of the Colonial Period, with particular service to the role of Sir Walter Raleigh (“the knightliest figure of that heroic age”) and North Carolina’s role in “driving the foe and the red man from your borders”.[28] Having come around to the Civil War, it continues:

“Forty-four years ago to-day was fought the first battle of the great war which was to drench our land in blood, slay the flower of our manhood, desolate our homes, widow our women, starve our children and destroy the mighty fabric of State Sovereignty.

“When the wires flashed the shock of battle to the world half a million Southrons sprang to arms. The mansions on the great plantations gave up their petted cavaliers, scions of a knightly race who knew no fear; the farmer and the laborer gave their only sons…In the rain of battle they knew no class distinction – valor was their code and the bravest were the greatest – Patriotism was their religion, and it seemed they believed with Eastern fanaticism that falling face to the foe meant translation to the Elysian shore. In the march of death they went forth as schoolboys to a May festival. No burnished helmets encircled their brows; no gilded trappings adorned their breasts. They were not arrayed in all the rich panoply of war – but on their cheeks there shone jewels richer than the Kohinoor’s ray – ‘twas the Carolina woman’s tear, and for her and their native land they went forth to battle and to die…

“We came to Bethel 800 strong – the flower of Carolina’s chivalry. Eager for battle and hungry for glory were the heroes we sent you. Heroes bearing illustrious names in their native land – names to which added honors came…”[29]

A pamphlet containing Grimes’ Bethel speech. In the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

The address is, of course, immediately striking for its painfully obvious racial overtones – established by the crude amalgamation of the rich cultural milieu of indigenous Southeasterners and their vilification as “the red man” and the orientalist tropes embodied by Grimes’ references to “Eastern fanaticism” and the “Kohinoor’s ray.” But it also reveals an important facet of Grimes’ conception of American (and specifically North Carolinian) history: the Colonel was apparently very deeply committed to the “Lost Cause” narrative, the historiographical convention that portrayed the Confederacy as a tragic champion of states’ rights and individual liberty, and that viewed the victory of the Federal Government through attrition and the subsequent period of Reconstruction (which saw the widespread elections of Republicans and particularly African-Americans in districts with newly enfranchised former slaves) as the oppressive actions of a harsh, undemocratic military regime.

The language of the Virginia-Carolina address (the full text of which can be read here) practically drips with sentimentality for the Confederate cause; Grimes unsubtly celebrates Confederate soldiers as “scions of a knightly race” and patriots – a charged word clearly intended to draw a parallel between Southern secessionists and American revolutionaries (which feature prominently in the lecture’s prologue), and to insinuate that the rebels of 1861-65 continued the tradition of those of 1775-83. The Colonel pointedly laments the vicious nature of the war while ascribing no responsibility for it to the Confederacy; his contrasting depictions of valorous Southern heroes all but lay the blame for wanton devastation squarely on the US government. Conspicuously, the ten page treatise on the “War Between the States” makes no reference whatsoever to slavery.

Bryan Grimes, true to his image as an active and involved statesman, also served for a number of years as an Executive Member of the University of North Carolina Board of Trustees. In this capacity, the Colonel was tasked in 1919 by President Chase to “investigate the feasibility of developing the grove in the south campus for building purposes.”[30] Archibald Henderson writes:

“[Grimes] brought prominently into the foreground a plan he had long advocated for developing the 550 acres of woodland adjoining the 48-acre Campus. After studying plans of the leading American Universities, he sent out a letter embodying his ideas to the Trustees and many of the alumni. Among other things, he said: ‘Instead of pressing and crowding towards the village street, [the University] should handsomely expand towards the south, as the original plans contemplated…A competent, broad-minded and sympathetic landscape architect could lay off college and park grounds unequalled anywhere in the country. The avenues, parks, squares, circles, and vistas would bear names of men associated with University life and history…With the new era that has dawned for the University, now is the time for this development.’”[31]

Thus, Grimes laid the groundwork for the sweeping construction program that would see the hundred and twenty-five-year old university practically double in size in just a decade. South Campus (now called “Mid-Campus”) would be the site of the new University of North Carolina. And it would start with Grimes Dormitory.

