Jackson Hall

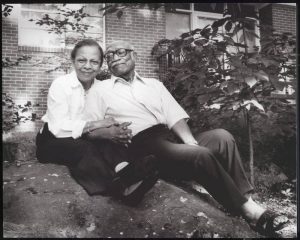

As the Admissions building for UNC-Chapel Hill, Jackson Hall is a landmark on this historic campus. Every year thousands of prospective students and their families visit this building to start campus tours or to obtain admission and scholarship information. Since this building has the important role of ushering in the new students, it is only appropriate that the building be named after Dr. Roberta Jackson and Dr. Blyden Jackson. Both of these professors taught at the university and helped many students, but especially minority students, feel welcome.

Beyond their work on campus, the Jacksons additionally played a major role in promoting African American literature and helping other African American professors reach tenured staff positions. Jackson Hall was named after the Jacksons in 1992, just over a decade after these two professors retired; however, the history of Jackson Hall goes back way before the Jacksons taught on UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus.This building has a long and interesting history.

Construction of Jackson Hall began in 1942, and was finished later that year. Located at 108 Country Club Road, this building occupies 13,896 square feet on the northern side of campus near the Playmaker’s theater, and is primarily composed of brick.[1] It was designed by the well-known architect Archie Royal Davis. The building was originally built by the U. S. Navy for its pre-flight training program. Construction of the building was rapid to meet the demand for more training space for the rapidly increasing number of naval cadets.

After the war ended, the building was given to the university in October of 1945, where it served as a meeting place for athletes with varsity letters. The Monogram Club officially moved into the building in 1948.[3] In 1957 a private dining room was added for varsity athletes. In 1972 the building was renovated for the admissions staff, which moved from Vance Hall.[4] When the Monogram Club building became Jackson Hall in 1992, the naming ceremony was well attended and the name change was well received by the students and staff.[5] In 1999, in response to a growing Admissions staff, Jackson Hall was renovated again and had some rooms expanded. Since then, it has remained mostly the same, with only minor alterations.The Navy and World War II

In 1942 the U.S. military started using public university facilities and land to train soldiers. UNC-Chapel Hill remained a naval training station until October of 1945. Most of UNC’s buildings were used for the V-12 training program that helped produce naval officers. A major component of the V-12 program was its pre-flight training, with over 25,000 men and women coming to Chapel Hill during World War II for military training.[6] The university’s enrollment dropped dramatically, but the U.S. Navy leased most of the fraternity houses and dorms on or near campus to house the soldiers. For just over two years the university was transformed by the war efforts, reflecting the national sense of pride and determination that defined America’s involvement in World War II. The navy built many new facilities for training, including pools, gyms, Jackson Hall (Navy Hall at the time), and other multipurpose facilities.

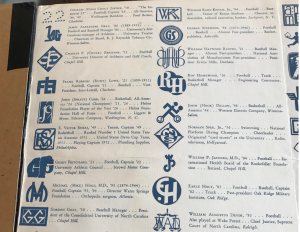

After the war ended, the U.S. military gave UNC-Chapel Hill Jackson Hall and all the other facilities it built. With lower enrollment, the Monogram Club took up residence in what was to be called the Monogram Club building. The GI Bill saw a large number of veterans come to UNC-Chapel Hill, which caused a surge in admissions numbers. The university demographics shifted as a large number of males entered the university after the war. Though the admissions numbers did level out, since then enrollment has steadily increased throughout the years. Eventually, the need for Admissions and other Administrative offices resulted in the Admissions Department slowly moving into the Monogram Club building.The Monogram Club was founded in 1938, serving both as a social and financial support network for UNC-Chapel Hill alumni and students. Originally, the Monogram Club was only for varsity athletes, most of whom went on to become professional athletes, lawyers, doctors, or some other prestigious occupation. Members of the Monogram Club had to have been star athletes, but were also required to show academic success. As of 1953, members of the Monogram Club included many popular UNC athletes, including Charles (Choo Choo) Justice, William Rand Kenan, Floyd Simmons, and many other former and current varsity athletes.[9] The Monogram Club eventually gave way to the Rams Club, which is currently housed in the Williamson Athletics Center.

