From Chapel to Music Hall

Throughout its 220 years of existence, Person Hall has been the poor sister on the UNC campus. Architecturally, it is small and simple unlike its contemporaries Old East and South Building. Original construction was delayed due to lack of funds; once it was built, it was uncomfortable; and over the years it has been repurposed repeatedly. The most recent campus survey of historical buildings lists its condition as poor, with no plans for fixing the problems. And yet there’s a spirit associated with the space that has prompted faculty to advocate against its demolition and inspired a wealthy benefactor to invest in its beautification. This is the story of Person Hall and the American patriot for whom it is named. A thin story, due to a dearth of archival material, but a story nevertheless.

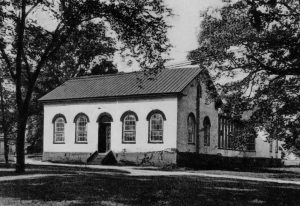

“Person Hall, circa 1892” in Kemp Plummer Battle Photo Collection, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

Chapel Construction (1795-1798)

No records exist to document the Trustees decision to build the chapel. Even William Powell in his extensive history of the University skips over any mention of the chapel’s origin other than to say it was delayed in opening.[1]

Philemon Hodges, a free African-American from Hillsborough, built the chapel under the supervision of Samuel Hopkins.[2],[3] The foundation had been laid by 1796 but “when it was barely above the ground the treasury ran low; when the strong box was tapped it gave a hollow sound.”[4]

Thomas Person, a Trustee and a fierce advocate for public education, stepped forward to donate the $1,050 funds needed to complete the construction.[5] In thanks for his generosity, the Trustees passed the following resolution:

“Resolved, that the Board have a proper sense of the liberality of General Person in the important and benevolent condition by him made as above mentioned; and that they offer him their thanks for the same; assuring him likewise that proper mention shall be made of such his bounty in the Records of the University.”[6]

Even with Person’s silver, the construction proceeded slowly, straining the relationship between the Trustees and Mr. Hodges. William R. Davie [Trustee] in a letter to John Haywood [Trustee] wrote “I mentioned to you when at Raleigh the insufficiency of the work which had been done by Hodge at the chapel, and the necessity of his being informed that we would not receive it….I entreat you to take the necessary measures with regard to Hodge before he proceeds further with the building that he may have no reason to complain of us, I am fully convinced that man has no intention of compleating his contract without a Law-suit; we ought therefore to be circumspect, and continually press him without relaxation to do his duty.”[7]

Dissatisfaction with the construction did result in a law suit, as Davie predicted, but it was brought by the Trustees against Hodges rather than the other way around. “A lawsuit was eventually enjoined against builder Philemon Hodges, and thus it is hard to determine when the building was actually finished. Though the contract called for completion by July 1797, it was obviously not completed at that time, and the arbiters of the lawsuit sent to judge the quality of the building did not make a report until December 4, 1798.”[8]

The arbiters’ report is not the archives but Powell, Snider, Shumann, and Coates all speculate that the construction was close enough to completion for the first commencement ceremonies to be held at the chapel in 1798.[9],[10],[11],[12]

The Chapel (1798 – 1837)

Architecturally, the original (east section) Person Hall measured thirty-six by fifty-four feet. The survey for the National Register of Historic Places describes it as “federal style of Flemish-bond brick construction with a stone foundation and projecting brick water table. It has a standing-seam metal roof with boxed eaves, partial cornice returns, and arched fourteen-over-eight woodsash windows in arched brick openings with stone windowsills. The eight-panel door, centered on the façade, has an arched ten-light transom and fluted pilasters and is accessed by an uncovered brick stair.”[13]

Students and faculty came to the old chapel twice a day for sunrise and sunset prayer services. The community joined them for church on Sundays. The chapel was also the community center serving as the campus site “…for all assemblies, sacred and profane, at one hour decorous divine worship, at another a boisterous mass meeting of students, at another academic exercise of speaking, at others, the various exercises of Commencements.”[14]

1832 Speech by alumni William Gaston declaring that slavery obstructed Southern progress and urging preservation of the Union.

