By Caroline Collins

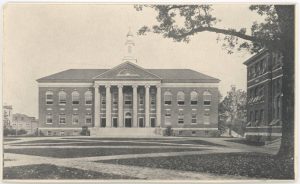

Manning Hall opened in 1923 and was subsequently named after John Manning who was a Professor of Law at UNC in the last two decades of the 19th century.[1] It sits between Murphy Hall and Carolina Hall, whose former namesake, William Saunders, became the focal point of a heated debate about the history of race on campus. Though it has not attracted similar attention, Manning has itself been the center of several racial issues at UNC. This humble building, which now houses the lesser known School of Information and Library Science on campus, had an active role in a movement that continues today. The desegregation of the Law School in 1951, as well as a African American Food Workers’ Strike in 1969, involved Manning extensively in the civil rights struggle on UNC’s campus. The relevance of Manning Hall’s’ history to the present is striking, and it’s role in the storied history of UNC’s campus is important in understanding the history of the civil rights movement at UNC.

Manning Hall’s Beginnings

Manning Hall, built in 1923, was one of several buildings to be constructed under an aggressive new building program at UNC designed to address the needs of a growing student population. Beginning in 1921,The program’s purpose was to “contemplate the erection during two years [1921-1922] of three class room buildings, five dormitories and several houses for members of the faculty, together with other structures.”[2] On January 26, 1921, the Board of Trustees discussed the establishment of this new building program, and they determined to ask the General Assembly to lend them money for the project.[3] During the 1921 regular session, the North Carolina Legislature granted $1,490,000 to the University as a building and permanent improvement fund through “an Act to issue bonds of the state for the permanent enlargement and improvement of the State’s educational and charitable institutions”.[4] In March 23rd of that year the Board established a Building Committee, named the Committee of Development of University Property, to oversee the Building Program and elected J. Bryan Grimes, John Sprunt Hill, George Stephens, James A. Gray, Haywood Parker, H.W. Chase, and Charles T. Woolen to compose it.[5]

The Committee soon hired T.C. Atwood as chief engineer of the Building Program, citing his graduation from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1897 and his “large and wide experience in private, municipal, and government work”[6]; he was given the task to “design and supervise construction of the buildings”. The consulting architects hired for the project were McKim, Mead, and White out of New York. Atwood, along with the Board of Trustees, hired T.C. Thompson and Brothers as the contractor for the project and the Aberthaw Construction Company was hired to make a preliminary survey of the buildings on the campus.[7]

According to plans by McKim, Mead, and White, the placement of Manning and the other academic buildings “on the West side of the Mall, South of the South Building” was intentional because the Board of Trustees believed that during the “future development of the physical plant of the University,” they needed, “to keep in mind and work toward the principle of centralizing as far as possible the academic teaching buildings around the South Building, as the administrative teaching center”.[8] The Committee also discussed the construction of a women’s building, but decided to postpone it until a later, unspecified date. While the other buildings involved in the Building Program were finished in 1922, Manning Hall remained incomplete. Building Committee minutes from the summer of 1923, however, revealed that “the work on the Manning Hall (the Law Building) was now progressing satisfactorily, after some delays” and it was “urged to push the work vigorously so as to get the building done in time for the [law] department to get in before the Fall term.”[9] Manning Hall was soon completed, and the School of Law moved in before the start of the Fall 1923 semester.

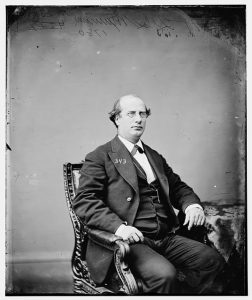

During a Board of Trustees’ meeting on June 13, 1922, the Building Committee recommended the new Law School be named for John Manning, citing his tenure as a Trustee at the University from 1875-1895. They also talked of his membership in the General Assembly and Conventions of 1861 and 1865 and his status as an adjutant C.S.A, meaning he assisted senior officers with administrative duties, as well as his time as a congressional representative from 1871-1873. Also discussed was his year as the Code Commissioner in 1881, his tenure as the Professor of Law at UNC from 1882-1899, and his authorship of the Commentaries of Blackstone,which was an extensive analysis on the Commentaries on the Laws of England written by William Blackstone that were utilized in the study of law at UNC. The Board of Trustees approved the naming of the Law Building after Manning during this same meeting.[10]

