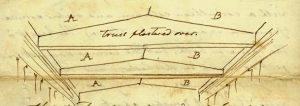

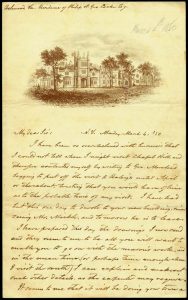

On March 4, 1850 Philadelphia architect Alexander Davis wrote to UNC President David Swain of then Smith Hall, now Playmakers Theater, stating, “It seems to me,” he said, “that it will be doing your town a great wrong to copy any building that you already have in it.”[1] Davis went on in detail about the planned exterior design, specifying “I have therefore made a front, still similar to the church, but lighter in the details… The height is the same in both, but the cornice does not project so much in the latter, and there might be four columns instead of two.”[2] The letter continues on with illustrations of the building’s plans as Davis notes the most economical ways to achieve this break within town architectural tradition. He suggests that the university should discard the original plan with an arch and skylight for a simple, fresh Classical look.[3]

On March 4, 1850 Philadelphia architect Alexander Davis wrote to UNC President David Swain of then Smith Hall, now Playmakers Theater, stating, “It seems to me,” he said, “that it will be doing your town a great wrong to copy any building that you already have in it.”[1] Davis went on in detail about the planned exterior design, specifying “I have therefore made a front, still similar to the church, but lighter in the details… The height is the same in both, but the cornice does not project so much in the latter, and there might be four columns instead of two.”[2] The letter continues on with illustrations of the building’s plans as Davis notes the most economical ways to achieve this break within town architectural tradition. He suggests that the university should discard the original plan with an arch and skylight for a simple, fresh Classical look.[3]

Letter From Alexander J. Davis to David L. Swain

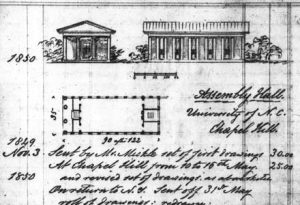

Built in the manner of Greek Revival style or “National style”[4] after Greek Athenian temples,

Smith Hall was constructed with a portico, four rounded columns, and a gable-front floor plan (gable end facing the street, representing a simple Greek temple).[5] Davis’ plans for Smith Hall placed it as the only building on campus that deviated from traditional American style structures in exchange for a unique, extravagant and classical aesthetic.[6] Yet, Smith Hall’s extravagant facade broke with the rest of the campus’ building designs as the idea of ornamentation and prestige was more closely associated with its namesake, original UNC trustee and former governor of North Carolina, Benjamin Smith.

Benjamin Smith was both and honorable and dishonorable man; a celebrated Revolutionary war veteran and also the largest recorded slave owner in North Carolina during the nineteenth century. While the purposes and uses of the building named for him have changed several times over the course of 170 years, as the oldest building on campus dedicated to the arts, the building continues to change to the present day.

Letter From Alexander J. Davis to David L. Swain

Letter From Alexander J. Davis to David L. Swain

Smith Hall: Jack-of-All-Trades

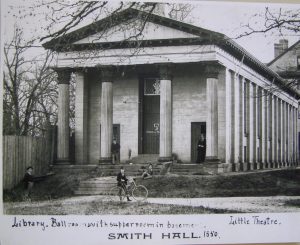

Located on Cameron avenue, next to South Building and across from Old East, Smith Hall was constructed beginning in 1850 and completed in 1852. It cost just over $10,300.[7] Originally designed as an assembly room, the building also served concurrently as a ballroom and library in 1852– a space dedicated to bringing people together for both academic endeavors and entertainment.

However, its library/ballroom days were brief, though. They were followed by a span of years in which it served many purposes and housed several departments.[8] From 1907-1924, Smith Hall was transferred twice to UNC’s Law School and agricultural chemistry department. In 1924, the building was passed on to the Carolina Playmakers, founded by UNC professor Frederick Koch. Using both state appropriations and a private donation from the Carnegie Foundation, the building was remodeled and transformed into a theater by 1925. Smith Hall was renamed to Playmakers Theater.[9] By 1936, Playmakers Theater housed the Department of Dramatic Arts until the section outgrew the space, leaving it as the university’s main theater for indoor performances. Almost fourty years later, in 1974, the theater was designated a National Historic Landmark.[10]

