By Aaron Chalker

Today, Hill Hall stands as a building for the learning, performance, and enjoyment of music on campus at Carolina, housing the Music Department since 1930. But the history of this structure extends far beyond merely one name and one purpose. John Sprunt Hill is the man who transformed the building, yet Andrew Carnegie is responsible for its existence and its beginning as a library. Carnegie’s namesake has all but faded away on campus at UNC, while the legacy and impact of UNC alumnus John Sprunt Hill continues.

Contemporary photo of Hill Hall. Photo courtesy of UNC Department of Music

The building is located on the McCorkle Place quad on the northern part of the main campus at UNC Chapel Hill, with Hyde Hall to its north and Person Hall to the south.

The Building’s Beginning: Carnegie Library

The building known as Hill Hall today was originally known as Carnegie Library. It all began in 1905 when Andrew Carnegie, the wealthy steel industrialist and philanthropist, offered the University $50,000 (later $55,000) for the building of a new library. The offer by Mr. Carnegie required the University to raise an endowment that matched the $55,000 gift. Numerous alumni and beneficiaries donated money for specific departments within the library, and among them was John Sprunt Hill. He contributed $5,000 for North Caroliniana books.[1] Little did Hill know that the library building would bear his name as a music building in a little over two decades time.

Carnegie Library, UNC. Photo courtesy of UNC Plan Room

Construction for the new library building began in October 1906. The building was completed in the summer of 1907, but did not open until late September 1907 due, according to President Francis P. Venable’s 1907 report, to a furniture delay.[2]

The building’s original designation as a Carnegie Library holds significant historical value that associates it with many other library buildings alike across the country. Andrew Carnegie took philanthropy to new heights with donations of over $40 million that went towards 1,679 new library buildings across the United States.[3] Carnegie used his fortune to bring knowledge and resources to cities and colleges.

Like many other Carnegie Libraries around America, this building exhibits a classical style of architecture. It exhibits features common in most Carnegie Libraries built at the time, like a large rotunda and skylight as well as multi-tiered stacks and central processing space.[4] The original architectural firm for the building was Frank P. Milburn and Company Architects of Washington D.C.[5] The firm designed a number of other buildings around the campus.[6] An example of another Carnegie Library that looks very similar to the University’s building is from Davenport, IA, built around the same time period. Take a look at the pictures below and compare the similar architecture of the Carnegie Libraries of Davenport and UNC.

Carnegie Library at UNC in 1912. Photo courtesy of UNC College of Arts & Sciences

Carnegie Library of Davenport, IA built in 1904. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

An Expanding University Must Expand Its Library

University leaders, like Librarian Louis R. Wilson and President Harry Woodburn Chase, began to recognize in the 1920s that the student body was growing and determined that a library matching that growth and size was necessary. The Carnegie Library building was said to be at capacity for books by 1923, and John Sprunt Hill, as chairman of the Trustee’s Building Committee, noted in a formal acceptance speech of Wilson Library that “in the old days” the average use of books by students was around 12, while that number had increased to 100 in 1929.[7] It was clear that something had to change to meet the demands of the university.

The following is a quote from President Chase in 1924 regarding the situation of Carnegie Library and the future of the University library:

“The present building cannot be enlarged; the problem is not one of additions to the stacks, or of the construction of a large reading room, but of the erection of a building of a quite different plan throughout, to fit the changed needs of an institution grown not only larger but vastly more complex. In short, we have a library built for, and reflecting the needs of, a small college; our need is for one to meet the conditions of work in a university.” [8]

As President Chase expressed in these words, the need for a new library at a much larger scale was crucial in expanding the university into the role of a “modern university” that supported the likes of graduate programs and world-class research.[9] A key piece of the puzzle was hosting a nationally top-tiered library. This meant that a new library was in the works, and the status of Carnegie Library as a library building was uncertain. An interesting rumor centered around the naming of Wilson Library is that Hill “would have dearly loved to have the library named for him.”[10] He would not receive that honor, but it was not long until his name was attached to a building.

