By Anna Blackwell

Introduction

In recent years, the history of the campus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has come into the spotlight. From buildings named after white male supremacists to unnoticed landmarks built by black slaves, UNC’s campus possesses issues of race and gender embedded into its geography. Peabody Hall, home to UNC’s School of Education, is not exempt from a history surrounding race and gender: its namesake, George Peabody, had major influence upon discussions of race in the United States during the 19th century, and the building has a history associated with second-wave feminism. These factors make Peabody Hall more than a simple building, but a powerful site full of history that deserves to be studied.

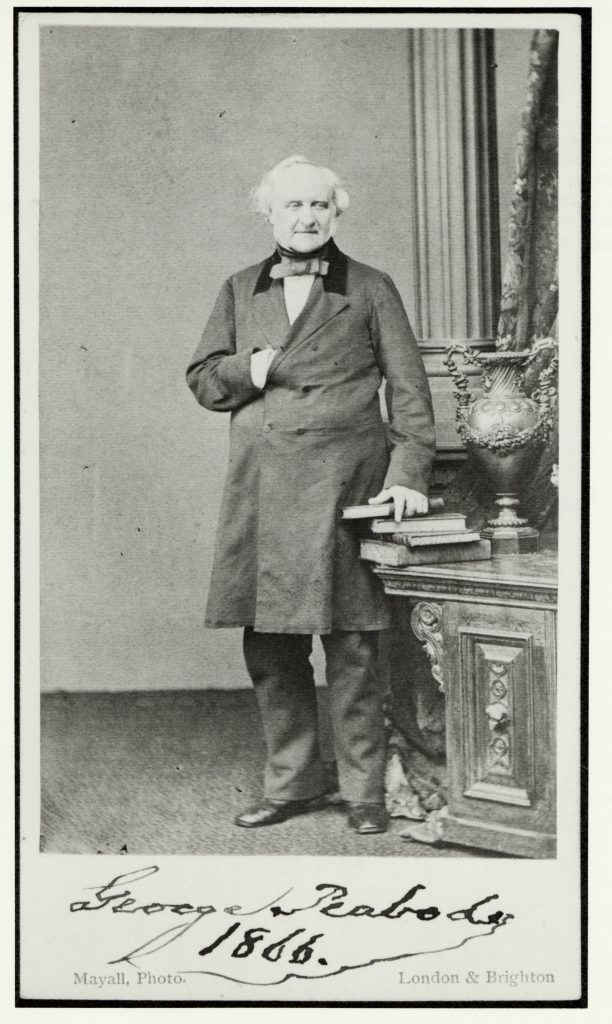

George Peabody

George Peabody was born on February 18, 1795 to Thomas Peabody and Judith Dodge. The Peabody family had migrated to Massachusetts from England in the 17th century, and settled in Danvers, Massachusetts. George was one of seven children, and despite the work ethic of the family, the Peabodys suffered from poverty, particularly after Thomas’s death in 1811. Peabody was unable to receive a proper education growing up, and the education he did obtain at the Danvers school was primitive and short lived as school terms only lasted a few months. The limited education Peabody received in his youth greatly influenced his later educational philanthropy after he became wealthy.1

Lacking higher, formal education, Peabody began an apprenticeship under his uncle, a merchant, as a teenager. The two traveled south to Georgetown, Maryland, and opened a dry goods store, where George gained business experience. He later began his own company with another merchant named Elisha Riggs, which they expanded to Baltimore. The state of Maryland became especially significant for Peabody for the rest of his life and a major site for his charity work.2

Riggs, Peabody, and Company was so successful that the two men decided to move away from merchandising and become financiers of trade. Aware that London was the dominant international financial center, Peabody looked to Europe to expand his business endeavors. Eventually, the company spread across the Atlantic, affording Peabody international business experience. Peabody enjoyed traveling to England on his business ventures, and was so prosperous there that he settled in England permanently in 1837, where he became one of the most wealthy investment bankers in the country.3

After settling in England, Peabody spent time traveling around the country. From his travels, he became aware of the poor living conditions that many people lived in. With more wealth than he had ever had in his life, he began to realize the importance of charity. In 1864, he gave £500,000 to open the first of his “Peabody Housing Estates” in London, which provided cheap housing in close proximity to railroads and a grocery store with affordable prices. His philanthropic work garnered Peabody fame in England and recognition from Queen Victoria.4

