A Longer (Tar Heel) Table: The Long History of Lenoir Dining Hall and Campus Food

By: KC Hysmith

Jennifer Krause, “Lenoir Hall, completed 1940,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History.

The University commissioned the building of Lenoir Hall in 1939 using funds from the New Deal’s Public Works Administration.[1] The Board of Trustees chose to honor General William Lenoir, the first chairman of the University’s board of trustees, in naming the new dining hall. It has been a dining hall for the entirety of its existence, offering students, faculty, and staff various meal options and spaces to gather. To satisfy a growing University, Carolina Dining Services now includes three main dining halls (Lenoir, Brinkhous-Bullitt Building: The Beach Cafe, and Kenan-Flagler Business School: McColl Cafe) as well as numerous satellite cafes, small food markets, and coffee shops situated throughout campus. Today, Lenoir Dining Hall remains the flagship of Carolina Dining Services, overseen by an Executive Chef and staffed by a variety of culinary team members including students.[2]

Like many other buildings on this campus, the University named Lenoir Dining Hall after a white male southerner with a problematic past. While many other buildings have faced scrutiny for such namings, Lenoir has been overlooked, likely because it has been the center of other much more contemporary campus controversies during its relatively short existence. What is most intriguing about Lenoir Dining Hall, however, is not its namesake, though it is definitely no small issue, but rather the civic engagement fostered between students, staff, and faculty over the universal issue of food. Throughout its history, Lenoir Dining Hall has been a setting for campus social life, serving as both a battleground for social justice and a space for community empowerment and building longer tables.

DINING BEFORE LENOIR

Frances Jones Hooper, “Silhouette of the Campus of the University of North Carolina,” Documenting the American South, Louis and Mildred Graves Papers (#4010).

Long before Lenoir Hall served hungry Tar Heels, several buildings were used as the University’s primary dining hall. When the University first opened in 1795, most students boarded, socialized and dined at a single building called Steward’s Hall. Commissioned in 1793 with several other first buildings on campus, Steward’s quickly gained an unsavory reputation. Reportedly, the food was so bad that students revolted in 1799 and stoned the building:

“Having borne with patience for a considerable time a failure of the Steward to comply with the bill of fare, and having observed the inefficiency of individual complaints to produce an amendment, and seeing that our rights are infringed upon, we have thought proper to petition the Faculty, in whom is vested the power to enforce a compliance. Our grievances are daily accumulated, and they are such whose importance demands immediate redress. We have long observed an insufficiency of butter.–The beef has been such as to shock every sentiment of decency–frequently unsound and covered with vermin.–The frequency of this shows that it proceeds from carelessness in the Steward, and as such we require an alteration.”[3]

“James Patterson’s Proposals for the Steward’s House, 1793.” Documenting the American South.

Steward’s Hall, a wooden building made with lumber from nearby felled trees, once stood north of the present day Carr building.[4] The builder, James Patterson, designed a building “thirty-six by thirty feet, with two brick chimneys, a kitchen with a brick floor, and three other rooms.”[5] One of these other rooms became the dining room and the remaining two were occupied by student boarders. Steward’s Hall fell out of use by 1816 and the University later dismantled the building in 1847 after operating as a “private boarding house for a number of years.”[6]

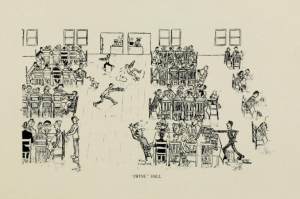

“Swine Hall” cartoon, University of North Carolina, Yackety yack, 1916, Digital NC, North Carolina College and University Yearbooks.

As the University grew, other buildings housed and managed student dining services. In 1898, the University rebuilt the gymnasium to become Commons Hall, which served as the University’s dining hall for over another decade.[7] Built on the former site of the first President’s House, Swain Hall, built in 1913, replaced Commons Hall, and opened its doors in 1914.[8] The new building doubled the capacity of the former dining hall and accommodated 500 diners.

Despite the improvements, Swain Hall gained its own unfortunate reputation with an indecorous nickname to match: “students then called it Swine Hall, an unflattering comment on the quality of the food and the deportment of the diners.”[9] The University’s unintended tradition of poorly received dining halls and bad cafeteria food endured until the construction of Lenoir. According to reports, the food improved, although students subsequently redirected their scrutiny to other facets of the dining hall.