The Transition from Library to Music Building: Carnegie to Hill

With the completion of Wilson Library in 1929, Carnegie Library lost its distinction as the University library. But John Sprunt Hill and the university’s Building Committee had an idea for the building’s use. Hill, who was Chairman of the Building Committee at the time, suggested that an auditorium wing be added to the building for the music department. His suggestion was accepted by the Executive Committee on September 23, 1929.[11]

With the unsafe condition of (old) Memorial Hall at the time, which is where Hill originally had intended for a new pipe organ to go, it became imperative to complete this new auditorium for the new music building in order to have an adequate performance and gathering space on campus.[12] Hill wrote to President Chase in November 1929:

“My experience at the University is that the difference between the success and failure of a building is frequently the expenditure of a very small amount of money on the interior finish, and I am clearly of the opinion that a building which is to be used by the Music Department and for public organ recitals should have its interior finished in keeping with the high purpose for which it is to be used.”

“In view of the emergency in regard to Memorial Hall, I think that every possible effort ought to be made to rush the construction of the auditorium as rapidly as possible, so that the commencement exercises next June can be held in the Music Hall auditorium.” [13]

In that same letter, Hill officially offered a gift of $43,000 to the university to go towards building the auditorium on to the new music building. In a separate letter to Chase, Hill also declared his intention to give $30,000 for a Reuter organ to go in the building.[14] The overall cost for the renovation of the building was $117,000; $73,000 of which came from Hill and his wife, Annie Watts Hill.[15] The Hill family contributed over half of the funds to transform the building into the home of the Music Department.

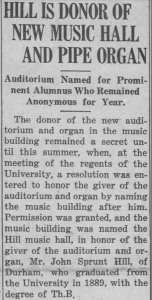

The public dedication for the completed auditorium and its Reuter organ was held on November 14, 1930. John Sprunt Hill and Annie Watts Hill attended, but the their contribution to the building’s renovation was not publicly known at the time.[16] Hill had remained anonymous for over a year. In an article from The Daily Tar Heel on September 23, 1931, Hill was recognized as the donor of the auditorium and organ for the building. The article also stated that a resolution was passed in the summer of 1931 to rename the building “Hill music hall.”[17] View an excerpt from the article on the left.

UNC Band circa 1941 in Hill Hall auditorium. Photo from the North Carolina Collection at UNC, courtesy of UNC College of Arts & Sciences

Why a Music Building?

John Sprunt Hill and the university community knew the need for performance space for the music department. But was there any particular connection between the Hill family and music? It seems that there was such a connection. The Daily Tar Heel credited the Hills with contributing “several organs to various churches throughout the state.”[18] This links the Hill family’s connection to music to their religion and church attendance. Hill himself was said to be a devout member of the Presbyterian church.[19]

The Inclusion/Exclusion of Annie Watts Hill in Hill Hall Dedication and Recognition

The numerous sources about Hill Hall and John Sprunt Hill, like newspaper articles, alumni review, and committee records, seem to disagree when it comes to Annie Watts Hill’s role in the contributions for the renovations of Carnegie Library into the eventual Hill Hall music building. Some sources, like The Daily Tar Heel article “University Recognizes John Sprunt Hill, Lawyer of Durham, as Builder,” suggest that John Sprunt Hill and his wife were both the contributors.[20] But others, like the article “Hill is Donor of New Music Hall and Pipe Organ” pictured above, name John Sprunt Hill as the sole giver.[21] This discrepancy in the rhetoric among sources raises questions that are centered around the treatment of women and their rights in the early 20th century. There is no question that John Sprunt Hill, as a powerful, wealthy white male and trustee of the University, had the largest impact on turning the building into the home of the music department. But the inclusion or exclusion of Annie Watts Hill in different sources both suggest that her name and efforts were overshadowed by her husband’s stature.