Beginning around 1949, Manning Hall underwent major renovations to expand its capacity to house a growing population of law students and faculty, as well as books. In 1948, the Dean of the Law School, Robert H. Wettach, wrote the Visiting Committee on the Board of Trustees that “Manning is and will continue to be completely inadequate for students, faculty, staff, and library.”[11] By August 1948 Dean Wettach forwarded his statement to Mr. H. Raymond Weeks, saying it “will give you a good picture of the problems we face in our present quarters.” The General Assembly session of 1949 appropriated funds for the addition, based upon the advice of the Advisory Budget Committee[12], and in faculty meeting minutes from May 6, 1949, the Law School faculty began discussing the changes they believed Manning needed.[13] The additions to Manning, which were completed around the fall of 1951, included a new wing, which “more than doubled the size of [the] building.”

Along with a new wing, Manning also received a new library reading room, three large study rooms and a large courtroom, as well as a student Lounge, new offices and classrooms, and special study rooms to accommodate blind students. A dedication ceremony, held in the new courtroom, and a reception were held on November 3, 1951, which were attended by prominent guests such as the President of the AALS (Association of American Law Schools) and Dean of the University of Virginia Law School, F.D.G. Ribble, North Carolina Speaker of the House, W. Frank Taylor, Chief Justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, W.A. Devin, and the President of the North Carolina State Bar, Louis J. Poisson.[14] During the ceremony, Lieutenant Governor H.P. Taylor stated, “I believe our people are even more anxious that not only the pages of the Constitution be preserved, but that its spirit be revived, restored, and promulgated” and that “the further strengthening of the facilities of this Law School we ardently hope will work toward this end.”[15]

Manning Hall and Desegregation

In the late 1940s and the early 1950s, Manning Hall became the center of the segregation debate at UNC. In the Plessy vs. Ferguson Supreme Court Case of 1896, the court ruled that “segregation was legal so long as equal facilities were provided for both races”.[16] Established in 1910, the North Carolina College for Negroes (currently known as North Carolina Central University) was considered as an “equal facility” for black students who desired to pursue graduate work in Law, Library Science, or other related fields. A law graduate program was first added to the North Carolina College for Negroes in 1939 in response to the Gaines v. Canada case, in which the Supreme Court allowed a black student to be admitted to the law school at the University of Missouri because the state had no “publically funded law school that would admit blacks.”[17]

However, black students applied to UNC despite the assumption that the North Carolina College for Negroes was the school they should attend. In light of these applications, the Board of Trustees resolved on June 2, 1948 that, “it is premature to consider any application of a Negro for admission to any University Graduate School until the individual qualifications and competitive standing of the applicant have been determined in the usual customary manner”; they also decided that applications for graduate programs at the University that were not offered at any other North Carolina schools “shall be processed without regard to color or race,” and would be, “accepted or rejected in accordance with the approved rules and standards of admission for the particular school.”[18]

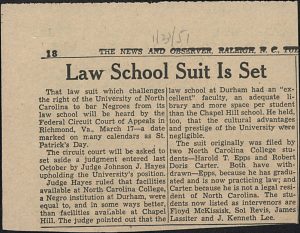

However, applicants to the School of Medicine and the School of Law felt they were unfairly denied admission. Several black applicants to the School of Medicine took UNC to court, and Floyd McKissick, along with other black students, sued the University and its Law School. They used the precedence of Sweatt v. Painter, which held that the University of Texas Law School was required to admit black students because other state facilities were inadequate, as the basis for their argument. The NAACP took on the student’s case, with Thurgood Marshall as lead prosecutor[19], while the North Carolina Attorney General Harry McMullan signed on as the defense attorney for the University. In the case of Epps v. Carmichael, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina sided with the University, saying that the state had provided adequate facilities that were equal to those offered by the University. The case was appealed and it went to trial in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, where the earlier District Court decision was overturned in McKissick v. Carmichael, which underwent a name change because Epps stepped down as the plaintiff. In their review the case, the Court of Appeals ruled that the law schools at the North Carolina College for Negroes and UNC were in fact unequal.[20]

