At the 2004 grand opening of the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History, director Joseph Jordan’s seven-paragraph introductory message found in the pages of the event’s commemorative program only briefly touched on anticipation for the center’s successful future. Jordan instead used the majority of his letter to pay homage to the past and recognize the sacrifices that made the center a reality:

“Today, also, we recognize the immeasurable contribution and sacrifice of those students, along with their supporters among the faculty, staff and the community, who saw the possibilities for this Center and who took it upon themselves to organize and work to see that it was built. The gravity of their concerns succeeded in creating a new consciousness in the student body, including a number of courageous and special young men and women athletes who decided their leadership off of the playing fields and courts was as important as their roles on those fields and courts. We acknowledge their sacrifices, their vision and their devotion to the idea of a Center that saw social justice as an indivisible part of University education, and Black culture and history as an important component of the American experience.”[1]

The sacrifice Jordan wrote about summarized an intense two-year struggle, from 1991 to 1993, on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. That intensity is impossible to capture within a single paragraph, and those two years cannot be fully understood without the context of the preceding decades.

When the first black students came to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1951, the four male law students lived on an entirely separate floor in Steele Building, at the time a campus residence hall.[2] That segregation, sense of displacement, and sense of being an outsider, to some degree has marked the black experience for some at Carolina for the ensuing 60 years.

After the first black undergraduates enrolled in 1955 until 1967, the campus chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was the only UNC student organization devoted to black students.[3] During the 1967-68 academic year, Preston Dobbins, described by fellow students as “a forceful and energetic black transfer student from Chicago,” and Juan Coefield from Raleigh, N.C., broke away from what they considered the “conservative” NAACP and formed the Black Student Movement (BSM)—an organization they hoped would better capture what Black Ink called the “growing feeling of ‘Blackness’ on the college campus.”[4] In 1969, the inaugural issue of the BSM’s newspaper, Black Ink, posited:

“One of the major hypothesis which permiated (sic) this group and others like them on other campuses was the feeling that nothing would ever be done without the threat of disruption and violence, and all too often state and local officials proved them right.”[5]

The threat of disruption at Carolina, particularly from fall 1991 until fall of 1993, eventually led to the groundbreaking of the Stone Center in 2001. In those two years before Carolina’s centennial, black students, faculty and staff struggled—through letters, petitions, demonstrations and at times, a lack of compromise—for a space of their own on the state’s flagship campus.

Fighting for Upendo

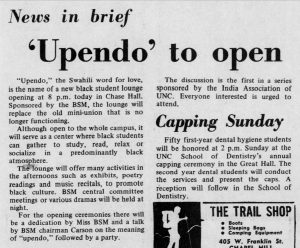

In the year after its founding, the BSM joined in a cafeteria workers’ strike, fought for a Black Studies curriculum and lobbied for increased enrollment of black students.[6] By February 1973, the BSM had secured its own space, officially celebrating the opening of Upendo—the Swahili word for love—Lounge on the first floor of Chase Hall on South Campus, where most black students at the time lived.[7] A Daily Tar Heel news brief said of the space and its purpose: “Although open to the whole campus, [Upendo Lounge] will serve as a center where black students can gather to study, read, relax or socialize in a predominantly black atmosphere.

“The lounge will offer many activities in the afternoon such as exhibits, poetry readings and music recitals, to promote black culture. BSM central committee meetings or various dramas will be held at night.”[8]

In 1974, Sonja Haynes Stone arrived at Carolina to lead the Curriculum in African American studies, for which the BSM had lobbied five years earlier.[9] Born in Chicago in 1938, Stone earned an undergraduate degree in social science from Sarah Lawrence College in 1959 and worked as a case worker at the Cook County (Illinois) Department of Public Aid and later as a community services coordinator for the Los Angeles Department of Community Services.[10] She earned master’s degrees in social work from Atlanta University in 1967 and in social and ethical philosophy from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1971.[11] While earning a Ph.D. in history and philosophy of education from Northwestern University, which she completed in 1975, Stone worked with the Northeastern Illinois University Department of Inner City Studies, serving as director, chair and assistant professor.[12]

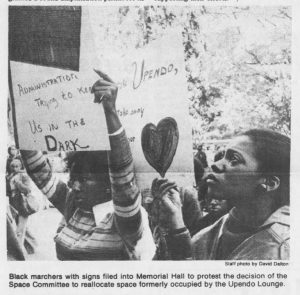

During University Day 1976, students protested the reallocation of Upendo Lounge in Chase Hall. (The Daily Tar Heel, October 13, 1976.)