Despite the several sources that disagree on including Annie Watts Hill, one source places her at the center of attention. Letters exchanged between the Hills’ son, George Watts Hill, and Music Professor Jan Philip Schinhan in 1963 about the need to “modernize the organ” in Hill Hall sheds some light on Annie Watts Hill’s recognition in relation to the building. Professor Schinhan writes Hill that his mother gave the organ to the University, and that “it is a memorial to your mother and as such should certainly be worthy of her.”[22] This introduces a new perspective to the way the building is remembered. The words “she gave the organ to the University” have different implications than “he funded the building’s renovation.” It is these subtle differences in the way things are written and expressed that create the memory that people take away from a building like Hill Hall.

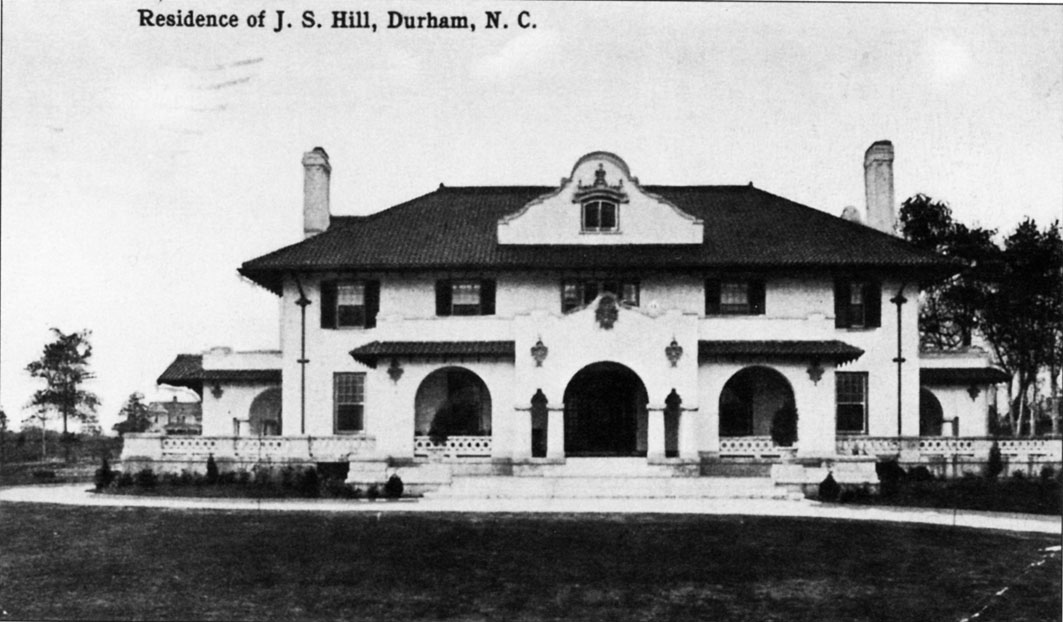

While researching Hill Hall and the life of John Sprunt Hill, little information was found regarding the life of Annie Watts Hill. The history of the John Sprunt Hill House and its application for the National Register of Historic Places reveals some pertinent information about her life. Annie Watts Hill was an active civic member in Durham, working with the YMCA, the Watts Hospital Auxiliary, and the Presbyterian Church. She died in 1940, and after John Sprunt Hill passed away in 1961, the Hill House was donated to the Annie Watts Hill Foundation for use as a meeting place for non-sectarian, non-political women’s groups. Built in 1910, the Spanish Revival style home still stands today in the Morehead Hill historic district of Durham. Today it is home to the Junior League of Durham, a women’s organization that seeks community improvement through volunteerism and civic leadership.[23] The Annie Watts Hill Foundation and the use of the Hill House for women’s civic involvement suggest that her life was dedicated to serving her community.