The lawsuit against of the University and the School of Law met resistance by several members of the Board of Trustees, and in a meeting in March 1951, UNC President Gordon Gray of the University stated that he was “opposed to the admission of Negroes to our undergraduate schools or graduate and Professional schools in cases where the state has attempted to provide such facilities for Negroes.” Regarding to the recent overturning of the case by the Circuit Court of Appeals, he noted that he would,”…accept no less authority than the Supreme Court of the United States as to whether we have met the obligation we assumed.”[21] At a later meeting on April 4, 1951, the Board agreed that “any action taken at this time with reference to segregation at the University insofar as the Law School is concerned, would be premature,” and said that “further action be deferred until the final decision of the Supreme Court.” However, the University’s writ of certiorari was denied by the United States Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals filed an injunction against the University, stating that they couldn’t “deny entry to the plaintiffs.” Four black students were admitted to the UNC Law School in time for the summer school session of 1951.[22]

Even after the Law School was desegregated in 1951, its Dean at the time, Henry Brandis, took part in a Special Committee on Racial Discrimination created by the Association of American Law Schools (AALS), which evaluated discrimination at the Colleges and Universities across the country. In a report to the committee, titled Regarding the Situation as to Negro Students at the University of North Carolina Law School, Dean Brandis said that “I far as I was able to observe, the personal attitude of white students toward the Negro students was somewhat neutral. I saw no instances of personal discourtesy and has none reported to me.”[23] However, he reported that “our typical student does not approve of Negro participation in social affairs but is reluctant to abandon a traditional social function because of the presence of Negroes.”[24]

Later in the report, he talked about the University’s decision to issue the students separate toilet facilities, and how there had been no pictures taken in the law classes because “in future years a white student who happened to sitting next to a Negro student would find such a photograph used against him when running for some public office.”[25] Dean Brandis also discussed the University’s policy of not admitting non-resident African American students, which went against the AALS’s view on the matter. Evidently, the admission of African American students into the University’s Law School didn’t prevent it from continually discriminating against them, though discrimination abated over time.

Manning Hall and the Food Workers’ Strike

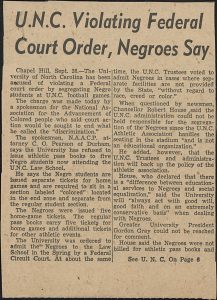

In 1969, Manning Hall again became the center of racial controversy on campus. The School of Law had moved to the new Van Hecke-Wettach Hall in 1968, leaving Manning vacant, pending renovations. During this same year, the Black Student Movement (BSM) started supporting the mainly African-American cafeteria workers who were being paid low wages. Ashley Davis, a member of the BSM, stated in a 1974 interview that “I think that the workers approached BSM simply because BSM had shown actual commitment, the leaders had shown commitment and interest prior to the strike and I think that people were looking for this. Like I say, we were committed, when we started out initially, we were committed. WE didn’t just talk.”[26]

According to Elizabeth Brooks, one of the leaders of the strike, the workers began comparing their paychecks and realized they were receiving less wages than previous paychecks, though they were working the same amount.[27] In December of 1968, the BSM issued a list of 23 demands with terms relating to the establishment of an African and Afro-American Studies and the increased admission of black students.[28] Early in 1969, some of the workers and BSM students met in Manning Hall to discuss the issues they were facing, but the workers were told by their manager to stop communicating with students.[29] On February 23, 1969, the Lenior Hall cafeteria workers, led by Mary Smith and Elizabeth Brooks, sat down at tables in the cafeteria and refused to work, beginning their month long strike characterized by its slogan, “It wasn’t slavery time anymore!”[30]