The only first-hand account of conditions within the old chapel come from William Hooper looking back on his student days, “It was in your old chapel, that the Dialectics of my day used to carry on their comfortless sessions, on a naked dirty floor & seated upon hard coarse benches — & doomed, in the winter time, there to shiver out the long cold nights, without a fire.”[15]

Despite the spartan conditions, meaningful debate was carried out in the chapel over its 40 years as the central meeting space of the Philanthropic and Dialectics societies. Two speeches stand out. In 1827, Archibald D. Murphey summarized the “state of American literature” in the first address jointly sponsored by the Dialectic and Philosophical Societies.[16]

In 1832 at the same Dialectic and Philosophic Society event, William Gaston spoke out against slavery and entreated his audience to preserve the Union. “I entreat and adjure you then, by all that is near and dear to you on earth–by all the obligations of Patriotism–by the memory of your fathers, who fell in the great and glorious struggle–for the sake of your sons whom you would not have to blush for your degeneracy–by all your proud recollections of the past, and all your fond anticipations of the future renown of our nation–preserve that Country, uphold that Constitution. Resolve, that they shall not be lost while in your keeping, and may God Almighty strengthen you to fulfil that vow!”[17]

The General (1733-1800)

Thomas Person, son of William and Ann Person, lived his entire life in Granville County, North Carolina. His wealth accumulated from land purchases while working as a surveyor under Lord Granville prior to the American Revolution. Shortly before his death, tax records show that he owned land in 10 separate North Carolina counties and three Tennessee counties. He married Jeanna Thomas in 1765 and, although they had no children of their own, they adopted Person’s nephew, William Person Little, as their heir.[18],[19] Not much more than this is known about his private life. As Wheeler noted, “It is a matter of regret that more of his life, services, character, and death, have not been obtained. It is to be hoped that some future pen may record his services and virtues.”[20]

Although more is known about his political career than his private life, what is known is mostly summary or the position he filled and the dates. His political career began in Granville County where he served as Justice of the Peace and Sheriff. In 1764, he was elected to represent Granville in the North Carolina General Assembly. He went on to serve on all five of the Provincial Congresses between 1774 and 1776.[21]

During the War of Regulation (1765-1771), Person joined with the farmers of the Piedmont to oppose governmental abuses under Governor Tryon. The Regulators didn’t object to paying taxes, but they expected those taxes and fees to be set fairly and the collection to be regulated. Person’s role was to review citizen complaints and subsequently seek redress from Tryon’s administration. When those attempt at reason failed, battle ensued at the Battle of Alamance (1771).[22]

Person is identified as one of the leaders of the Regulators, but his contribution was to the administrative side of the rebellion. Although he was not present at the Battle of Alamance, Tryon’s agents arrested him anyway and held him in Hillsborough following the battle. Three weeks later he was released without trial or further penalty.[23],[24]

As a Brigadier General during the first year of the Revolutionary War, Person again offered his business expertise by recruiting troops and collecting supplies. He resigned the military post in 1777 to assume a seat on the North Carolina Council of State.[25]

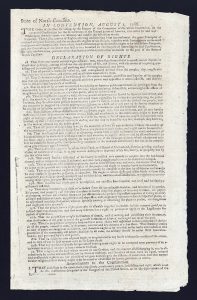

Following the war, Person helped draft the North Carolina Constitution. He and the other anti-federalists unsuccessfully argued for limited central government, but won the battle to include a Declaration of Rights in the state Constitution.[26] Those rights were later adopted, in large part, as the federal Bill of Rights.

As Russell Phillips claimed, “Those persons acquainted with the political battles of this period can, as they pass and look upon sturdy Person Hall, reflect that the man for whom it is named was in some measure responsible for the fact that we enjoy today the basic rights of speech and press, assembly, petition and religion as contained in the amendments to the United States Constitution.”[27]

When the 1776 Constitution was amended in 1789 to include a charter for the University of North Carolina, Person was appointed as one of the original Trustees.[28],[29] The record of his participation as a Trustee is limited to his donation of the funds to complete the chapel.