Peabody Education Fund for the South and Race

Despite living abroad for the majority of his life, Peabody remained connected to his home country and wanted to contribute back to it. He made a trip to America in 1866 intending to create a fund to aid people living in poverty in New York City, similar to his housing charity in London. However, after traveling through the South and seeing how destitute it had become after the Civil War, he decided to redirect his donations to that region.5

Peabody felt that the best way to aid the southern states was through educating their youth, who were mostly illiterate. With the help of his advisor Robert Charles Winthrop he created the Southern Education Fund with an initial donation of one million dollars. Winthrop chose suitable trustees for the fund, and appointed Barnas Sears as director of the administration. Sears had formerly been secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education and president of Brown University, making him an ideal candidate. Sears monitored the Fund to ensure that unstable southern schools received aid to become self-supporting, new schools be built in communities that had none, and donations be given to normal schools (teacher training schools) to produce quality teachers.6

President Andrew Johnson welcomed Peabody’s gift to the South, hoping that it would be a factor in reuniting the country after the Civil War.7 Although Peabody did not support southern secession and was opposed to slavery, he still faced difficulties choosing a side. He had been living in England for decades, making him somewhat removed from the conflict. His strong ties to the border state of Maryland complicated matters, as many of his friends supported the Confederacy.8 Nevertheless, Peabody was adamant that the money from the Peabody Education Fund would go to not only white students, but also to recently freed African Americans. Thus, he directed that the benefits “be distributed among the entire population, without other distinction than their needs and the opportunities of usefulness to them.”9

Unfortunately, Peabody did not live to see the effects of his philanthropy. In failing health, he gave the Fund another one million dollars in 1869, and shortly thereafter a final 1.5 million dollars.10 On November 4, 1869, George Peabody died in London at seventy-four years old. The trustees of the Education Fund, particularly Sears, decided how the Fund’s money would be spent.

Despite Peabody’s wishes for racial equality, aid from the Fund was not equally distributed. Reasoning that white people were in much greater need for monetary aid because black students were receiving better education resources from the Freedmen’s Bureau and northern missionary societies, of the 1.2 million dollars distributed to southern schools, Sears gave only about 6.5% ($75,750) to black schools.11

The Peabody Education Fund excluded giving aid to African American communities due to the conditions the Fund required. In order to receive aid:

- communities were required to raise an amount of money three or four times the amount donated by the fund, to encourage the acceptance of school taxes

- the schools had to be under the public to prevent private control

These conditions caused the Fund to give more money to white rather than black schools, as black communities had difficulty raising large sums of money to match Fund donations. Black schools were also often held in church buildings, which were under control of private church trustees, not the public.12

The Peabody Education Fund Board of Trustees. Courtesy of the Peabody Institute, Johns Hopkins University.

Beginning in 1870, the Fund began donating money to white and black schools in a similar manner. However, the amount given to black schools was much less. An average white school at the time received $300, whereas black schools received $200 on the grounds that “it cost less to maintain school for colored children than for the white.”13

Republicans criticized the Peabody Education Fund due to it promoting racial segregation in schools. When the radical Louisiana constitution drafted during Reconstruction called for mixed-race schools, many whites pulled their children out of the public school system and established white-only private schools. Sears felt that this negatively affected the white students, who lacked support from the state. In response, Sears made the decision to donate Fund money to these private white schools in Louisiana, an uncharacteristic action for the Fund, which usually only supported public schools.

Republicans condemned the Fund for this, and Sears responded that if the situation was reversed, and black students refused to attend school with whites and left the public school system, then the Fund would have aided black students. However, there were instances that proved this claim false. In 1874, Kentucky implemented a system that required education for African Americans to be funded with taxes from black citizens only. This obviously led to inadequate funds, as blacks were systematically prevented from having occupations with high incomes. In this case, the Fund made no contributions.14

Sears was also a controversial figure because he lobbied to Congress to prevent school integration. In 1874, Sears traveled to Washington, D.C. to argue against a proposed civil rights bill. Sears was not opposed to African American civil rights in the United States as a whole, but did feel that integrating the schools would destroy the emerging state school systems that the Fund was trying to establish. Sears feared that if the states forced integration, the southern region would revert to a traditional private school system, causing blacks and poor whites to suffer.15 This lobbying by Sears, while probably well-intentioned, did not accurately aid black and white education in the South equally as George Peabody had intended, making Peabody’s name a source of disapproval in later centuries.