There are, of course, unverified rumors of the building’s use, which have circulated over the  years across campus by UNC students. Urban legend has it that the building housed Union cavalry horses from Michigan in the following weeks of the Civil War. However, Harry McKown of Wilson Library’s ‘North Carolina Collection’ has stated that there is no documentation to support this claim. However, despite that lack of documentation, students continue to relay the folklore associated with the theater. Nevertheless, one cannot deny that the building’s variety of residents certainly makes for an interesting history of occupation with or without the stabling of horses.[11]

years across campus by UNC students. Urban legend has it that the building housed Union cavalry horses from Michigan in the following weeks of the Civil War. However, Harry McKown of Wilson Library’s ‘North Carolina Collection’ has stated that there is no documentation to support this claim. However, despite that lack of documentation, students continue to relay the folklore associated with the theater. Nevertheless, one cannot deny that the building’s variety of residents certainly makes for an interesting history of occupation with or without the stabling of horses.[11]

Just as the ever-changing occupancy of Playmakers Theater is impressive, the same can be said of the theater’s alumni. The theater’s most notable Carolina alumni are Thomas Wolfe and Andy Griffith and both have performed on the theater’s stage a number of times.[12]

Origins of Design

Original plans for Smith Hall emerged after United States President James K. Polk visited the UNC campus in the spring of 1847. University officials were concerned that there was no campus building extravagant enough to receive important figures. Likewise, students had petitioned the Board of Trustees in 1833, which was rejected, and each year thereafter for a building that could serve as a ballroom. After fourteen years their request had finally been granted under the circumstances that the building also function as a library.[13]

Designed by renowned New York architect Alexander Jackson Davis of New York, Playmakers Theater has always garnered attention due to its eye-catching facade. The front portico is adorned with Greek Corinthian columns topped with North Carolina’s staple crops, wheat and corn, instead of the traditional acanthus leaves of Classical Greece. The interactive tour of Playmakers Theater indicated that the change in the Corinthian capital was a response to “the aggressive Americanism then present in the country” and, therefore, in an effort to connect the building with Southern American culture the incorporation of the crops was solidified into the hand-carved columns.[14]

Designed by renowned New York architect Alexander Jackson Davis of New York, Playmakers Theater has always garnered attention due to its eye-catching facade. The front portico is adorned with Greek Corinthian columns topped with North Carolina’s staple crops, wheat and corn, instead of the traditional acanthus leaves of Classical Greece. The interactive tour of Playmakers Theater indicated that the change in the Corinthian capital was a response to “the aggressive Americanism then present in the country” and, therefore, in an effort to connect the building with Southern American culture the incorporation of the crops was solidified into the hand-carved columns.[14]

Davis stated in his letter to Swain that the design of Smith Hall was similar in design to southern churches, but not as simple due to its “richer” details.[15] Likewise, to enhance the elegance of the front entrance Davis suggested extending the front cornice and adding four columns spaced approximately four feet apart to project a larger opening.[16] By doing so, the building would have an open-air entrance that would add height and attention to the building. Yet, the actual look of Playmakers Theater was not solely based on breaking with the routine look of the campus and city buildings; rather, the building was primarily constructed in an effort to reduce the original design, which rendered a flat exterior, but in the cheapest way possible. Furthermore, the structure was to be crafted with a front arch, but because an arch would have been too expensive on account of the labor involved, Davis opted for four columns to add aesthetic appeal and height instead of opting for the labor intensive demands of the desired arch.[17]

Namesake of Playmakers Theater

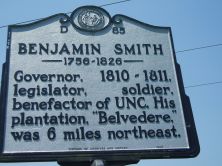

Both the university and state historical records paint the narrative behind the namesake of Playmakers Theater as a rather simple endeavor. Then Smith Hall, the building was named after Benjamin Smith, a Revolutionary soldier who fought under George Washington, a former North Carolina Governor, and one of the first trustees to the University of North Carolina.[18] A native of Charlestown, South Carolina, Smith moved to North Carolina in the late 1770s-early 1780s and settled near the coast in Brunswick County. Known for his contributions in politics, military preparedness, infrastructure improvements, education, and local government, and most notably his contribution to the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.[19]

Born on January 10, 1756, Benjamin Smith was welcomed into a family of wealthy South Carolina planters and was a descendant of well-known planter and merchant Thomas Landgrave Smith.[20] As a young boy, his education took priority. He studied under Rev. Jacob Duche in Philadelphia and, upon his return to Charlestown, continued his education under Edward Rutledge in the legal field.[21] Yet, as with many young American men in the eighteenth century the looming war took precedence and Smith, at the age of 21, was sent off to war. While serving, Smith was assigned as Aide-de-Camp to General George Washington in the retreat from Long Island in 1776 and later the same year he served with South Carolina Brigade General William Moultrie. While carrying out his orders with Moultrie, his unit was successful in pushing British enemy forces from Port Royal Island, which ultimately thwarted a British invasion of the state.[22]