“The Greater University”

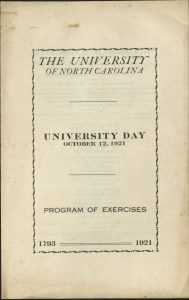

An original program for the 1921 University Day festivities. In the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill. Click to enlarge.

Exactly one year after drawing a parallel between the university’s most pressing issue of the early twentieth century and the trials of UNC’s founder, William Davie, Harry Chase inaugurated the new era of expansion in the same way that Davie had inaugurated the university itself: with a cornerstone laying ceremony. Amidst great fanfare, the president promised that “The greater University that shall rise will shelter men in numbers that they of the past scarce dreamed of, will number her buildings by scores.”[32] One hundred and twenty-eight years – to the day – before, William Davie had dedicated Old East. Now, in 1921, Chase was dedicating the first building of the new university.

The University Day program schedule. Note the reference to the cornerstone laying ceremony at the “New Dormitory Quadrangle”, which took place at Grimes Dormitory. In the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill. Click to enlarge.

This first edifice was Grimes Dormitory, which, along with Mangum, Manly, and Ruffin – the four corners of the upper quad – was planned and constructed to fill the university’s desperate need for additional living space. Technically, Steele Dormitory preceded Grimes on South Campus, but the current location of Academic Advising services was a single project – unlike Grimes, the first of a slew of building projects that would come to dominate the area around what is today Polk Place.

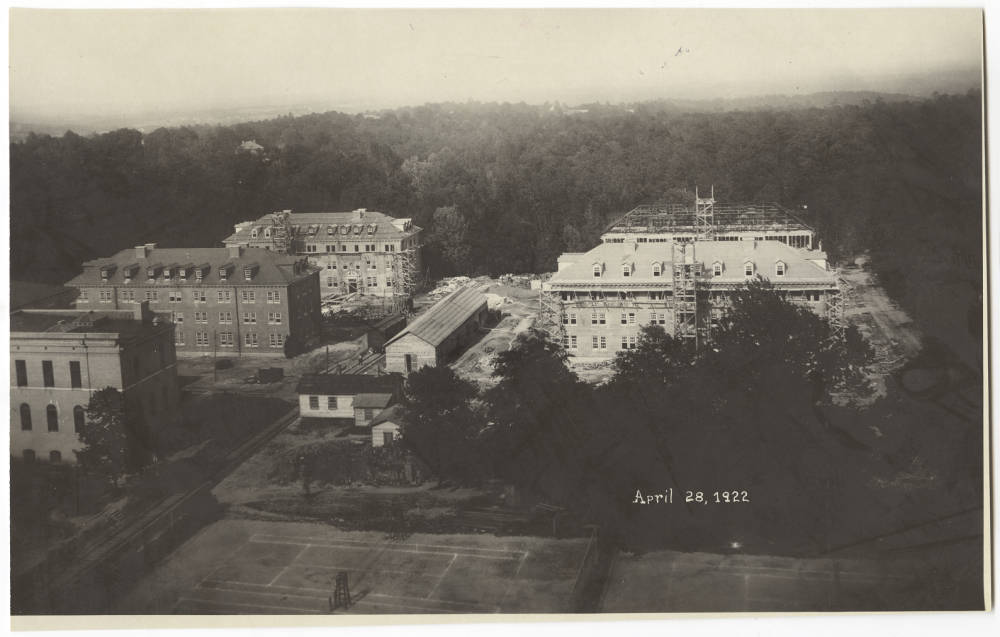

The Upper Quad dormitories under construction, April 28, 1922, showing the nearly completed Grimes (partially obscured by Caldwell Hall) at center left. The railroad spur used to transport building materials to the site can be seen running diagonally from the lower left corner. From a copy in the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