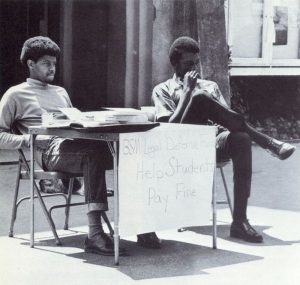

Due to its vacancy, Manning Hall became the strike’s home base, and the workers, in conjunction with students, set up a Soul Food cafeteria that was funded by donations for students boycotting Lenior. “We started a cafeteria with the workers,” said Ashley Davis, “so that the workers could make a living and by running the cafeteria, they made enough money that we were able to pay every worker $35 a week.”[31] Student demonstrators used Manning as a platform for speeches to encourage demonstrators to denounce the University administration.They believed the University to be negligent for ignoring the demands of the workers.[32] A student, writing for the Daily Tar Heel, stated that “From the beginning, the workers’ grievances have been much too important to arbitrarily ignore. The administration’s first response should have been to deal reasonably and sensibly with the workers, to examine their grievances and-where it is within the university’s power- to rectify them.”[33]

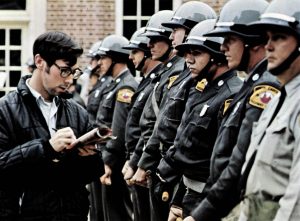

The peaceful strike turned violent, however, on March 4, 1969 when several students overturned tables in Lenior. Against the guidance of the President Friday and Chancellor Carlyle Sitterson, Governor Bob Scott called in state troopers and on March 13, 1969 to remove the strikers from the Manning Hall and closing the building, leading many people believed he was overreacting. Several students were arrested, but they were released on bail. In a meeting on March 14, 1969, the Board of Trustees unanimously voted to “endorse the recommendations of the of the Governor in his budget message to the General Assembly on February 12 requesting a 10% salary raise for non-academic employees.”[34] The strike officially ended on March 21, 2017 when Governor Scott conceded to the demands of the cafeteria workers. Because of the employees’ demands, the Government enacted statewide changes including the increase of the minimum wage to $1.80 for public University workers.

The strike, however, resumed in November of 1969 because of unfair treatment by the SAGA Food Services, who the University had contracted to manage the food services on campus in May of that year. SAGA began their time at the University by laying off 60 to 80 employees, and restricting the rest from speaking with students. On November 7, 1969, aro und 250 employees went on strike again, but against SAGA, though the issues being protested were of a similar nature because of unfulfilled promises from the previous strike. Throughout the duration of the strike, the University made clear the issue was with SAGA, and not them, but they worked to help displaced cafeteria employees jobs elsewhere on campus.The strike was ended on Sunday, December 9, 1969, the day before “Black Monday”, which was a planned convergence of black students from around the state on the University’s campus.[35] The 1969 strikes were not the last of the clashes between African-Americans and the University, or the cafeteria employees with the food management service on campus, but they brought together black activists and black and white protestors who worked together toward a common goal: the end of discrimination on the UNC campus.

und 250 employees went on strike again, but against SAGA, though the issues being protested were of a similar nature because of unfulfilled promises from the previous strike. Throughout the duration of the strike, the University made clear the issue was with SAGA, and not them, but they worked to help displaced cafeteria employees jobs elsewhere on campus.The strike was ended on Sunday, December 9, 1969, the day before “Black Monday”, which was a planned convergence of black students from around the state on the University’s campus.[35] The 1969 strikes were not the last of the clashes between African-Americans and the University, or the cafeteria employees with the food management service on campus, but they brought together black activists and black and white protestors who worked together toward a common goal: the end of discrimination on the UNC campus.