Hill House, 1910s-1920s. Photo courtesy of Open Durham

Hill Hall Renovations

After the transition from a library in 1930, Hill Hall saw its first renovations as the music building in 1945. The renovations added seven soundproof practice rooms in the basement of the building. This designation of the practice rooms as “soundproof” would be challenged by contemporary music students in the midst of another renovation to the building, as seen below. The building was also renovated in 1963, creating the south addition for classrooms and rehearsal space.[24]

Contemporary Controversy Surrounding Hill Hall

The most recent renovation of Hill Hall, which began in the summer of 2015 and was finished at the beginning of 2017, is at the center of controversy that has surrounded the building for decades. With a $15 million budget, the renovations added air conditioning, heat, and hot water, amenities that the building has lacked since it was built over a century ago.[25] This lack of heat/air rendered the building’s auditorium useless for months at a time. Despite this much needed addition, some music students see the renovation of the auditorium as ignoring the outdated practice rooms of the building. The auditorium received a complete makeover and an upgrade to a more modern and practical design, while practice rooms went untouched. Students say that the practice rooms are dirty and not soundproof. One student said many music majors “spend most of our time in the practice rooms,” suggesting that the renovations don’t take into account students’ needs.[26] Take a look at the video below to learn more about the recent renovations at Hill Hall. Also, click here for a visualization of how the Hill Hall auditorium has changed from its beginning in the 1930s to its modernization in 2017.

The Man Behind the Name: John Sprunt Hill (1869-1961)

The impact of John Sprunt Hill extends far beyond one building on campus at UNC Chapel Hill. Hill was a very active and accomplished individual. The list of his accomplishments and contributions to the University and the state goes on and on. Hill graduated from UNC in 1889, with Magna cum Laude honors, and also attended law school at UNC in 1891. He served as a trustee of the University beginning in 1904, and held that role for the rest of his life.[27]As mentioned above, Hill served as the Chairman of the Building Committee for the Board of Trustees, from 1923-1931.[28] He headed the committee at a time of significant growth in the physical plant of the University. In 1933, at the UNC commencement in which Hill was awarded an honorary degree, President Frank Porter Graham in his speech said that while Hill was chairman of the committee, “the University plant of a century was doubled in half a decade.”[29] This speaks of Hill’s central role in the development of the institution that we know today in Chapel Hill.

John Sprunt Hill. Photo courtesy of North Carolina Digital Collections

Hill played a major role in support of the North Carolina Collection, beginning with his donation of $5,000 for North Caroliniana while Carnegie Library was in the works. He is credited for being the founder of the North Carolina Collection.[30] In 1924, Hill built the Carolina Inn; on June 4th, 1935, Hill and his family donated the Carolina Inn to the University, under the conditions that the income from the Inn would support the North Carolina Collection.[31] Today, the Carolina Inn, still owned by UNC, carries on the wishes of Hill in supporting the North Carolina Collection.[32] Dr. H.G. Jones, the longtime curator of the North Carolina Collection, commented in 1987 that:

“John Sprunt Hill is responsible for the largest and most comprehensive state collection of published resources in the United States.” [33]

By 1957, Hill had donated over $6 million to the University over the span of his career.[34] This quote from Gordon Gray, former president of the Consolidated University of North Carolina, sums up nicely the impact of John Sprunt Hill and his love for UNC:

“Every student attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill during the past 40 years is a material witness that John Sprunt Hill has exercised a full life of love and devotion to his Alma Mater.” [35]

John Sprunt Hill: Outside of Chapel Hill

Hill had a major impact outside of the University as well. In 1892, he moved to New York City and completed his law degree at Columbia University. There, he practiced estate law and got involved with the Democratic Party. He also served in the Spanish-American War. In 1899, Hill married Annie Louise Watts. Her father was George Washington Watts, a co-founder of the American Tobacco Company in Durham.[36]

Campaign ad in newspaper for Hill. From John Sprunt Hill papers in Wilson Library (UNC). Photo by Aaron Chalker.