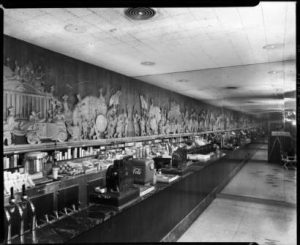

The club has always been focused on athletics; however, it is much more inclusive now and provides ticket priority and other benefits for students and alumni in return for an annual membership fee of $100. Varsity experience is no longer required. Though the name has changed, the primary purpose of the club has remained the same: to provide support for UNC’s athletes while simultaneously providing them with educational opportunities.[10] While the Monogram Club originally focused mostly on football, baseball, and basketball, it now provides funding for athletes and facilities of all twenty-eight varsity sports. The Rams Club now has 14,000 members, and has rapidly expanded from the time it could be housed in the Monogram Club Building, now Jackson Hall. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s the building served as a snack shop where students and athletes alike could grab a meal. There was also a private dining hall reserved for athletes.[11] The Circus-Soda bar was open to the students and was a popular place for students living on north campus. As the campus expanded, employees of Admissions began to take up residence in the Monogram Club Building. In 1972 the Monogram Club moved out, and the rooms became offices for the Admissions staff. The snack bar stayed for a while, but was eventually removed sometime in the 1990s.[12] Since 1992, the Admissions Department has had full control of this building.

Another fascinating aspect of the Monogram Club building is that it had a very popular wood carving called The Circus Parade. This iconic carving, almost twenty-five feet long and six feet high, depicts what its name would suggest, a circus parade with clowns, animals, and much celebration. The wood used for the carving came from a California redwood.[14] This carving helped the soda fountain earn the name Circus-Soda bar, and was a feature recognized by most students and alumni. The carving was eventually moved to the Carolina Inn. It now resides in the West Wing staircase of the George Watts Hill Alumni Center, which houses the Carolina Club and events for the Alumni Association. The Circus Parade was created by a former employee of the university named Carl Boettcher. Boettcher was originally from Pomerania, but he and his wife moved to the United States after World War I.[15] Carl worked for the university in restoration and repairs for six years before his talent for wood carving was noticed. Around 1947 he carved The Circus Parade for the Monogram Club building, later going on to carve the university seals in buildings such as the Forest Theater, the South Building, and the Bowman Gray Swimming Center. Boettcher also did important wood-working for the Morehead Planetarium.[16] Boettcher is just one of the many unsung heroes in the history of UNC-Chapel Hill, as his work has been admired by several generations of students, alumni, and faculty over the last seventy years.

Admissions

The function of Jackson Hall has changed dramatically since its days as a social area for the Monogram Club. It is now arguably the most important building on campus. Most of the staff and equipment needed for making important admissions decisions are housed in Jackson Hall. It became the admissions building largely in response to a rapidly growing student body. As the “Baby Boomer” generation began applying for college in the 1970s, there was a need for more resources and employees, and these extra personnel were placed in Jackson Hall, thus cementing it as the home of Admissions. Just last year the Admissions Department had to make decisions on 35,875 applicants. 4,228 of those applicants were enrolled at UNC-Chapel Hill.[18] Besides handling the massive amount of information involved with the new student admission process, Jackson Hall also serves as the meeting site of UNC’s campus tours for prospective students and their families. Thousands of visitors come visit Jackson Hall every year to learn more about the application process.

Naming Ceremony

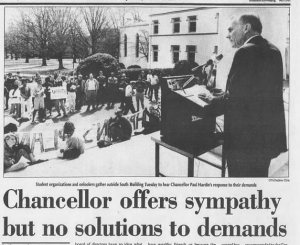

A building housing a department as important as admissions needs to be named after someone equally important. That is why then Chancellor Paul Hardin said “I do not have to tell any of their friends or family how richly this honor is deserved by Blyden and Roberta. They have had distinguished careers on the faculty here, and both were pioneers of dignity and strength in the diversification of the UNC faculty” at the Jackson Hall naming ceremony in 1992.[20] The ceremony was well attended, and there was much support by the faculty. The Jacksons were clearly important, and to understand the significance of this name change one must explore the careers and lives of Blyden and Roberta Jackson. Though no one protested the naming of Jackson Hall, this renaming did occur in the midst of controversy on campus. Paul Hardin was under a lot of pressure to build a new building to house the Black Cultural Center.[21] At the same time, the university was facing a discrimination suit involving a campus police officer. Due to the surrounding controversy, some members of the UNC community felt that the renaming of Jackson Hall was an attempt to mitigate the racial tensions on campus; however, the majority of the community saw this as well-earned recognition for two influential faculty.