While black students enjoyed some success in securing a BSM meeting space and a new curriculum, the relocation of the Chase Hall cafeteria in fall 1976 threatened their hard-won gains. Without BSM knowledge, the University’s Space Committee approved the relocation of the cafeteria from the second floor to the first, displacing Upendo Lounge.[13] While Dean of Student Affairs Donald Boulton promised space for the BSM on Chase Hall’s second floor, a rift between administration and black students emerged.[14] On University Day 1976, 200 black protesters marched outside Memorial Hall to contest the relocation of Upendo Lounge; student body president Billy Richardson protested by boycotting the ceremony.[15] The BSM demanded an apology from the Space Committee, but eventually accepted the second-floor space.[16]

In the following years, Upendo Lounge hosted Sunday morning worship services, meetings of black Greek organizations, theatrical performances about the black experience by the Ebony Readers, and performances by the Opeyo Dancers.[17] It also hosted a talk by former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader Stokely Carmichael in 1977.[18]

When Chase Hall underwent renovations in 1983, the cafeteria again took priority, occupying the entire first floor, and the Carolina Union took administrative control of the new Chase Union on the entire second floor. In the new Upendo Lounge, BSM would, the Union promised, have “priority,” but other student organizations could also reserve the space. “We will have an ambiguous term such as ‘priority’ to rely on for the existence of the BSM. It’s ridiculous,” said BSM president Sherrod Banks. “We want a new facility. It doesn’t matter a whole lot where it is.”[19]

In 1984, Boulton, the vice chancellor and dean of the division of student affairs, convened a committee to develop a proposal for a black cultural center to “promote learning, self awareness, self determination and broadened world perspectives.”[20] By January 1986, preliminary plans called for a much larger space—with room for a library, an art gallery and staff. Boulton set aside a 2,500-square-foot temporary space in the Frank Porter Graham Student Union, but BCC supporters, including Sonja Haynes Stone, wanted a commitment for a new space and an opening date.[21]

Stone’s desire to have a solid commitment for space was warranted; prior, she had struggled for her own place at UNC after being denied tenure in 1979. The denial came just when recruiting black faculty members had seemed to be a University priority. In 1977, the Ad Hoc Committee on the Recruitment of Black Faculty reported that 46 of the University’s 1,730 faculty members were black; in 1973, there had been just 14.[22] The Student Task Force for the Retention of Black Faculty, with the struggle for Upendo Lounge likely in mind, called the denial of Stone’s tenure as “a prime example of the University’s insensitivity to the needs of the black UNC community.”[23] When her tenure appeal went before a committee of the University’s Board of Trustees in 1979, 200 students marched from South Building to the Morehead Planetarium where they lined the hallways and stairs just outside of the meeting.[24] After a yearlong ordeal, votes by the Board of Trustees and then the UNC system Board of Governors granted tenure and promotion to Stone in July 1980.[25]

Boulton’s BCC planning committee issued a final report in February 1986, determining that a new center would need 8,548 square feet with a library, meeting room to accommodate 144 persons, a lounge and gallery, a music room rehearsal hall for 175 persons, offices and more. The University’s Black Cultural Center officially opened July 1, 1988, in the new temporary space in the Student Union.[26]

Loss of a leader, catalyst for a movement

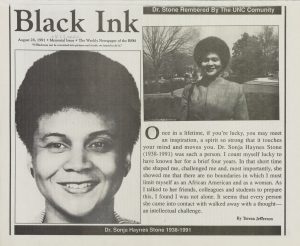

The entire August 26, 1992, edition of Black Ink was dedicated to UNC associate professor Sonja Haynes Stone.