THE NAMESAKE

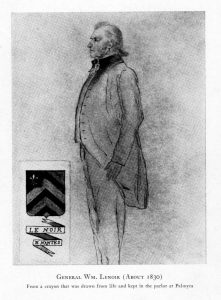

“William Lenoir (1751-1839),” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History.

William Lenoir was born in Brunswick County, Virginia on May 8, 1751. His father sold the family’s plantation and moved the family to Edgecombe County, North Carolina in pursuit of richer farmland. Educated as a teacher, Lenoir opened elementary schools in Brunswick and Halifax Counties. After he married Ann Ballard of Halifax County in 1771, Lenoir quickly realized that he could no longer support his young family on a teacher’s salary and chose to pursue the more financially lucrative profession of surveying. After an apprenticeship, William Lenoir moved his family to the North Carolina frontier just prior to the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775. Lenoir first settled in Fisher’s Creek (present day Wilkesboro) and later moved to Happy Valley on Buffalo Creek (near the present day town of Lenoir). In 1792, Lenoir and his family finished construction on their mansion called Fort Defiance, where he spent the remainder of his life.

When the Revolutionary War began, Lenoir enrolled in the local militia, but his leadership skills quickly allowed him to climb ranks to the position of Captain and later General. After the war, Lenoir served as a member of the state legislature, representing Wilkes County from 1781 to 1795.[10] He also served as the speaker of the North Carolina Senate for five years. In November of 1790, the University appointed a committee to “form a device for the common seal of the University.”[11] Lenoir led the committee as president and worked alongside other notable North Carolinians including John Hay, Stephen Cabarrus, and Adlai Osborne to form the first board of trustees of the University of North Carolina.

Like numerous other founding members of the University, Lenoir owned slaves. According to University historian John “Yonni” K. Chapman:

“In July 1790, trustee William Lenoir purchased an eleven year-old slave named Martin. In the bill of sale, the seller guaranteed the “said Negroe Boy to be healthy and sound & clear of all infirmity.” The young man might as well have been a mule. On March 16, 1844, Lucy Battle wrote to her husband, William H. Battle, a university professor and trustee, “. . . by the way_ you own another negro. Sue wrote that China has a fine daughter. . . your property is increasing rapidly.”[12]

Little else is known about his slaves, who they were, or what became of them after his death. And while Lenoir’s problematic past does not contain, at least on public record, the same number or descriptively shocking sort of atrocities as those attributed to other commemorated names carved into the faces of buildings around campus, it is nonetheless an issue, albeit one typically overlooked due to the other contemporary controversies concerning Lenoir Dining Hall. Though Lenoir’s legacy is not the focus of this campus narrative, this report aims to be clear in its expansive history and highlight his inhumane actions. The name Lenoir remains on the face of the campus’ main dining hall and, though it is never explicitly mentioned in student accounts, seems to serve as an provoking invitation and a physical platform for activism in the name of civil justice.

OCCUPATION DINING HALL

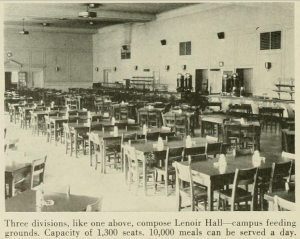

Through the New Deal Era Public Works Administration, the Federal Government helped fund the erection and renovation of numerous buildings including Lenoir Dining Hall. The new dining hall, which could accommodate 1,300, was commissioned in 1939 and eventually opened to hungry diners in January of 1940.[13]

An empty dining room, University of North Carolina, Yackety yack, 1950, Digital NC, North Carolina College and University Yearbooks.