In her history of Alamance County and the Regulator movement, Sallie Walker Stockard described Person as “one of the most remarkable men of his time…North Carolina holds in her bosom the bones of no truer patriot and statesman.”[30]

In a similarly laudatory vein, Battle claimed that he was “among the band of forty of the greatest men the State had in 1789–the first Board of Trustees of the University, among whom were six Governors, eight Judges, of whom two were Judges of the Supreme Court of the United States, fifteen members of Congress, of whom three were Senators…”[31]

Weeks sums up General Person’s lasting contribution to the state, “…Thomas Person’s most important and valuable service to North Carolina was not as an Anti-Federalist member of the conventions of 1788 and 1789 nor as a military man nor as a philanthropist but as a member of the General Assembly. There he was always active, generally a radical, always an argus-eyed guardian of the rights of the people, an advocate, ardent, insistent and constant of the interests of the masses, and consequently hated and always feared by the representatives of the aristocratic, conservative interests.”[32]

After the Chapel (1837- 1977)

With the opening of Gerrard Hall in 1837, rumors circulated that Person Hall was to be demolished. Faculty responded with a petition to the Trustees to preserve the old chapel. “We understand that it has been proposed to demolish the Old Chapel (Person Hall) so soon as the new building shall be competed. It has doubtless been supposed it would then be of no use whatever. But for reasons which we could mention at length if it were necessary the place where we now assemble for morning and evening prayers is much more convenient for that purpose than the new building will be and we should give it up with extreme reluctance. We believe it will hardly be destroyed for the sake of the materials. It is not a splendid but it is a very neat edifice and we hope that unless there are strong reasons for pulling it down it may be suffered to remain. The New Chapel Hill be in a better state of neatness and preservation for public worship on Sunday and for Commencement.”[33]

The historical record on the Person Hall becomes even less detailed once it was no longer the university chapel. In 1842, it was divided into four classrooms with “thick walls and large chimneys.”[34],[35] Although the University Trustees continued to meet there when they were on campus, the building was no longer a center of campus activity.

In 1877, the dividing walls were removed and shortly thereafter, fire destroyed much of the interior. Julian Carr donated the $1,000 needed to make repairs after the fire.[36]

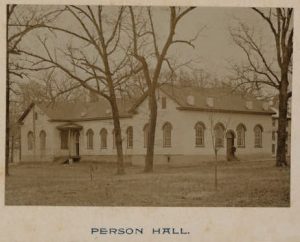

A connecting wing was added to the original building in 1886 to house the first dedicated chemistry lab on campus. A second wing was added in 1892 to accommodate the growing Chemistry Department. These new additions match the style and scale of the original construction.[37]

By 1936, the Chemistry Department had moved out and the Medical Department and the Pharmacy Department had also come and gone. Using New Deal funds, students renovated the interior of the old chapel to serve as an art gallery.[38] As part of the remodeling for the art gallery, Katherine Pendleton Arrington, one of the founders of the Mint Museum in Charlotte, donated two gargoyles and a stone statue of a thirteenth-century Archbishop that had been removed from London’s Westminster clock tower.[39],[40] Those decorative artifacts were installed on the south side of the 1892 wing of the building where they continue to reside today.

During the university’s bicentennial in 1995 a Memorial to the Founding Trustees was added to the north side of the 1892 addition. The memorial is a marble obelisk with a bronze profile of William Richardson Davie and a bronze plaque, inscribed with the names of the original members of the Board of Trustees.[41]

To the Memory of

the Founding Trustees of

The University of North Carolina

1789-1795

Music Hall (1926 – 1930, 1977 to present)

From 1926 to 1930 the old chapel housed the music department. In 1977, after interim service as storage space, a shop for Playmakers, and archaeology labs, the music department once again took up residence.

Today, Person Hall is composed of two recital rooms connected by a corridor (1892 addition) of offices. The original wing (east) retains its Colonial-styled wood trim and molding. The windows in the 1892 addition have been bricked in, an alteration that may have occurred during the 1936 remodel.[42]

On any given day as you walk through McCorkle Place, you may hear jazz riffs wafting from the practice rooms or the melodies that once accompanied early worship services in the old chapel.

In 1978, this author attended her first jazz concert in Person Hall as part of the History of Jazz course taught by Jim Ketch. The building holds a very sweet spot in her heart.

[1] William S. Powell, The First State University: Pictorial History of the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill; University of North Carolina Press, 1972), 23.

[2] Paul Hardin Kapp (Campus Historic Preservation Manager), Person Hall Campus Preservation Survey, (Chapel Hill: Facilities Planning Planroom, 2003).