When students returned to campus in fall 1991, they were met with the news that Stone had suffered a stroke and died on August 10.[27]

In nearly 17 years at UNC, Stone had served on numerous boards and committees, including the Black Cultural Center Planning Committee, that worked on behalf of black students and black community members, women and educators. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had named Stone its Woman of the Year in 1981. She had received the UNC Black Student Movement’s Faculty Award in 1983 and its Award for Excellent Academic Achievement in 1980. In 1990, the UNC senior class had presented Stone with the Favorite Faculty Award and the UNC General Alumni Association had honored her with the inaugural Outstanding Black Faculty Award.[28]

Colleagues remembered her as an advocate for blacks on campus and as a lifelong activist for equality. “She was a major spokesperson on campus and a social activist in the most powerful way. In the tradition of a Rosa Parks and a Harriet Tubman, she was a person who didn’t just simply talk about solving problems, she was a person who dedicated her life to strategizing and working toward solutions,” recalled Margo Crawford, director of the Black Cultural Center.[29] “She was considered very radical, and she was,” Crawford added. “If you instruct students to be award of relationships of domination and subordination, you are considered radical. If you educate black students to do more than affirm the existing racist realities that they face everyday, then you are radical.”[30]

Students remembered Stone as a teacher who made them feel their voices were heard. “She was more than a teacher to her students,” said 1991 graduate Tara L. Patterson. “She put a personal responsibility in each student. Not too many professors want to do that.”[31]

After her death, that “personal responsibility” in her students would become a collective responsibility to fight for a free-standing black cultural center on the UNC campus. Student leaders later remembered that Stone’s death catalyzed the struggle for that center.[32]

The resulting student activism quickly led to the 1991 renaming of the existing BCC for Stone.[33]

Campus views

While the renaming of the BCC came quickly, the fight for a free-standing space took much longer and divided the campus. Black Ink editor Myron B. Pitts predicted as much in a February 1992 column, and divided opponents to a free-standing BCC into four camps: the uninformed, the “pseudo-multiculturalist faction,” “the apathetic majority” and racists.[34]

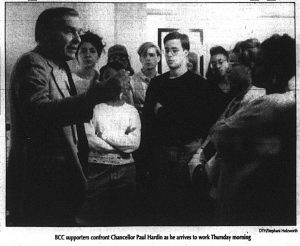

The opinion pages of The Daily Tar Heel of the time frequently carried arguments from supporters and the opposition side by side. In a March 1992 column, student Elliott Zenick, who would have fallen into Pitts’s “pseudo-multiculturalism faction,” said: “The idea of a black cultural center is a good one, but it fails to celebrate the diversity on this campus… also, a black cultural center tends to separate minority groups rather than bring them together by stating that one minority group’s existence is more vital than another.”[35] Many on campus,including Chancellor Paul Hardin, shared Zenick’s views. Adjacent, BSM president Michelle Thomas and Scott Wilkens, Campus Y co-president, countered by describing a campus where black students didn’t feel at home, even after 40 years of integration:

“Each day on this campus, African-American students must go into buildings built by their forefathers, but named for plantation owners and Klansmen. We are not suggesting that buildings be renamed, we merely wish to describe the atmosphere in which black students find themselves. Thus it is true that a free-standing BCC would give African-American students a place to celebrate their culture in an atmosphere free of intimidation found elsewhere on campus.”[36]

Faculty similarly were divided on a free-standing BCC. At its March 20, 1992 meeting, members of the Chancellor’s Committee on the Status of Minorities and the Disadvantaged—a committee of Faculty Governance—urged Hardin to “provide resources for a real, complete and excellent black cultural center,” but faculty discussions during the April 10, 1992, Faculty Council meeting revealed that several faculty members favored Hardin’s multicultural center “that would serve as ‘a forum, not a fortress.’”[37]

‘Raining revolution’

The BSM, meanwhile, increased pressure for a free-standing facility. On February 24, 1992, the group presented Chancellor Hardin with a list of demands, including a free-standing center, and asked for a response by March 11. Hardin called for yet another working group to look into the space required for an “adequate BCC”—repeating a task that the Boulton-formed group had completed years earlier.[38]

Free-standing BCC supporters marched to Chancellor Paul Hardin’s house September 3, 1992. (The Daily Tar Heel, September 4, 1992.)