Shortly after its construction, World War II broke out in Europe. In response, the U.S. Navy created “four new preflight centers for the training of naval pilots” and chose to place one at Chapel Hill largely due to the nearby local airport owned at that time by the University.[14] That same year, the University established a naval reserve officer training program (ROTC).[15] This placement changed the face and feel of campus dramatically, adding thousands of new students and piling pressure on an already stretched-thin University. To keep up with this new demand, Lenoir Dining Hall was rearranged to accommodate these new diners much to the chagrin of non-naval students.[16]

Contention between the traditional academic and naval trainee students intensified during their tenure on campus, and these frustrations were focused around the dining hall. In July of 1942, the Daily Tar Heel ran a piece entitled “Cafeteria Enlargement Predicted” and claimed that the University planned to convert the basement of Lenoir Dining Hall into a “separate and distinct” luncheonette in an effort “to ease the growing strain on University eating establishments.”[17] In another irksome move, the University considered reopening the abhorred Swain Hall as a temporary cafeteria to help feed the new mass of naval cadets.[18] Writing in another issue of the Daily Tar Heel, student correspondant Billy Webb explained that “contrary to previous announcements Lenoir hall will be completely allocated to Navy use, having proven incapable of combined student and Pre-Flight school capacity. The reason for the unforeseen strain upon Lenoir facilities is that cadets eat two and one-half times as much food per meal as a normal student.”[19] This closure forced students to seek their meals at establishments near campus such as those along Franklin Street. To make matters worse, students reported subsequent price hikes by these same retailers.[20]

Even when Lenoir Dining Hall was open, students found some of the more foundational changes difficult to stomach. One such change was a direct result of the wartime worker shortage, which forced (or rather allowed) women to fill previously male-dominated jobs including waiting on tables in the dining hall. Another Daily Tar Heel writer, Hazel Katherine Hill, covered the switch in her article, “Coeds Take Over Positions in Navy Lenoir Dining Hall: Women Replace Men in Essential Work.”[21] Women were not the only new employees; the same wartime shortage provisioned the University to hire German prisoners of war as waiters to help maintain the “very high standard” of the dining hall. The prisoners caused quite a stir on campus. Reports in the August issues of the Daily Tar Heel offered dueling opinions on the new wait staff. Some were optimistic and offered upbeat portraits of prisoners “laughing and talking” and overcome with a “profound change.”[22] Others objected this vision and argued that the prisoners, or “Nazi” as indicated in the article title, were “arrogant and conceited.”[23] Little evidence exists suggesting any meaningful engagement between the students and the prisoners, but their presence was clearly noted and undoubtedly added yet another problematic layer to the dining system on campus.

FOOD FIGHT

“It isn’t slavery time anymore…” – Elizabeth Brooks

Throughout the 1960s, the University went through another round of fundamental changes, chiefly due to the slow integration of African American students and faculty into campus life. Desegregation efforts occurred throughout campus, including Lenoir Dining Hall. Despite this University-wide mandate, discriminatory practices against African Americans on campus continued. This unfair treatment was especially problematic for the predominately African American staff and service personnel.[24]

In the fall of 1968, Carolina Dining Services foodworkers suffered from all manner of grievances, including unfair and no overtime pay, inaccurate job classifications, and inhospitable working conditions. A group of employees sent a list of suggestions to the “Employer of Lenoir Dining Hall” to help improve employer-employee work relationships. Shortly after, the University laid off ten employees and blamed the terminations on the severe drought that had forced the “suspension of dishwashing operations in Lenoir.”[25]

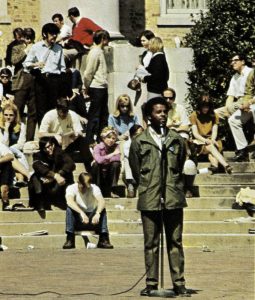

“Students Support the Food Workers,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History.

The foodworkers then turned to the students for help. The disenfranchised foodworkers teamed up with the newly formed Black Student Movement who presented then Chancellor J. Carlyle Sitterson with a list of 23 demands, including immediate attention for the “intolerable working conditions of the Black non-academic employees.”[26] Unsatisfied with the Chancellor’s response and the University’s refusal to meet to discuss their grievances, a small group of foodworkers and the leading members of the Black Student Movement considered their next steps.

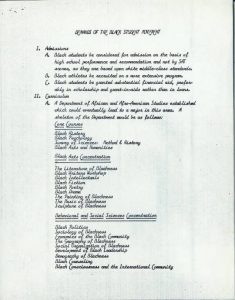

“The BSM’s 23 Demands: December 1968,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History.