Roberta Jackson was born in Germantown, NC in 1920. She spent some of her childhood in North Carolina, and some of it in West Virginia.[23] Though Roberta’s parents encouraged her learning and ensured she got an education, Roberta still had to face the socioeconomic and racial barriers of the 1930s and 1940s. Despite these obstacles, Roberta excelled in school, graduating high school as the valedictorian. Roberta went on to get her bachelor’s at Bluefield State College, her Master’s at Ohio State, and her doctorate in education from New York University.

After getting her doctorate, Roberta worked at Southern University in Louisiana, while also working on getting minority women better education opportunities, and ultimately better occupational opportunities.[24] “Career Education: A Concept for Minorities?” and “Some Implications for Career Education” are just two of many articles written by Dr. Roberta Jackson to address the difficulties that minorities face when trying to achieve higher education.[25] Dr. Jackson also pushed for the improvement of high school programs that provide help for low-income students. While Dr. Jackson focused much of her attention on helping the historically disenfranchised students, she also emphasized the importance of education for everyone by saying, “career education may serve substantially the needs of all persons regardless of sex, age, creed, race or socioeconomic status.[26]” With these beliefs, and a passion for helping students succeed in school and in life, Dr. Roberta Jackson was a clear fit for an academic institution such as UNC-Chapel Hill.

Dr. Jackson joined the university in 1970, and worked in academic affairs until she retired in 1981.[27] During her time at the university, Dr. Jackson helped many minority students feel at home, and helped them navigate the college experience. Many of these students were first-generation college students who didn’t have the support that some of their peers did. Dr. Jackson was also the first African American woman to earn tenure at the university. She would have been the first African American to earn tenure had it not been for her husband. Dr. Jackson went on to help bring African American scholars into the UNC faculty, and helped them earn tenure as well. Over a decade of helping UNC students achieve their goals was more than enough to earn Dr. Jackson the honor of having a building named after her; however, she also served on many national committees and groups dedicated to improving the lives of minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged children. Dr. Jackson was an executive member of the Children’s Home Society of NC, was part of a child development group at the 12th International Congress of Family Life, and served on the board of directors for the Day Care and Child Development Council of America Incorporated. Dr. Jackson was involved with many other groups, so these are just a few examples on how she important and impactful she was internationally. She won the 1972 Arthur S. Flemming and Patricia Nixon Citation for Service to Project FIND and the 1977 Outstanding Contribution to Children and Families of America Award, among many other awards throughout her career.[28] By the time of her retirement, Dr. Roberta Jackson was known by her fellow faculty as one of the most significant faculty members in the school’s history. Roberta Jackson passed away in 1999, and the growing success of current minority students, along with the movements they support, are largely indebted to the work and passion that Dr. Roberta Jackson displayed during her time at UNC-Chapel Hill.

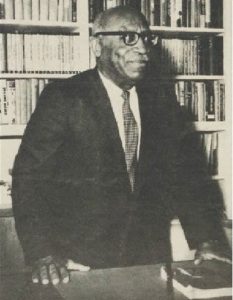

Blyden Jackson was born in 1910 in Louisville, Kentucky. Blyden’s parents, like Roberta’s, encouraged his learning and made sure he received the best education possible for an African American in the South[30]. Kentucky was deeply segregated during Jackson’s childhood, and Jackson faced the difficulties of being socioeconomically disadvantaged. Jackson once said, reflecting back on his childhood, that “I knew that there were two Louisvilles…and two Americas. I knew, also, which of the two Americas was mine. I knew there were things I was not supposed to do, honors I was not supposed to seek, people with whom I could have been congenial to whom I was never supposed to speak, and even thoughts I could have harbored that I was never supposed to think. I was a negro.[31]” Despite obvious racial obstacles, Blyden Jackson thrived in school, and went on to get his bachelor’s degree at Wilberforce University in Ohio. Jackson then spent over a decade working at a public junior high school before going to the University of Michigan to get his master’s and doctorate. Doctor Jackson then went on to teach at Fisk University for nine years before accepting a position as department head of the English department at Southern University in Louisiana.