Post Civil War Education in North Carolina

Following the Civil War, North Carolina was readmitted into the Union, and as part of its reentry, the state was required to draft a new state constitution. This 1868 Constitution required the University of North Carolina to educate teachers for the state’s schools. Article IX, Section 17 made public education compulsory for all able-bodied children:

“The General Assembly is hereby empowered to enact that every child of sufficient mental and physical ability, shall attend Public Schools during the period between the ages of six and eighteen years, for a term of not less than sixteen months, unless educated by other means.”16

Article IX, Section 16 recognized the need for qualified teachers and directed the University to educate teachers for North Carolina’s schools:

“As soon as practicable after the adoption of this Constitution, the General Assembly shall establish and maintain in connection with the University, a Department of Agriculture, of Mechanics, of Mining, and of Normal Instruction” (education and teaching).17

After North Carolina ratified the new state constitution, Governor Vance called a meeting of the State Board of Education to determine how to begin an education program at the University. As general agent of the Peabody Fund, Sears recommended a free summer school program that would train young white men to be effective teachers. He offered $500 out of the Peabody Education Fund to pay the expenses of poor teachers, and the State Board accepted the idea. The University hosted the first summer school in the United States for a group of teachers in 1877. The state legislature gave the school $2,000 per year to support this summer program, in addition to Sears’s financial aid from the Peabody Fund.18

The University provided the summer school program for teachers every year until 1884. It was a great success, and inspired other summer normal schools in the South. In 1885, the University established the Department of Pedagogy, making it one of the oldest professional schools on campus. After almost three decades, with a rapidly expanding campus and growing education department, the University changed the Department of Pedagogy to the School of Education. At this point, the University’s education school needed a much larger space to fulfill its duties to the state.19

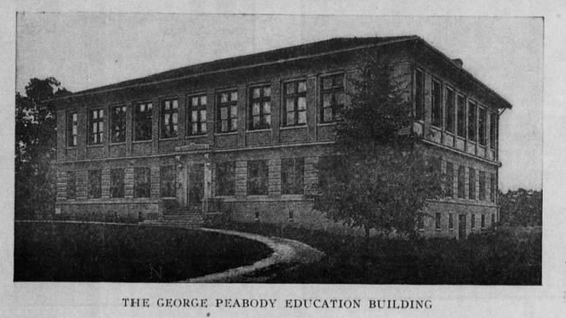

Construction of Peabody Hall

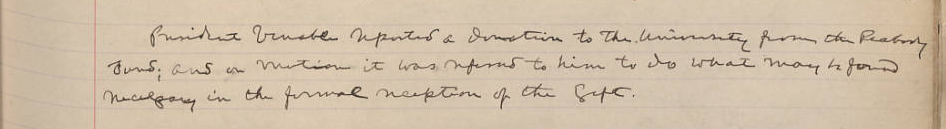

In the early 20th century, UNC began a rapid expansion of new buildings and facilities. University President Francis P. Venable headed this expansion, and tirelessly sought out funding for campus development.20 After reaching out to the Peabody Education Fund, Venable announced on May 29, 1911 that he had acquired a $40,000 donation for the construction of a new building for the School of Education.[21] The only condition from the Fund was that the University devote $10,000 annually to support education in the South.22

UNC Board of Trustees minutes, May 29, 1911. Courtesy of the University Archives at Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

Construction for the building began in 1912 with a design from the architect group Milburn and Heister of Washington, D.C. The edifice was built on 4.3 acres of land purchased from Mrs. Julia C. Graves for $10,000. The original Peabody Hall was two stories of white brick, containing 42 rooms (19,600 square feet).23 For the dedication ceremony on May 2, 1913, high school teachers from across North Carolina met for a conference to discuss what the School of Education at UNC, in it’s new structure, would do to aid the state.24