Not only was he active in Chapel Hill as an alumnus, but he was also active in Durham, where he resided, and throughout the state. He was a lawyer, banker, businessman, legislator, and philanthropist. After several years of marriage, Hill and his wife decided to move back to North Carolina so that Hill could go into business with George Watts in Durham. Hill made much of his money working with Watts in banking, insurance, and real estate. They went on to found the Home Savings Bank and Durham Loan & Trust Company.[37] In 1913, Hill visited Europe to study farmer cooperatives. He was known as the “Father of Rural Credits in North Carolina” for his work on the Credit Union Act of 1915, helping small farmers get lower interest rates.[38] Hill served on the North Carolina Highway Commission from 1921 to 1931. He also served as a North Carolina State Senator for the 16th State Senate District from 1933 to 1938.[39] Take a look on the right at an example of a campaign ad for Hill in a newspaper.

Hill was very involved in his hometown of Durham, and he had a large impact on the city similar to what he did on UNC’s campus. In 1933, Hill and his wife gave the City of Durham $20,000 to buy El Toro field and make it property of the city, which is where the Durham Bulls baseball team played at the time. The couple requested that the property be renamed “Durham Athletic Park,” and that no commercialized baseball was played on Sunday.[40] The DAP name stuck. The park went on to become nationally recognized for its use in the 1988 film, Bull Durham. The park still stands today, although the Bulls no longer play there. Another recreational venture of John Sprunt Hill in Durham was Hillandale Golf Course. Hill donated the course to the Durham community in 1911. The course was moved from its original location in 1960 and redesigned.[41]

Conclusion

Hill Hall is one of the many buildings on UNC’s campus with a deep, storied history. Beginning as Carnegie Library through the philanthropic efforts of Andrew Carnegie, the building carries on a physical and institutional history of Carnegie’s vast library building campaign across America. It also is a symbol of the University community and leaders’ efforts to expand the library and the scale of the campus throughout the beginning of the 20th century, one of those leaders being John Sprunt Hill. The opening of Wilson Library in 1929 further displayed the ongoing effort to bring knowledge and resources to the campus to make UNC a “modern university.” The completion of Wilson Library also served to shift the use of Carnegie Library into a music building.

Although Carnegie was the main figure responsible for the building’s existence, his impact and namesake has been overtaken by the Hill name. Hill’s contributions and efforts for UNC, Durham, and the state of North Carolina are truly remarkable. Not only does his work live on today through Hill Hall, but it also is seen with the Carolina Inn and the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library. He headed the building committee throughout the 1920s and helped to significantly increase the physical plant of the campus that is a central part of the institution of the University today. His impact is more visible to the University community when compared to Carnegie. At UNC-Chapel Hill, the long-time efforts of a local leader and decorated alumnus outshines the large-scale philanthropy of a national steel industrialist in the form of Hill Hall.

Plaque located on the front exterior of Hill Hall currently (2017). Notice there is no mention of Carnegie. Photo by Aaron Chalker

If you would like to learn more about Hill Hall or John Sprunt Hill, check out these sources:

- Hill Hall 2017 Renovations – Quinn Evans Architects

- “Hill Hall celebrates end of extensive renovations” – The Daily Tar Heel

- Celebrating 40 years: Vintage Images of Hill Hall

- John Sprunt Hill Papers, 1679-1967

[1]Louis R. Wilson, The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957), 131-132.

[2]“Records of May 1904 – September 1916,” Records of the Board of Trustees, 1789-1932 in University Archives (Oversize Volume SV-40001/11), Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[3]“Carnegie Libraries: The Future Made Bright,” National Park Service, accessed March 22, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/50carnegie/50carnegie.htm

[4]“Celebrating 40 Years: Vintage Images of Hill Hall,” College of Arts & Sciences, accessed March 22, 2017, http://college.unc.edu/2015/11/15/celebrating-40-years-vintage-images-of-hill-hall/

[5]“Hill Hall/Carnegie Hall, Original Construction,1905-1907,” Physical Plant of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1904-1963 in University Archives (Oversize Paper Folder OPF-40102/11), Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[6]“Architect Frank Milburn,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed March 23, 2017, https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/architecture/the-ymca-building–first-opene

[7]Joe A. Hewitt, “History of Wilson Library,” UNC Chapel Hill Libraries, 2004, accessed March 22, 2017, http://library.unc.edu/wilson/about/wilsonhistory/

[8]Louis R. Wilson, The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957), 384-385.