Besides teaching, Jackson wrote many very important articles and books about the advancement of African American literature in American education. Blyden Jackson’s 1955 article “The Case for American Negro Literature” was extremely important for getting African American literature into public school libraries to help expand the views and cultural awareness of the students. Other famous works by Dr. Jackson include: “The Waiting Years,” “Black Poetry in America,” and “Largo for Adonais.[32]” These works largely discuss the stereotypes surrounding African American culture, and how these stereotypes have hindered the development of African American Literature in America.[33] Jackson’s efforts to get African American literature into schools has helped many students learn more about different cultures and histories and not feel isolated by a world of white, highly-biased literature. Many of Jackson’s writings fall under the genre of criticism, as they analyze cultural bias in both white and black writings.

Dr. Jackson also donated a lot of his time to organizations involved with improving education. Dr. Jackson served as the both the vice president and president of the College Language Association (vice-president, 1955-57; president, 1957-59), served on the National Council of Teachers of English, the Modern Language Association of America, the College English Association, the North Carolina Council of Teachers of English, and served as the president of the Louisville Association of Teachers in Colored Schools.[34] His work in the U.S. education system is well documented, and many current students enjoy better public education because of the hard work of Dr. Jackson and others like him.

Dr. Jackson came to UNC in 1969, where he was a member of the English Department until his retirement in 1981. Dr. Jackson served as the associate dean of the English graduate school from 1973-1981.[35] As a professor at UNC, Dr. Jackson was instrumental in bringing in African American literature into the department, and helped to expand and enrich the education of the students he taught[36]. After his retirement in 1981, Dr. Jackson remained in Chapel Hill until he passed away on May 1, 2000. With all the work that Dr. Roberta Jackson and Dr. Blyden Jackson put into UNC-Chapel Hill, and into the public education system as a whole, the faculty and administration agreed that no one was more deserving to have a building named after them than these revolutionary scholars.

While Jackson Hall is relatively new to UNC-Chapel Hill, which was chartered in 1789, this building has a unique and fascinating history that reflects the events and trends that UNC-Chapel Hill has experienced. Originally constructed for military purposes, this building became the Monogram Club building in a time of peace and relatively prosperity in the late 1940s and 1950s. As the university grew, this building became less of a social center and more of an administrative building to help organize the growing student body. Eventually, the Monogram Club building earned the name Jackson Hall after Dr. Blyden Jackson and Dr. Roberta Jackson. Naming this building after the Jacksons is a way of recognizing the hard work of these professors who set the foundation for many new departments and movements that strive to bring equality and new perspectives to the U.S. education system. To this day, Jackson Hall serves not only as an admissions center, but also as a historic site and a tribute to the hard work of the Jacksons.Additional Information

If you are interested in learning more about the history of Jackson Hall, or the history of the UNC-Chapel Hill campus as a whole, the university archives have many resources that detail the many unique aspects of the university history. I would also recommend to anyone interested that they read some of the articles and books written by Dr. Roberta Jackson or Dr. Blyden Jackson. These works provide an interesting insight into how African American literature and history should and can become a part of public education, and how this can greatly reduce the prevalence of racism and bigotry in the United States. “Blyden Jackson, Humanist” is an interesting piece written by Robert Bone that provides some background information about Dr. Blyden Jackson, and how his background influenced his writings. The UNC General Alumni Association has information about many historic items of importance to the university, including information about The Circus Parade carving. I encourage anyone who is interested in UNC-Chapel Hill history stop by the George Watts Hill Alumni Center, which was very helpful for me in my research.

[1] Carolina. July 14, 1999. Retired education professor Dr. Roberta Jackson, for whom UNC-CH’s Jackson Hall is named, dies at 79. News. 428

[2]http://mw2.google.com/mw-panoramio/photos/medium/18354219.jpg

[3] The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2017. Aliases and Notes for Jackson Hall (153). Plan Room: 1.

[4] The Carolina Story. March 11, 2017. Blyden (1910-2000) and Roberta Jackson (1920-1999) and Jackson Hall. A Virtual Museum of University History 1.

[5] The Carolina Story. March 20, 2017. Navy Pre-Flight Cadets. A Virtual Museum of University History. 1.

[6] The Carolina Story. March 20, 2017. Navy Pre-Flight Cadets. A Virtual Museum of University History. 1.

[7] The Carolina Story. March 20, 2017. Navy Pre-Flight Cadets. A Virtual Museum of University History. 1.

[8] The Carolina Story. March 20, 2017. Navy Pre-Flight Cadets. A Virtual Museum of University History. 1.