On Sunday, February 23, 1969, the foodworkers arrived for their shifts at Lenoir Dining Hall and set up their serving lines. When the cafeteria doors opened, the foodworkers walked out from their lines and sat down at the cafeteria tables. Despite attempts from the supervising staff, the sit-in continued. The following day, “nearly 100 dining hall employees refused to report to work.”[27]

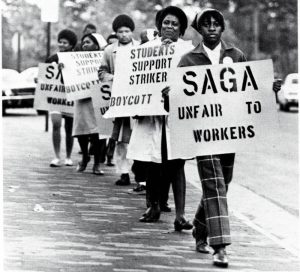

The University did not pursue negotiations, largely because the administrators disliked the connection between the student-led Black Student Movement and the foodworkers. To the administration, this connection labeled the strike as a “student uprising” rather than a legitimate workers issue. The University’s silence frustrated Preston Dobbins, the founder of the Black Student Movement, who quickly mobilized several hundred students to protest in support of the food workers by banging trays on counters. Additional protest tactics included picketing outside of Lenoir Hall, additional sit-ins, calls for boycotts, and even the takeover of the foodworkers serving lines resulting in a purposeful slow-down of food distribution.[28]

“Lenoir Hall surrounded by police and protesters,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History.

In early March, these tactics turned hostile as members of the Black Student Movement overturned tables and chairs, shouted, and shoved other students. The University closed Lenoir. Then Governor Robert W. Scott threatened to send nearby National Guard units and “squads of riot-trained Highway Patrol” in order to ensure that Lenoir Dining Hall would open for breakfast later that week. In response to these threats, both faculty and students, black and white, mobilized to help the foodworkers’ efforts.[29]

The strike ended on March 21 when the University paid the workers $180,000 in back pay, raised food workers’ hourly wage from $1.60 to $1.80 per hour, and appointed a black supervisor.[30] This incident also spurred the formation of the Non-Academic Employees Union, which lived on to protect the rights of numerous other University workers in the years to come.

A few weeks after the first strike, another issue emerged when the University signed over management of the campus dining services to a company called SAGA Food Services.[31] SAGA backtracked on promises to maintain the same pay and benefits for current foodworkers and laid off numerous temporary and part-time employees. In November of 1969, about 250 dining hall workers, over 90% of the total staff, decided to strike against SAGA. This second strike ended on December 9, 1969, after African American students from across the state threatened to meet for a mass protest in a show of support for the foodworkers.[32]

“Second Food Workers’ Strike: November and December 1969,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History.

Disputes concerning fair and safe labor practices continued between the University and the foodworkers for many years. However, these two initial strikes helped establish a long legacy of mobilization and activism on campus and certified Lenoir Dining Hall as a platform for civil rights.

This legacy endures through the work of several University scholars including the late John “Yonni” Chapman’s dissertation which includes a chapter commemorating the dining hall cafeteria workers’ strike of 1969. Women Behind the Lines, a documentary style video filmed in 1990, provides an overview of the food service strikes and includes interviews with two of the active strikers, Mary Smith and Elizabeth Brooks. Though the working conditions have improved, these historical works help preserve the memory of collaborative activism on campus and provide helpful precedent for future mobilization should the need arise.

“We had decided we would form a picket line because see, the Lenoir Hall -this was just the Pine Room group- and Lenoir Hall was one of the largest dining rooms. And the folk that worked in there was off on that Sunday, but they would be coming in on a Monday at 5:00 to open up. So the black students and there were lots of white students also, and we decided that we would start the picket line going the next morning at 5:00 in hopes to get to the workers before they got in to open up the Lenoir Hall.”

– Elizabeth Brooks

In 2017, Sydney Lopez and Liv Linn, undergraduate interns at the Southern Oral History Program, conducted an extensive multimodal documentary on the “UNC Foodworkers’ Strikes of 1969,” resulting in a digital exhibit and a 45-minute podcast-style documentary called The Ladies in the Pine Room.[33] The exhibit uses storymapping, audio clips, and archival documents and images to narrate the complex history of some of the most underrepresented members of the University.