1930 Renovation

In the late 1920s, the University announced plans to renovate the interior of Peabody Hall. The 1927 state legislature had made plans to add a new wing to the building, but due to a lack of funds, plans were instead changed to renovating the interior of the building for $50,000.25

Renovation plans included enlarging the Peabody basement, altering the layout of the first and second floors, adding classrooms, and improving the arrangement of offices for administrators and professors in the School of Education.26 A stock room, filing room, shipping room, women’s restroom, and laboratory for the bureau of educational records were added to the basement. Offices for the educational psychology, history of education, and educational research departments were added to the second floor. The renovation also included new hardwood floors and plaster to replace the wood ceilings. The exterior of the building remained unchanged.27

In the winter of 1930, the renovations began under the Atwood Nash organization. T.C. Thompson and Brothers, who built a number of the University’s buildings in the early 20th century, completed the work for the renovation.28 During the construction, the education department moved operations to the old library building on campus.29

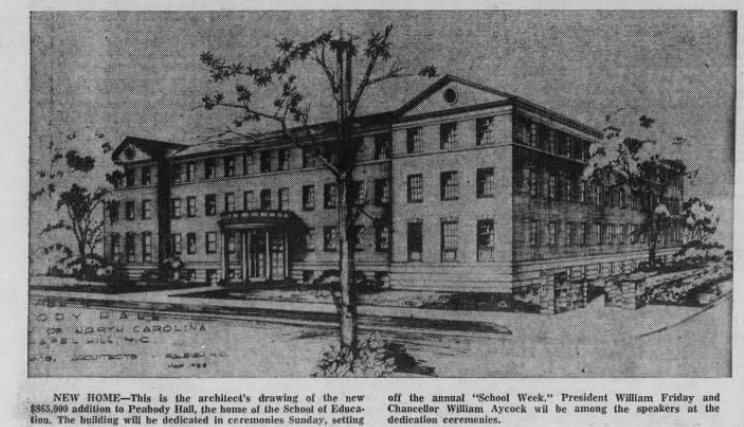

1960 Addition

In the 1960s, the planned additional wing to Peabody Hall from the 1920s became a reality. In 1956, University officials asked the state for 16 million dollars to expand the campus, including new academic buildings and dormitories. For the Peabody Hall addition, UNC requested $776,779 for the new wing and $90,000 for equipment.30 The 1960 addition is the most recent significant alteration to the Peabody building.

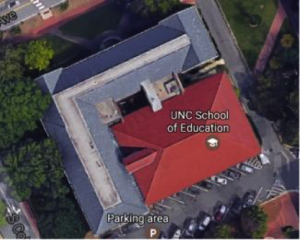

The state approved the money request, and construction for the new addition began in February of 1959.31 The addition has quite an interesting design, as it is an L-shaped wing that wraps around the front and west side of the original Peabody Hall built in 1912. The exterior of the new addition was designed to complement the architecture of the Carolina Inn, the closest building to the west of Peabody.32 This wing is four stories tall, and more than triples the space of the original building.33

The 1960 addition plans included many modern features for the School of Education, such as a demonstration classroom for elementary classes, a science demonstration classroom, a new library, a reading clinic, enlarged testing services, and an audio-visual center. One of the most exciting changes was that the entirety of Peabody Hall became air-conditioned, making it the first building on UNC’s campus to be fully air-conditioned. Overall, the new wing cost the state $865,000.34

Aerial image of the L-shaped addition surrounding the original Peabody building. Courtesy of Google Maps.

The dedication ceremony for the new addition to Peabody Hall was held on June 19, 1960 at 8 P.M. It was dedicated by University President William C. Friday, with participation from Chancellor William B. Aycock and Arnold Perry, Dean of the School of Education. Another notable guest was Charles F. Carroll, Superintendent of Public Instruction in North Carolina. This dedication ceremony kicked off “School Week,” a four-day conference on education held annually at the School of Education at UNC, where top educators from across the state would meet to discuss tactics to improve education in North Carolina.35