[9] The University of North Carolina Monogram Club. 1952. Monogram Club

[10] The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2017. Aliases and Notes for Jackson Hall (153). Plan Room: 1.

[11] The University of North Carolina Monogram Club. 1952. Monogram Club.

[12] Edy, Carolyn. 1997. Etched in History. UNC General Alumni Association. 1.

[13] http://i.ebayimg.com/11/!BQWjBw!BWk~$(KGrHgoOKi0EjlLmWv+IBJ4gLC0Sow~~_35.JPG?set_id=8800005007

[14] Edy, Carolyn. 1997. Etched in History. UNC General Alumni Association. 1.

[15] Edy, Carolyn. 1997. Etched in History. UNC General Alumni Association. 1.

[16] Edy, Carolyn. 1997. Etched in History. UNC General Alumni Association. 1.

[17] Morton, Hugh M. 1950s. Monogram Club, UNC-Chapel Hill. Hugh Morton Collection of Photographs and Film

[18] UNC General Alumni Association. 2017. Fine OK’d After Carolina Exceeds Admissions Cap for Second Straight Year. Carolina Alumni Review

[19] UNC General Alumni Association. 2017. Fine OK’d After Carolina Exceeds Admissions Cap for Second Straight Year. Carolina Alumni Review

[20] Carolina. July 14, 1999. Retired education professor Dr. Roberta Jackson, for whom UNC-CH’s Jackson Hall is named, dies at 79. News. 428

[21] University Archives and Records Management Services. 1992. Student Protests in Support of the Black Cultural Center, 1992. For the Record. 1.

[22] University Archives and Records Management Services. 1992. Student Protests in Support of the Black Cultural Center, 1992. For the Record. 1.

[23] Jackson, Roberta H. 1976. Career education: A concept of minorities. The High School Journal 60 (2): 92.

[24] Chapel of the Cross. 1999. Mass of Christian burial: Roberta Bowles Hodges Jackson, Ph.D., 23 February 1920-11 July 1999.

[25] Carolina. July 14, 1999. Retired education professor Dr. Roberta Jackson, for whom UNC-CH’s Jackson Hall is named, dies at 79. News. 428

[26] Jackson, Roberta H. 1976. Career education: A concept of minorities. The High School Journal 60 (2): 92.

[27] Carolina. July 14, 1999. Retired education professor Dr. Roberta Jackson, for whom UNC-CH’s Jackson Hall is named, dies at 79. News. 428

[28] Chapel of the Cross. 1999. Mass of Christian burial: Roberta Bowles Hodges Jackson, Ph.D., 23 February 1920-11 July 1999.

[29] The Carolina Story. March 11, 2017. Blyden (1910-2000) and Roberta Jackson (1920-1999) and Jackson Hall. A Virtual Museum of University History 1.

[30] Rubin, LD. 2000. Blyden jackson: A memory. Cla Journal-College Language Association 44 (1): 133-9.

[31] Bone, Robert. 1978. Blyden jackson, humanist. Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Culture 31 (4): 623-30.

[32] Margolies, Edward. 1992. “black literary history”. essay-review of A history of afro-american literature, volume 1: The long beginning, 1746-1895, by blyden jackson. Mississippi Quarterly 45 (1): 105.

[33] Miller, R. Baxter. 1984. The wasteland and the flower: Through blyden jackson: A revised theory for black southern literature. Southern Literary Journal 17 (1): 3.

[34] Bone, Robert. 1978. Blyden jackson, humanist. Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Culture 31 (4): 623-30.

[35] Bone, Robert. 1978. Blyden jackson, humanist. Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Culture 31 (4): 623-30.

[36] Jackson, Blyden. 1989. The History of Afro-American Literature. volume 1.

[37] News and Observer. 1970s. Blyden (1910-2000) and Roberta Jackson (1920-1999) and Jackson Hall. UNC Chapel Hill Facilities Services.

[38] The Carolina Club and the General Alumni Association

![Jackson Hall from the Country Club Road[2]](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2017/04/jh-300x194.jpg)

![Cadets on campus in 1944[7]](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2017/04/cadets-3-300x298.jpg)

![Pre-flight training at UNC Chapel Hill[8]](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2017/04/r-300x219.png)

![Charlie (Choo Choo) Justice[13]](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2017/04/choo-241x300.jpg)

![Modern photo of Jackson Hall[19]](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2017/04/jackson-hall-300x134.jpg)