[3] J. Marshall Bullock. “Hopkins, Samuel (fl. 1790s)” North Carolina Builders & Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 2009, http://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000093 (accessed 11/19/2017)

[4] Documenting the American South. “Letter from Joseph Caldwell to John H. Hobart, November 8, 1796.”

http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/unc02-19/unc02-19.html (accessed 12/2/2017)

[5] Documenting the American South, The First Century of the First State University

http://docsouth.unc.edu/global/getBio.html?type=place&id=name0000862&name=Person%20Hall (accessed 11/19/2017)

[6] Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932 (Reel 1), p 245-246. Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[7] Letter from William R. Davie to John Haywood, February 9, 1797.

http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/unc02-17/unc02-17.html (accessed 11/19/2017)

[8] Documenting the American South. “Person Hall.” http://docsouth.unc.edu/global/getBio.html?type=place&id=name0000862&name=Person Hall (accessed 11/19/2017)

[9] Powell, The First State University, 23.

[10] Marguerite E. Schumann, First State University: A walking guide (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 40.

[11] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill: A history of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 35.

[12] Gladys Coates. “The Story of Person Hall.” Bulletin of Person Hall Art Gallery 3, no. 2 (1943), 3.

[13] National Register of Historic Places. “Person Hall,” (Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill Historic District Boundary Increase and Additional Documentation, OR1750), 13-14.

http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/OR1750.pdf (accessed 11/19/2017)

[14] Coates, “The Story of Person Hall,” 5-6.

[15] Address Delivered Before the Dialectic Society at Chapel Hill, 1836 or 1847: William C. Hooper

http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/unc05-25/unc05-25.xml (accessed 11/28/2017)

[16] Address Delivered Before the Philanthropic and Dialectic Societies at Chapel Hill, June 27, 1827: Archibald D. Murphey.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nc01.ark:/13960/t0ns1jf0f;view=1up;seq=28 (accessed 11/19/2017)

[17] Address Delivered Before the Philanthropic and Dialectic Societies at Chapel-Hill June 20, 1832: William Gaston

http://docsouth.unc.edu/true/gaston/gaston.html (accessed 11/19/2017)

[18] Steven Weeks, Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present, Volume 7, Edited by Charles L. Van Noppen, (Publisher unknown, 1908), 380-398.

http://www.accessible.com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/accessible/docButton?AAWhat=builtPage&AAWhere=BNC000602.THOMASPERSON.xml&AABeanName=toc3&AANextPage=/printBrowseBuiltPage.jsp (accessed 12/3/2017)

[19] Sue Dossett Skinner, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Edited by William S. Powell, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/person-thomas (accessed 11/19/2017)

[20] John H. Wheeler, Historical Sketches of North Carolina from 1584 to 1851, (1851), p. 162.

https://archive.org/details/historicalsketch00whee (accessed 12/2/2017)

[21] Skinner, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography.

[22] Skinner, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography.

[23] Skinner, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography.

[24] Weeks, Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present.

[25] Weeks, Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present.

[26] Weeks, Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present.

[27] Russell Phillips, These Old Stone Walls. (Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill Historical Society, 1972), 45-46.

[28] Kemp P. Battle. An Address on the History of the Buildings of the University of North Carolina, by Kemp P. Battle, LL. D, President of the University, Delivered on University Day, 1883, in Gerrard Hall: Electronic Edition.

http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/battle/battle.html (accessed 11/19/2017)

[29] Weeks, Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present.

[30] Sallie Walker Stockard. The History of Alamance. (Burlington, NC: Alamance County Historical Museum, 1986), 53.

[31] Battle, “An Address on the History of the Buildings of the University of North Carolina.”

[32] Weeks, Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present.

[33] Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932 (Reel 1, Volume 15). Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[34] Kapp, Person Hall Campus Preservation Survey.

[35] Coates, “The Story of Person Hall,” 7.

[36] Kapp, Person Hall Campus Preservation Survey.

[37] Kapp, Person Hall Campus Preservation Survey.

[38] Kapp, Person Hall Campus Preservation Survey.

[39] Coates, “The Story of Person Hall,” 9.

[40] William T. Moye, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Edited by William S. Powell, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979).

https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/arrington-katherine (accessed 12/2/2017)

[41] Commemorative Landscapes, Memorial to Founding Trustees, UNC (Chapel Hill)

http://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/23/ (accessed 12/2/2017)

[42] Kapp, Person Hall Campus Preservation Survey.

[43] National Register of Historic Places, Person Hall.