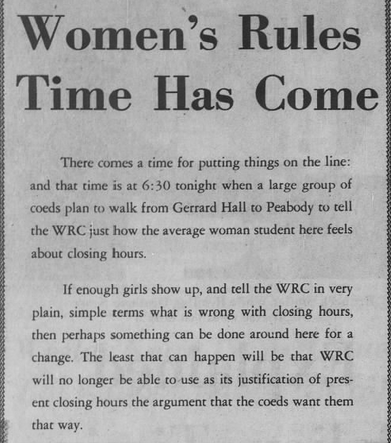

Female Associations and the Women’s Rights Movement

Peabody Hall has always been an academic building on the University’s campus and has always been home to the School of Education. However, significant extracurricular activities outside of teaching occurred in this building. A prominent way students utilized Peabody Hall was through the Women’s Rights Movement of the 1960s. Female student groups and organizations on campus (such as the Women’s House Council and various sororities) often used Peabody for their meetings.36

Peabody Hall was also used to host meetings regarding domestic topics. In November of 1966, UNC held a “Senior Coed” meeting in Peabody Hall to help female students make decisions regarding their futures, informing them of job opportunities for women.37 That same month, the UNC Student Wives’ Club held a meeting in Peabody to discuss marriage and family life.38

Peabody Hall also has significant ties to the Women’s Rights Movement. On January 9, 1968, a number of female students at UNC, allied with the Women’s Residence Council and Women’s Honor Council, participated in a “Coed Walk” from Gerrard Hall to Peabody Hall to protest against “closing hours.” These University-mandated hours required female students to be in their dormitories after a certain hour, whereas males were free to travel through campus whenever they pleased. Feminists felt this rule gave them a second-class status on UNC’s campus, and used Peabody Hall as the location to protest.39

One has to wonder why these feminist women’s activities occurred at Peabody Hall. Out of all the buildings on UNC’s campus during the 1960s, nearly all women’s group activities occurred there. Perhaps this is due to Peabody Hall being the location of the School of Education and the historic trend of females working as teachers, making it an obvious and comfortable place for women to meet. However, it is ironic that women met in this building as they had originally been excluded from it, because it took many years before women were accepted into UNC and allowed into the School of Education.

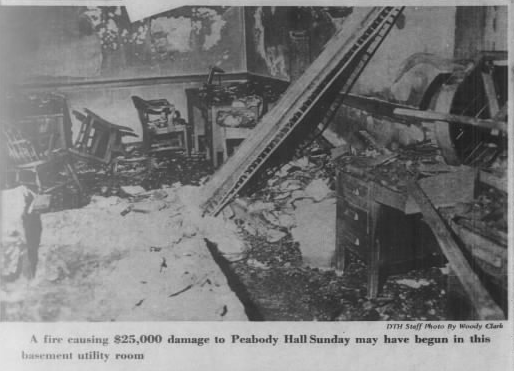

Arsonist Fire

In the late 1960s, Peabody Hall was the target of a dangerous arson attack. On October 19, 1969, someone set fire to four University buildings: Bingham, Murphey, Gardner, and Peabody Halls. While the damage to Bingham, Murphey, and Gardner was small and consisted of a few burnt desks and trashcans, the destruction to Peabody was the worst, causing $25,000 worth of damage. Chapel Hill Police Chief W. D. Blake claimed that the pyromaniac had acted randomly in buildings that happened to be unlocked at the time, rather than targeting specific buildings.40

Conclusion

The buildings on the University of North Carolina’s campus are more than simple structures. These buildings often have intense histories, especially regarding the personal and public lives of the people they are named after. In comparison to some of the other buildings on campus, such as Daniels Student Stores and Aycock Dormitory, George Peabody was a much more worldly, liberal man with good intentions regarding his aid for both blacks and whites in the South. However, due to the actions of the men who ran his fund after his death, Peabody’s name does possess racist associations.

Despite this darker history uncovered surrounding Peabody Hall, there have also been beneficial events that have occurred in this building. For many of UNC’s former female students, the Peabody building served as a place for women to convene and support one another. Peabody Hall, for whatever reason, became a haven for participants in the feminist movement of the 1960s, giving this building a positive history.