Born on January 10, 1756, Benjamin Smith was welcomed into a family of wealthy South Carolina planters and was a descendant of well-known planter and merchant Thomas Landgrave Smith.[20] As a young boy, his education took priority. He studied under Rev. Jacob Duche in Philadelphia and, upon his return to Charlestown, continued his education under Edward Rutledge in the legal field.[21] Yet, as with many young American men in the eighteenth century the looming war took precedence and Smith, at the age of 21, was sent off to war. While serving, Smith was assigned as Aide-de-Camp to General George Washington in the retreat from Long Island in 1776 and later the same year he served with South Carolina Brigade General William Moultrie. While carrying out his orders with Moultrie, his unit was successful in pushing British enemy forces from Port Royal Island, which ultimately thwarted a British invasion of the state.[22]

After Smith’s honorable service with the military, he moved to North Carolina and began his career in politics. Smith was first elected as Representative to Brunswick County in the North Carolina Senate in 1783 followed by five consecutive nominations as Speaker of the Senate, and lastly he was elected the thirteenth governor of the state of North Carolina in 1810, for just one year.[23] His governorship focused on the reformation of North Carolina’s criminal codes and its penitentiary system but because of his short time as governor, just one year, he was unable to accomplish much of what he set out to achieve.

Smith as UNC Trustee

With a lifelong interest in education, politics and on account of his known wealth, Smith was appointed to the board of trustees of UNC in 1789. He served on the university board until 1824.[24] On December 18th, 1789, at the first meeting of the board, Smith became the first donor of the university, donating 20,000 acres of land in what was then Tennessee, as an endowment. The land was his payment for his “distinguished services in the Revolution” and he turned over the land warrants to UNC at the second board meeting in 1790.[25] Unfortunately, the land was located on a fault line and was involved in the New Madrid Earthquake, causing great difficulties in the sale of the land. UNC finally sold the land to fund the construction of university buildings across campus, selling the land in the mid-1830s for seventy-five cents an acre, profiting approximately $14,000.[26] While the sale caused many issues in UNC’s system, nevertheless, the university dedicated the stunning Smith Hall to Colonel Benjamin Smith in 1851, after he had been deceased for almost twenty-five years. While the building has been recognized as one of the most beautiful and unique buildings on the university’s campus, the historical figure behind Playmakers’ namesake, however, certainly had a checkered past with highs and lows and stained with slave ownership.[27]

Of the forty individual trustees appointed to the UNC Board of Trustees, thirty of the forty were recorded slaveholders. However, it was Benjamin Smith who was recorded as having owned the largest number of slaves of all of the trustees, as well as in the state of North Carolina with just over 221 slaves.[28] Born into a wealthy family, both he and his relatives had no issues with  the buying, selling, and gifting of men, women, and children.[29] In fact, slave trading was a regular practice in the Smith family. A lawsuit recorded from July 1807 titled, “The Governor v. Henry B. Howard” noted that while serving as governor, Benjamin Smith illegally purchased a number of imported slaves into the state, contrary to the Importation of Slaves Act of 1794. While Smith claimed his innocence, court records indicated that Smith was found guilty and was required to pay a 100 pound fine for his crime.[30] His entanglement with slave ownership was not his only faux pas, as historical records detail his unlikeable character. Apparently, his behavior while at his home at Belvidere Plantation, just four miles west of Wilmington in Brunswick County, was quite horrendous. Accounts describe Smith as a loner and he was also known for his raging temper and a tendency to duel on account of any quarrel.[31]

the buying, selling, and gifting of men, women, and children.[29] In fact, slave trading was a regular practice in the Smith family. A lawsuit recorded from July 1807 titled, “The Governor v. Henry B. Howard” noted that while serving as governor, Benjamin Smith illegally purchased a number of imported slaves into the state, contrary to the Importation of Slaves Act of 1794. While Smith claimed his innocence, court records indicated that Smith was found guilty and was required to pay a 100 pound fine for his crime.[30] His entanglement with slave ownership was not his only faux pas, as historical records detail his unlikeable character. Apparently, his behavior while at his home at Belvidere Plantation, just four miles west of Wilmington in Brunswick County, was quite horrendous. Accounts describe Smith as a loner and he was also known for his raging temper and a tendency to duel on account of any quarrel.[31]