LENOIR DESIGNED (AND REDESIGNED)

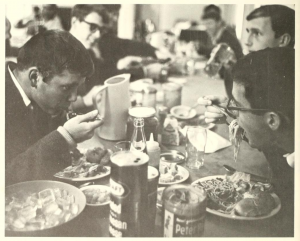

“Boys eating in Lenoir,” University of North Carolina, Yackety yack, 1967, Digital NC, North Carolina College and University Yearbooks.

Since opening in the spring of 1940, Lenoir has undergone numerous renovations and redesigns. Some of these renovations resulted from fundamental campus changes, such as the arrival of WWII naval cadets, but others were implemented simply to foster a sense of community and create “a good place to promote student-faculty interaction outside of the classroom.”[34] In 1984, major renovations included three dining rooms on the first floor, including the Central Dining Room, which seated 300, and “ran the length of the west side of the building” with “two smaller dining rooms at the northeast and southeast corners of the building.”[35] The North Dining Room, which seated over 200, was available to groups for private dinners and events and had a moveable partition for dividing or opening the room. On the other end, the South Dining Room seated only 140 and was styled more formally “like a nice hotel dining room” with linen table cloths and upholstered chairs.[36] According to a report in The Daily Tar Heel, the entire renovation of the Lenoir Dining Hall cost over $3 million.

In 2011, the University spent another $5 million to renovate and improve seating areas “in an attempt to reduce crowds” at mealtime rushes.[37] With plans to add about 200 additional seats to the “top of the heavily trafficked dining hall,” the university placed two heated tents outside of Lenoir to compensate for lost seats during construction.[38] In addition to the space, the Carolina Dining Services worked to incorporate more healthy, local, and organic food options.

CONCLUSION

“Food Lines,” University of North Carolina, Yackety yack, 1962, Digital NC, North Carolina College and University Yearbooks.

Since the Foodworkers’ Strikes of the 1960s, Lenoir Dining Hall has served as platform for public protests and a space to foster community dialogue. In 2005, a small group of students held a demonstration in support of Vel Dowdy, a Lenoir Dining Hall cashier accused of embezzlement. Students protested on her behalf as they believed she was wrongly arrested for her support of unionization.[39] Later in the fall of 2016, after national news coverage concerning the death of several African Americans at the hands of law enforcement, protesters against police brutality staged a “die-in” in Lenoir Dining Hall.[40]

Carolina Dining Services and the Black Student Movement co-hosted a themed dinner to celebrate Black History Month at Lenoir Dining Hall in 2015. The theme, “A Century of Black Life, History and Culture” included a range of foods from President Obama’s favorite pizza to historical recipes from the Harlem Renaissance jazz clubs.[41] The foods, each paired with placards indicating their significance, were chosen to help start conversations about the importance of black history.

In the fall of 2017, after demanding the removal of the Silent Sam statue, a controversial Confederate monument erected on McCorkle Place in 1913, students organized a boycott of the Carolina Dining Services including meals at Lenoir Dining Hall. Student organizers mobilized through various social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter and encouraged other students, staff, and faculty to abstain from spending any money at University-run establishments for one month. To help feed participating students, the boycott organizers coordinated with various community food establishments to arrange meal donations and solicited local restaurants to sell a limited menu at a reduced rate in a rotating pop-up shop in front of the Campus Y. At this date, little is known about the efficacy of the boycott and whether or not it influenced the University to reconsider its stance on the controversial statue. Regardless of the success of the boycott, the lines at Lenoir Dining Hall remained long and the hunt for table space during the lunch rush hour endured.

Further Reading:

Lopez, Sydney and Liv Linn. “UNC Foodworkers’ Strikes of 1969.” Southern Oral History Program digital exhibit.

Lopez, Sydney and Liv Linn. “The Ladies in the Pine Room.” Southern Oral History Program podcast audio, 2017.

Rivard, Courtney. “Lenoir Dining Hall,” Navigating Food at UNC – Digitally Mapping Foodway.

Weiner, Terry S. “Sources of Student Activism.” Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina, 1972.

Williams, J. Derek. “It Wasn’t Slavery Time Anymore: Foodworkers’ Strike at Chapel Hill, Spring 1969.” Master’s Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1979.

Works Cited:

[1] “Meeting of the Committee, February 5, 1936,” Records of the Buildings and Grounds Committee, 1919-2002, Faculty Council, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[2] “Culinary Program,” Carolina Dining Services, December 3, 2017.