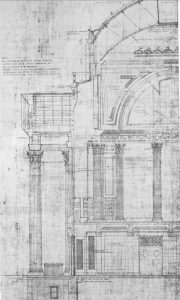

The new dormitory was designed by H. P. Allen Montgomery of the North Carolina based architectural firm of Atwood and Nash, and the man who would go on to design Manning and Murphey Halls as well as the former Saunders Hall (currently called Carolina Hall). The New York based McKim, Mead and White consulted on Grimes, as they did on the entirety of the campus development project in the 1920s. The designers, best known as proponents of the late Romantic classical school of architecture, nonetheless attracted the attention of President Chase partly through the work of partner Charles Follen McKim, who, “at the beginning of his career in the 1870s, was an important initiator of the Colonial Revival.”[33]

The eastern arm of Polk Place, showing Manning, Murphey, Saunders (Carolina), and Bingham Halls, the heart of the Colonial Revival movement on Carolina’s campus, in the 1930s. Wilson Library, completed in 1929, is partially visible from the rear at bottom left, as is the then-new portico of South Building, at center left. Grimes, Mangum, Manly, and Ruffin dormitories can be seen at center right. From a copy in the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, Chapel Hill.

Insert of Arthur Nash’s sketch for the front of Wilson Library, the Neoclassical capstone to the Colonial Revival heart of South Campus. In Alcott, John V. The Campus at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill Historical Society, 1986. Click to Enlarge.

The Colonial Revival style was appealing for a number of reasons. First, it was felt that a Colonial face on the project of expansion would tie the new to the old artistically; it felt natural on such an historic campus, in the words of John Alcott, to “apply Colonial details to the surface of a building, thereby conferring instant tradition, making the structure as American as apple pie.” The rise of the convention as the quintessential American architecture predated UNC’s expansion by nearly a half century, when examples were displayed at the Centennial Exposition in 1876. In 1897, a Westover doorway – a feature of Colonial Revival architecture, a decorative door frame in plaster relief – was installed on South Building. The body of design not only recalled the time of the Revolution, it was itself considered revolutionary: it was a revolt against the dominant European model of Romanticism, and it rose to prominence at a time when American arts began to celebrate their uniquely American roots. The university expansion itself “was launched in 1921, during jubilation after World War I, a good time for the expression of Americanism.”[34]

The portico installed on the southern face of South Building – also designed by Nash – circa the 1920s. In Alcott, John V. The Campus at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill Historical Society, 1986. Click to Enlarge.

But “Americanism” was not the only identity constructed by the choice of Colonial Revival for the project. “More to the point in Chapel Hill,” continues Alcott, “according to experts advising the University, the revival would be of Southern Colonial: ‘Old architecture of the South is distinguished by great dignity and picturesque charm lacking in northern Colonial types. There is an opportunity for a renaissance of Southern Colonial at Chapel Hill.’”[35] Thus, the style was carefully crafted to accentuate Carolina’s “Southern” roots. The substance of those roots, however, is less clear.

Saunders (Carolina), Manning, and Murphey Halls in the mid- to late-1920s. The Upper Quad residential community is visible to the left of Manning. In Powell, Lewis. The First State University. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979. Click to enlarge.

To J. Bryan Grimes, the new face of the University of North Carolina would have embodied what he perceived as the dignity and nobility of the Antebellum South, which, ravaged by warfare and occupation, was in the midst of its rebirth. Chase, quite likely, left his ideas as to the effect of the new campus intentionally ambivalent. That the creation and solidification of a Southern identity for the university was so emphatically encouraged by a New Englander certainly suggests a more complex notion of what the designation implies than might be imagined – though the inclusivity certainly had its limits.

Grimes lived to see the completion of his building, and his influence on the new campus landscape continued until his death in 1923. He remained an active Executive of the Board of Trustees, and was on the board that confirmed the names of the rest of the dormitories in the Upper Quad, as well as the first three academic buildings of the expansion, on Polk Place’s eastern arm – including Saunders Hall, named for another “Lost Cause” subscriber, William Saunders. Harry Chase’s dream of expanding the university was realized: In 1920, Carolina was full to bursting with 1,547 students. By the end of the 1920s, the university housed over three thousand.[36]