Known as a lonely and bitter man who was hell bent on his aristocratic way of life, at the time of his death Smith was deeply in debt and “hated all around.”[32] His tombstone celebrated his wife rather than him, an odd approach for the patriarchal structuring of the nineteenth century, stating “In memory of that excellent Lady, Sarah Rhett Dry Smith…Also of her husband, Benjamin Smith of Belvidere, once Governor of North Carolina, who died January, 1826, aged 70.”[33]

With Smith Hall being renamed PlayMakers Theater, the historical past of the building’s namesake has been somewhat buried by the successes of the theater over the past fifty years. Much of the press associated with the theater focuses more on the successes of their shows and the renovations to both the interior and exterior of the building.

Playmakers Theater: Present Day

From 2006-2010, Playmakers Theater was closed due to severe wear and tear over the years. However, in November of 2010, the Office of Provost and the Office of the Executive Director for the Arts funded the theater’s necessary renovations of the interior in an effort to reopen the historic landmark. The original budget proposal for the theater’s interior renovation was estimated at $8 million, but the 2008 recession hindered renovations, leaving the theater empty during the summer.[34] Not wanting the space to further deteriorate, the university came up with $225,000- just enough to make the space accessible and usable.[35] While not a full renovation, the upgrades proved beneficial and the doors were reopened in preparation for the university’s spring performances. The upgrade included a new interior paint job, the auditorium floor was replaced as well as new seating and curtains, stage lighting and sound system were installed.[36] However, the stage and backstage areas of the theater are still lacking, as they still do not have wheelchair access, nor is there assistance for those with mobility issues and/or disabilities.[37] The exterior also received repairs by architect firm Pearce Brinkley Cease & Lee, PA, included repairing and replacing “plaster using period-specific materials, repairing hand-carved wood column capitals, repairing wood columns and bases and the reglazing/rebuilding of all exterior wood windows.”[38] The theater received several small grants in addition to the monetary gift from the university to pay for some of the necessary improvements.[39]

From 2006-2010, Playmakers Theater was closed due to severe wear and tear over the years. However, in November of 2010, the Office of Provost and the Office of the Executive Director for the Arts funded the theater’s necessary renovations of the interior in an effort to reopen the historic landmark. The original budget proposal for the theater’s interior renovation was estimated at $8 million, but the 2008 recession hindered renovations, leaving the theater empty during the summer.[34] Not wanting the space to further deteriorate, the university came up with $225,000- just enough to make the space accessible and usable.[35] While not a full renovation, the upgrades proved beneficial and the doors were reopened in preparation for the university’s spring performances. The upgrade included a new interior paint job, the auditorium floor was replaced as well as new seating and curtains, stage lighting and sound system were installed.[36] However, the stage and backstage areas of the theater are still lacking, as they still do not have wheelchair access, nor is there assistance for those with mobility issues and/or disabilities.[37] The exterior also received repairs by architect firm Pearce Brinkley Cease & Lee, PA, included repairing and replacing “plaster using period-specific materials, repairing hand-carved wood column capitals, repairing wood columns and bases and the reglazing/rebuilding of all exterior wood windows.”[38] The theater received several small grants in addition to the monetary gift from the university to pay for some of the necessary improvements.[39]

Currently, PlayMakers Theatre still has no plans for renovations that would add the much needed central air conditioning for the summer months, nor are restrooms or dressing rooms being considered for the building’s modernization.

Conclusion:

Playmakers Theater is a revered historic site on the UNC campus and in the city of Chapel Hill. Attracting crowds for performances and its unique exterior beauty, the theater’s Classical look strays from its architectural surroundings. Yet, with all of its beauty, the building’s namesake casts a dark shadow over its towering Athenian columns. While the university initially named the building after Benjamin Smith, the state’s largest slave owner, they did so with intentions of honoring his military service and his generous donation. The university redeemed itself, though not for the right reasons, by renaming Smith Hall after Koch’s theater company, Playmakers Theater. Yet, as wonderful and as necessary as a renaming was, the university still needs to recognize that Smith’s generous donation rested on the success of his slave plantation, which allowed for him to donate his military pay as his plantation was thriving from slave labor. By recognizing Smith’s past, the university can educate the public about the original namesake and acknowledge that a slaveholder and illegal slave trader was involved in the financing of the university as well as the name behind the original title, Smith Hall. Future renovations on the theater will hopefully include a historiography of the building, detailing Smith’s involvement and the ways in which UNC has moved away from Smith’s legacy.