[9]Joe A. Hewitt, “History of Wilson Library,” UNC Chapel Hill Libraries, 2004, accessed March 22, 2017, http://library.unc.edu/wilson/about/wilsonhistory/

[10]Ibid.

[11]Louis R. Wilson, The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957), 397.

[12]Ibid.

[13]“University Building Committee – Minutes of Meeting, November 25, 1929,” Records of the Buildings and Grounds Committee, 1919-2002 (Series 4.4) in University Archives (Folder 297), Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[14]Ibid.

[15]Louis R. Wilson, The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957), 397.

[16]Ibid.

[17]“Hill is Donor of New Music Hall and Pipe Organ,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 23, 1931.

[18]Ibid.

[19]Archibald Henderson, John Sprunt Hill: A Biographical Sketch, New York: American Historical Society, 1937, 14.

[20]“University Recognizes John Sprunt Hill, Lawyer of Durham, as Builder,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 19, 1932.

[21]“Hill is Donor of New Music Hall and Pipe Organ,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 23, 1931.

[22]George Watts Hill papers, 1859-2000 (Box 31, Folder 417), in the Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[23]National Register of Historic Places — Nomination Form (for John Sprunt Hill House), North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, accessed April 18, 2017, http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/DH0004.pdf

[24]“Hill Hall, Addition, 1945,” Physical Plant of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1904-1963 in University Archives (Oversize Paper Folder OPF-40102/11), Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[25]Erin Wygant, “Hill Hall renovations don’t address real problems,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 1, 2016, http://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2016/02/hill-hall-renovations-dont-address-real-problems

[26]Ibid.

[27]James Vickers, The Hill Family Legacy, Chapel Hill, N.C.: General Alumni Association of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1987, 25.

[28]Roger N. Kirkman, “Hill, John Sprunt,” NCpedia, 1988, accessed on March 23, 2017, http://www.ncpedia.org/biography/hill-john-sprunt

[29]“John Sprunt Hill Praised by Graham,” George Watts Hill papers, 1859-2000 (Box 35, Folder 515) in Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[30]“University Recognizes John Sprunt Hill, Lawyer of Durham, As Builder,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 19, 1932, accessed March 23, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill-newspapers-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/image/67938939/#

[31]John Sprunt Hill papers, 1679-1967 in Southern Historical Collection (Box 07, Folder 110), Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

[32]“About the Inn,” The Carolina Inn, accessed March 25, 2017, http://www.carolinainn.com/about-historic-carolina-inn

[33]James Vickers, The Hill Family Legacy, Chapel Hill, N.C.: General Alumni Association of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1987, 26.

[34]Ibid.

[35]“John Sprunt Hill: ‘Whatever he touches he adorns,’” John Sprunt Hill papers, 1679-1967 (Box 8, Folder 131) in Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[36]“John Sprunt Hill Papers, 1679-1967,” UNC Libraries, accessed March 25, 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/03564/#d1e310

[37]Ibid.

[38]James Vickers, The Hill Family Legacy, Chapel Hill, N.C.: General Alumni Association of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1987, 25.

[39]“John Sprunt Hill Papers, 1679-1967,” UNC Libraries, accessed March 25, 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/03564/#d1e310

[40]“$20,000 Check is Received by Mayor W.F. Carr,” George Watts Hill papers, 1859-2000 (Box 35, Folder 515) in Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

[41]“About Us – Hillandale Golf Course,” Hillandale Golf Course, accessed March 25, 2017, http://hillandalegolf.com/about-us/