[3] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina.

Volume I: From its Beginning to the Death of President Swain, 1789-1868, Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1907.

[4] Louis Round Wilson, Historical Sketches, Durham, NC: Moore Publishing Company, 1976: 83.

[5] William S. Powell, The First State University: A Pictorial History of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 1992: 15

[6] Powell, The First State University, 15.

[7] Powell, The First State University, 115.

[8] Wilson, Historical Sketches, 34.

Powell, The First State University, 150.

[9] Marguerite Schumann, The First State University: A Walking Guide, Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 1985: 46.

[10] “History of Fort Defiance,” Fort Defiance, Home of General William Lenoir.

[11] Wilson, Historical Sketches, 50.

[12] John K. Chapman, “Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960,” PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina, 2006: 26-27.

[13] Jennifer Krause, “Lenoir Hall, completed 1940,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History.

[14] “National Defense Navy: Commissioning/Decommissioning, 1943-1946” in Office of the Vice President for Finance of the University of North Carolina (System) Records, University Archives, Wilson Library.

[15] “National Defense Navy: Commissioning/Decommissioning, 1943-1946.”

[16] Billy Webb, “New Unit to Open for Fall Quarter: Action to Solve Eating Problem; Lenoir Allocated for Navy Use,” The Daily Tar Heel, Tuesday, July 28, 1942.

[17] “Cafeteria Enlargement Predicted,” The Daily Tar Heel, Friday, July 03, 1942.

[18] Webb, “Lenoir Allocated for Navy Use,” The Daily Tar Heel, 1942.

[19] Webb, “Lenoir Allocated for Navy Use,” The Daily Tar Heel, 1942.

[20] Webb, “Lenoir Allocated for Navy Use,” The Daily Tar Heel, 1942.

[21] Hazel Katherine Hill, “Coeds Take Over Positions in Navy Lenoir Dining Hall: Women Replace Men in Essential Work,” The Daily Tar Heel, Saturday, April 17, 1943.

[22] Barbara Swift, “They Tell Me,” Daily Tar Heel, 5 August 1944.

[23] “Unknown Writer Insists Nazi’s Arrogant,” Daily Tar Heel, 8 August 1944.

[24] J. Derek Williams, “It Wasn’t Slavery Time Anymore: Foodworkers’ Strike at Chapel Hill, Spring 1969.” Master’s Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1979.

“Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike,” I Raised My Hand to Volunteer.

[25] J. Derek Williams, “It Wasn’t Slavery Time Anymore: Foodworkers’ Strike at Chapel Hill, Spring 1969.” Master’s Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1979.

“Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike,” I Raised My Hand to Volunteer.

[26] “The BSM’s 23 Demands: December 1968,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History.

[27] Williams, “It Wasn’t Slavery Time Anymore: Foodworkers’ Strike at Chapel Hill, Spring 1969.”

“Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike,” I Raised My Hand to Volunteer.

[28] “Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike.”

[29] “Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike.”

[30] “Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike.”

[31] “Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike.”

[32] “Part 3: The BSM and the Foodworkers’ Strike.”

[33] “Digital exhibit, audio documentary illuminate history of campus activism,” College of Arts and Sciences, University of North Carolina, November 1, 2017.

[34] Art Woodruff, “Lenoir Hall to have ‘first-class renovation’,” The Daily Tar Heel, Thursday, July 19, 1984.

[35] Woodruff, “Lenoir Hall to have ‘first-class renovation’,” The Daily Tar Heel, 1984.

[36] Woodruff, “Lenoir Hall to have ‘first-class renovation’,” The Daily Tar Heel, 1984.

[37] Liz Crampton, “Student reactions mixed on Lenoir renovations,” The Daily Tar Heel, September, 15, 2011.

[38] Jordan H. Walker, “Lenoir Dining Hall and Student Union to start renovations beginning next fall,” The Daily Tar Heel, December 6, 2010.

[39] Dave Hart, “UNC Arrest Protested,” The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), April 5, 2005.

[40] Sofia Edelman, “Die-in over police brutality staged at Lenior Dining Hall,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 29, 2016.

[41] Mark Lihn, “Lenoir serves black history-themed dinner,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 25, 2015.