Notes:

[1] Alexander J. Davis, Letter from Alexander J. Davis to David L. Swain, David L. Swain Papers (#706), Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, (March 4, 1850), 1.

[2] Ibid., 2

[3] Ibid., 2

[4] https://architecturestyles.org/greek-revival/, {Accessed April 21, 2017}. Greek Revival became the dominant style in America between especially 1820-1850. It was consequently referred to as the “national style” due to its popularity.

[5] Ibid.

[7] www.visitchapelhill.org/listing/historic-playmakers-theater/278/ [Accessed February 25, 2017]. See also: Facelift Gets Theater back in the Act, www.unc.edu/spotlight/facelift-gets-theater-back-in-the-act/, [Accessed March 24, 2017].

[8] Gary Moss, “Two Exhibits Reveal Campus Buildings as an Integral Part of the Carolina Story,” in University Gazette, April 10, 2012, [Accessed March 25, 2017}.

[9] Cecelia Moore, “A Model for Folk Theater: The Carolina Playmakers,” 2014 Gladys Hall Coates University History Lecture, (University of North Carolina, NC; 2014).

[10] www.unc.edu/interactive-tour/playmakers-theater/ {Accessed February 24, 2017}

[11] Ibid. See Also: www.visitchapelhill.org/listing/historic-playmakers-theater/278/ [Accessed February 25, 2017].

[12] www.visitchapelhill.org/listing/historic-playmakers-theater/278/ [Accessed February 25, 2017].

[13] Moss, “Two Exhibits Reveal Campus Buildings as an Integral Part of the Carolina Story.”

[14] www.unc.edu/interactive-tour/playmakers-theater/ {Accessed February 24, 2017}

[15] Alexander J. Davis, Letter from Alexander J. Davis to David L. Swain.

[16] Ibid.,2.

[17] Ibid., 3.

[18] Historic Playmakers Theater, www.carolinaperformingarts.org/ros. venue/historic-playmakers-theater/, November 21, 2012, [Accessed February 24, 2017}.

[19] Dr. Troy L. Kickler, “Benjamin Smith,” in North Carolina History Project, northcarolinahistory.org {Accessed March 25, 2017}.

[20] www.carolana.com/NC/Governors/bsmith.html {Accessed March 26, 2017}.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Dr. Troy L. Kickler, “Benjamin Smith,” in North Carolina History Project, northcarolinahistory.org {Accessed March 25, 2017}.

[25] Collier Cobb, Presentation of Portrait of Governor Benjamin Smith to the State of North Carolina, in the Hall of the House of Representatives, at Raleigh, November 15, 1911, (the North Carolina Society of the Sons of the Revolution;, 1911), 8.

[26] Alan D. Watson, “Benjamin Smith: Remembrance and Rehabilitation,” in The Bulletin: A Publication of the Historical Society of the Lower Cape Fear, Vol. LIII, No. 1 (October, 2009), 2.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Alan D. Watson, General Benjamin Smith: Biography of the North Carolina Governor, (McFarland & Company Publishers; Jefferson, NC, 2011), 62.

[29] Ibid., 63.

[30] A.D. Murphey, North Carolina Reports: Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of North Carolina: 1804-1810, (E.M. Muzzle & Co; Michigan, 1910), 129.

[31] George Washington, “Washington Papers,” National Archives: Founders Online, (June, 1791).

[32] Watson, General Benjamin Smith: Biography of the North Carolina Governor, 31.

[33] Collier Cobb, Presentation of Portrait of Governor Benjamin Smith to the State of North Carolina, in the Hall of the House of Representatives, at Raleigh, November 15, 1911, (the North Carolina Society of the Sons of the Revolution;, 1911), 14.

[34] Ali Rockett, “PlayMakers Theater to Reopen,” in The Daily TarHeel, 11/01/2010. http://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2010/11/playmakers_theatre_to_reopen

[35] Ibid.

[36] https://www.carolinaperformingarts.org/ros_venue/historic-playmakers-theatre/ {Accessed April 20, 2017}

[37] www.carolinaperformingarts.org/ros-venue/historic-playmakers-theater/

[38] http://www.hmkern.com/past-projects/projects/smith-hall-playmakers-theater.aspx {Accessed April 20, 2017}

[39] Tariq Luthun, “PlayMakers Theater Receives Necessary Makeover,” in The Daily TarHeel, 9/20/2010. http://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2010/09/playmakers_theatre_receives_necessary_makeover