Manning Hall and SILS

In 1970, the renovations on Manning Hall were completed and it became home to the School of Library Science, which had existed on campus since the fall of 1931. The program was  started by Louis Round Wilson and the Carnegie Corporation extended it a grant of $100,000 to help it get on its feet. In 1987, after the School of Library Science had taken up residence in Manning Hall, the faculty of the program voted to reinvent the program, and rename the school to the School of Information and Library Science (SILS), when “it became apparent that the study of information use and management was of central importance to society.”[36] Though Manning Hall was involved in desegregation and the civil rights movement during, and right after, it was occupied by the School of Law, its years as home of SILS have been quieter.

started by Louis Round Wilson and the Carnegie Corporation extended it a grant of $100,000 to help it get on its feet. In 1987, after the School of Library Science had taken up residence in Manning Hall, the faculty of the program voted to reinvent the program, and rename the school to the School of Information and Library Science (SILS), when “it became apparent that the study of information use and management was of central importance to society.”[36] Though Manning Hall was involved in desegregation and the civil rights movement during, and right after, it was occupied by the School of Law, its years as home of SILS have been quieter.

Manning Hall’s Namesake

Manning Hall is named for John Manning Jr., who was the Professor of Law at UNC beginning in 1881 until his death in 1899. Manning was born in Edenton, NC on July 30, 1830 to John Manning Sr. and Tamar Haughton Leary. In 1803 his grandfather had left the family plantation, Manning Manor, located in Norfolk VA, and moved to Edenton where he became a merchant.[37] After a while Manning’s immediate family moved to Norfolk where he was admitted to the Norfolk Military Academy. In 1847, he joined the sophomore class at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, graduating from UNC in 1850 and becoming a licensed lawyer around 1853 under the tutelage of a family member named John H. Haughton.[38]

While before the Civil War he identified as a Whig, meaning he believed reunification with the Union would aid in the avoidance of war, he served in the Confederate military with the “Chatham Rifles” as a first lieutenant, and then an adjutant, during the first part of the war. Later, he was assigned the position of a receiver under the Sequestration Act of 1861, meaning he aided the Confederate Government in confiscating Union land and property held within the south. He was also a member of the Secession Convention, though he was reluctant to hastily vote on the Constitution of the Provisional Government and the Constitution of the Confederate States.[39]

After the war, Manning resumed practicing law. He was a congressional representative in 1870, though only for a short while because he was finishing the unexpired term of John T. Deweese. In 1975 he was appointed to the Constitutional Convention of 1875 and helped effect changes to the judicial department of North Carolina. He was a member of the state legislature beginning around 1880, during which time, as a staunch advocate of state funding for higher education, he introduced the first bill about giving an annual state appropriation for UNC. He also had a hand in “consolidating the public laws of the State”, which became law on March 2, 1883.[40] In 1881, Manning was unanimously awarded the position of the Professor of Law at UNC, which he held until his death in 1899. Manning was also a member of the UNC Board of Trustees from 1875-1895, coinciding with his tenure as the head of the Law Department.[41]

Footnotes

[1] “John Manning Jr., and Manning Hall,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed February 23, 2017, https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/names/manning-hall.

[2] Board of Trustees’ Minutes January 1917-January 18, 1924 (14 June 1921), “Boards of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932,” University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 23 February 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40001/

[3] Board of Trustees’ Minutes January 1917-January 18, 1924 (26 January 1921), “Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932,” University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collection Library, accessed 23 February 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40001/

<sup<[4]Board of Trustees’ Minutes January 1917-January 18, 1924 (14 June 1921).

[5]Board of Trustee’ Minutes January 1917-January 18, 1924 (23 March 1921), “Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932,” University Archives of the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 23 February 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40001/

[6]Board of Trustees’ Minutes January 1917-January 18, 1924 (14 June 1921).

[7]Ibid.

[8]Ibid.

[9]Building Committee 1923-1924, “Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932,” University Archives of the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 8 March 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40001/

[10]Board of Trustees’ Minutes January 1917-January 18, 1924 (13 June 1922), “Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932,” University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 23 February 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40001/

[11]Robert H. Wettach, “Statement Concerning the need of an Addition or Wing to Manning” From the University Archives of the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, School of Law of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1923-2005, accessed 24 March 2017.