As a dynamic structure, Peabody Hall’s story has not ended, but is constantly making history and will certainly continue to do so. It is the responsibility of the students and faculty at UNC to learn of the namesakes of buildings and decide whether these people are worthy of having a structure on this campus named after them. By using the abundant research materials available at the University, students can learn more about the history of this campus, including Peabody Hall. Using The Daily Tar Heel articles, students can not only discover the interesting ways students have utilized the Peabody building, but can also experience what the atmosphere of UNC’s campus was like decades ago.

For more information on George Peabody, I point students to explore Robert Van Riper’s book A Life Divided and Franklin Parker’s book George Peabody: A Biography, which give a comprehensive understanding of the philanthropist’s life, both personal and professional. The Peabody Fund by Edgar W. Knight and A Brief Sketch of George Peabody and Speech of Hon. J.L.M. Curry, General Agent of the Peabody Education Fund, Delivered Before the North Carolina Legislature by J. L. M. Curry provide detailed information on the Peabody Education Fund and it’s operations in the southern states. From sources such as these, students can educate themselves and form an opinion on the worthiness of the namesake of Peabody Hall.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Franklin Parker, George Peabody: A Biography (Rev. ed. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1995), 4-10.

2 Parker, 11-15.

3 Robert Van Riper, A Life Divided: George Peabody, Pivotal Figure in Anglo-American Finance, Philanthropy and Diplomacy (Philadelphia: Xlibris Corp., 2000), 22.

4 Van Riper, 155.

5 Van Riper, 160.

6 Parker, 160.

7 Parker, 164.

8 Van Riper, 147.

9 Earle H. West, “The Peabody Education Fund and Negro Education, 1867-1880.” History of Education Quarterly 6, no. 2 (1966), 4.

10 Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University (Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1965), 216.

11 West, 4.

12 West, 9.

13 West, 11.

14 West, 15.

15 West, 16.

16 UNC School of Education, “Historical Timeline – Celebrating 125 Years.” http://soe.unc.edu/125years/timeline.php.

17 Ibid.

18 Kemp P. Battle, History of the University of North Carolina (University of North Carolina, 1907), 142.

19 UNC School of Education, “Historical Timeline – Celebrating 125 Years.” http://soe.unc.edu/125years/timeline.php.

20 “Fundraising in the Early Twentieth Century.” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, 2006. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/early-benefactors/francis-preston-venable–1856-

21 Oversize Volume 11: May 1904-September 1916 (Reel 4): Scan 311 in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

22 UNC School of Education, “Historical Timeline – Celebrating 125 Years.” http://soe.unc.edu/125years/timeline.php.

23 Henderson, 217.

24 “Completer Head to Schools.” The Daily Tar Heel, April 26, 1913.

25 “Extensive Improvements Will Be Made on Peabody Building; To Remodel Interior of Hall.” The Daily Tar Heel, December 14, 1929.

26 “Extensive Improvements Will Be Made on Peabody Building; To Remodel Interior of Hall.” The Daily Tar Heel, December 14, 1929.

27 “Renovation of Education Hall Now Underway.” The Daily Tar Heel, January 30, 1930.

28 Henderson, 217.

29 “Extensive Improvements Will Be Made on Peabody Building; To Remodel Interior of Hall.” The Daily Tar Heel, December 14, 1929.

30 “UNC Officials Ask $16 Million for Permanent Improvements of School.” The Daily Tar Heel, July 20, 1956.

31 “Next Decade Will Cover UNC Expansion.” The Daily Tar Heel, January 31, 1959.

32 Wall text, Peabody Hall Addition, Peabody Hall: School of Education, Chapel Hill, N.C.

33 Henderson, 216.

34 “33-Year Old Faculty Request Answered In Peabody Hall.” The Daily Tar Heel, June 23, 1960.

35 “Addition Cost $865,000.” The Daily Tar Heel, June 16, 1960.

36 “Campus Calendar.” The Daily Tar Heel, October 18, 1966.

37 Steve Bennett, “Senior Coeds Will Have Job Meeting.” The Daily Tar Heel, October 27, 1966.

38 “Campus Calendar.” The Daily Tar Heel, November 29, 1966.

39 Karen Freeman, “Coed Walk Could Change Rules.” The Daily Tar Heel, January 9, 1968.

40Al Thomas, “Arsonist Hunt Continues; Campus Security Tightened.” The Daily Tar Heel, October 21, 1969.