Grimes Residence Hall stands today where it has stood from the beginning; its cornerstone is the same cornerstone laid by President Chase in October of 1921, the cornerstone which set the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on the path to its reinvention as a fully modern research university – and which catalyzed the maturation of its Southern identity, the legacy of which remains the subject of much healthy campus debate. The building itself has undergone only slight changes through the decades: the installation of telephones in 1969; the accessibility renovations of 1975; the enclosure of the stairwells in 1979 (which surely represents a potential source of amusing anecdotes for the curious researcher). As a dormitory for naval cadets during the Second World War (refitted for the purpose in 1942), Grimes is tied to the experiences of servicemen and servicewomen on Carolina’s campus, which could very well be examined – a worthy project that is well beyond the scope of the research presented here.

The North Carolina Collection housed at Wilson Library (fittingly, a building tied inextricably to the campus expansion of the 1920s and the flowering of Carolina as a fully-fledged research university) houses a wonderful collection of documents and publications covering a broad spectrum of university functions, as well as a number of valuable works on campus and state history. Noteworthy among these latter resources are William Snider’s Light on the Hill, Archibald Henderson’s Campus of the First State University, and Louis Round Wilson’s University of North Carolina: 1900-1930. John Alcott’s Campus at Chapel Hill contains a useful – and readable – examination of campus architecture and architectural design, and William Powell’s First State University brings together a fascinating photographic and ephemeral record for UNC and for North Carolina. A great many campus artifacts and material remains are curated by the UNC Research Laboratories of Archaeology, and these are well worth investigation by any university history researcher or even the simply curious. Special thanks to North Carolina Research and Instruction Librarian Sarah Carrier for her invaluable support on this project, and for sharing my enthusiasm for campus history.

[1] Noble, M.C.S. “Colonel J. Bryan Grimes Dies,” Alumni Review. February, 1923. http://www.carolinaalumnireview.com/carolinaalumnireview/192302?search_term=J.%20Bryan%20Grimes&doc_id=-1&search_term=J.%20Bryan%20Grimes&pg=14#pg14 Accessed 2/26/17.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Olde Campus Upper Quad,” Housing and Residential Education, accessed 2/23/17, https://housing.empire.ovcsa.unc.edu/residence-halls/community/olde-campus-upper-quad

[4] Long, Racheal, “Grimes Dormitory. Building Notes. Chapel Hill: Facilities Planning and Design, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1993. 151.

[5] “Olde Campus Upper Quad”

[6] Henderson, Archibald. The Campus of the First State University. Richmond: The William Byrd Press, 1949. 238.

[7] Snider, William D. Light on the Hill. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992. 173.

[8] Henderson, 238

[9] “The University of North Carolina Record, December 1920, Number 172” University of North Carolina Report of the President, 1919-1924 in the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill. Call No. C378 UC. 81.

[10] Henderson, 238.

[11] Snider, 173.

[12] Ibid., 169.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 172.

[15] Ibid., 177-8.

[16] Ibid., 174.

[17] Daniels, James D. “Grimes, Bryan.” Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Vol. 2 (D-G). Ed. by William S. Powell. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

[18] Haywood, Marshall DeLancey. “J. Bryan Grimes.” Biographical History of North Carolina, Vol. VI. Ed. by Samuel A. Ashe. Greensboro: Charles L. Van Noppen, 1907. 263.

[19] Ibid., 264

[20] Ibid.

[21] Smith, Maud Thomas. “Grimes, John Bryan.” Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Vol. 2 (D-G). Ed. by William S. Powell. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

[22] Haywood, 265-6.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Haywood, 264

[25] Noble.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Grimes, J. Bryan. “The Unveiling of the Virginia-North Carolina Monument and Wyatt Memorial at Bethel, Virginia, June 10, 1905.” (North Carolina Collection, Chapel Hill). https://archive.org/details/unveilingofvirgi00grim

[29] Ibid.

[30] Long, Racheal, “Grimes Dormitory. Building Notes. Chapel Hill: Facilities Planning and Design, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1993. 151.

[31] Henderson, 236.

[32] Alcott, John V. The Campus at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill Historical Society, 1986. 66.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid., 65.

[35] Ibid., 65-6.

[36] Snider, 183.