[12]“New Law Building is Dedicated, Will Double Physical Facilities,” The Daily Tar Heel, 4 November 1951, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67831728 , pg. 6, (accessed 26 March 2017).

[13]“Minutes from Faculty Meeting Held May 6, 1949,” From the University Archives of the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, School of Law of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1923-2005, accessed 24 March 2017.

[14](Program from the Dedication) “Dedication of the Enlarged Manning Hall”, 3 November 1951. From the University Archives of the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, School of Law of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1923-2005, accessed 24 March 2017.

[15]“New Law Building is Dedicated, Will Double Physical Facilities,” pg. 6.

[16] “The First Black Law Students”, The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed 22 March 2017, https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/integration/the-first-black-law-students-i

[17]Charles Daye, “People: African American and Other Minority Students and Alumni,” UNC School of Law, accessed 3 March 2017, http://studentorgs.law.unc.edu/documents/blsa/african_american_and_minority_students.pdf

[18]Volume 3, May 26, 1944-January 21, 1950 (2 June 1948), “Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina (System) Records, 1932-1972,” University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 8 March 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40002/

[19]Floyd B. McKissick, Sr. oral history interview with Bruce Kalk, 31 May 1989, From the Southern Oral History Program, http://www.docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/L-0040/L-0040.html (accessed 24 March 2017)

[20]“People: African American and Other Minority Students and Alumni.”

[21]Volume 4, January 21, 1950-May 14, 1956 (22 March 1951), “Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina (System) Records, 1932-1972,” University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 3 March 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40002/

[22]“People: African American and Other Minority Students and Alumni.”

[23]“Report for the Association of American Law Schools Committee on Racial Discrimination Regarding the Situation as to Negro Students at the University of North Carolina Law School,” School of Law of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1923-2005, University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 22 March 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40046/#folder_178#1

[24]Ibid.

[25]Ibid.

[26]Ashley Davis oral history interview with Russell Rymer, 12 April 1974. From the Southern Oral History Program, http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/E-0062/E-0062.html (accessed 25 April 2017).

[27]Elizabeth Brooks oral history interview with Derek Williams, 13 August 1979. From the Southern Oral History Program, Labor: University of North Carolina Foodworkers’ Strikes, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sohp/id/10720/rec/6 (accessed 27 March 2017).

[28]“The Black Student Movement’s 23 Demands: December 1968,” Carolina Story: Virtual Museum of University History, accessed March 27, 2017, https://museum.unc.edu/items/show/1803.

[29]Elizabeth Brooks oral history interview with Derek Williams, 13 August 1979.

[30]“Women Behind the Lines.” University of North Carolina Library. Accessed 27 March 2017.

[31]Ashley Davis oral history interview with Russell Rymer, 12 April 1974.

[32]Wayne Hurder, “On Orders from Scott, Troopers Close Manning”, The Daily Tar Heel, March 14, 1969, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67743844 (accessed 23 February 2017).

[33]“Thursday’s Rally in Polk Place,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 16, 1969, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67743859/?terms=Manning%2BHall (accessed 25 April 2017).

[34]Volume 12, September 13, 1968- March 14, 1969 (14 March 1969), “Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina (System) Records, 1932-1972,” University Archives at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, accessed 3 March 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/40002/

[35]“I Raised My Hand to Volunteer.” Exhibit, from The University of North Carolina Library, http://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/protest/foodworker-essay (accessed 27 March 2017).

[36]“Our History,” UNC School of Information and Library Science, https://sils.unc.edu/about/history (accessed 26 March 2017).

[37]William J. Adams, The Life and Influence of John Manning, [North Carolina: Reprinted from the North Carolina Law Review, Volume 2, Number 4, December 1924], pg. 1.

[38]Ibid., pg. 2.

[39]Ibid., pg. 3.

[40]Ibid., pg. 4.

[41]“John Manning Papers, 1829-1899,” The Southern Historical Collection at the Louis Round Special Collections Library, accessed 23 February 2017, http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/01970