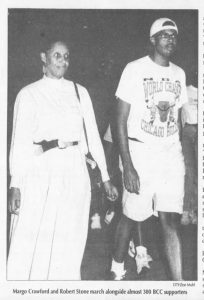

The following fall, the movement for a free-standing black cultural center intensified. On September 3 at 11:20 p.m., an estimated 300-500 BCC supporters “bum rushed” Chancellor Hardin’s home, chanting “no justice, no peace;” playing rap group Arrested Development’s “Raining Revolution;” and shining flashlights into the windows of the empty house. A week later, 300 students marched from the Pit to South Building and presented Hardin with a letter demanding his written support for a free-standing center, a location for the center and a proposal for the BOT by November 13—or, they threatened, “more direct action would be taken.”[39]

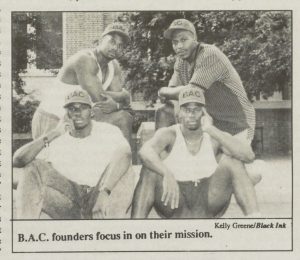

UNC football players John Bradley, Jimmy Hancock, Malcolm Marshall, and Timothy Smith formed the Black Awareness Council. (Black Ink, August 31, 1992.)

A new Black Awareness Council (BAC)—founded by UNC football players John Bradley, Jimmy Hitchcock, Malcolm Marshall, and Tim Smith—was at the heart of the fall 1992 demonstrations. A New York Times article brought the BCC struggle national attention, and showed that the black UNC football players involved were beginning to understand their unique power in the situation.[40] Tim Smith, a defensive back, said:

“It’s not common for athletes, black athletes, to be in this type of leadership role. Athletes feel they have a chance to make it, as the white man defines making it, in this society. You have a chance to go and make millions of dollars, and you don’t want to jeopardize that by speaking out about injustice.

“We feel it’s our responsibility to speak out and lead. That’s what’s surprising a lot of people. As athletes here, we have a lot of untapped power because we bring so much money into this university.”[41]

Spike Lee visited campus to support students fighting for a free-standing BCC. (Black Ink, October 5, 1992.)

The coverage drew the attention of Spike Lee and led to the filmmaker speaking to 5,000 students in the Dean E. Smith Center on September 18. During his talk, Lee urged black athletes to sit out games and jeopardize their scholarships to advocate for a free-standing BCC.[42]

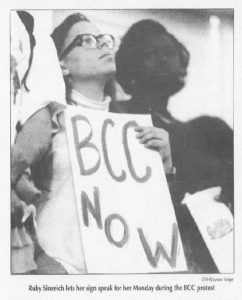

Protesters lined the walls of Memorial Hall during University Day 1992. (The Daily Tar Heel, October 13, 1992.)

With the Nov. 13 deadline still a month away, protesters interrupted University Day 1992, entering Memorial Hall after the program’s start and standing silently along the walls with signs that read “No Justice, No Peace,” “BCC Now,” “Time Is Running Out Hardin,” and “No More Waiting.” A banner that read “Hardin’s Plantation” had also appeared outside South Building during a rally earlier that year.[43] In the September 25, 1992, Daily Tar Heel reader’s forum, where Trish Merchant, a UNC education graduate, claimed that Chancellor Hardin was working to impede a free-standing center and that he had no interest in a black or multicultural center until students and donors voiced support—at which point, he felt the need to “oversee” black students on campus. “This is another tactic of the so-called civil rights white liberal enacting the master (Paul Hardin) and overseer (Provost Dick McCormick) mentally dealing with the African-American community.”[44]

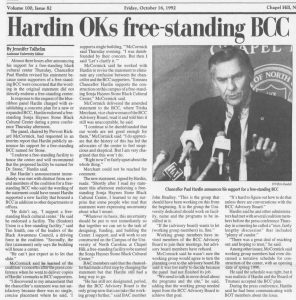

The Daily Tar Heel front page carried Hardin’s support for a free-standing BCC. (The Daily Tar Heel, October 15, 1992.)

Perhaps more pivotally, on University Day 1992, the Chancellor’s BCC Working Group, which had formed in late September and was led by Provost Richard McCorkmick, recommended that Hardin support a free-standing BCC and offered three possible locations for it: “the area between Kenan Labs and Wilson Library, the area between Coker and the Bell Tower, and the area just south of the Student Union and across from Fetzer Gymnasium.” Three days later, after months of voicing his preference for a mutlicultural center, Hardin publicly supported a free-standing BCC named for Stone.[45]

An ‘acceptable’ site for the center

Though the working group had convinced Hardin to support a free-standing center, the BCC Advisory Board refused to acknowledge the group, which included campus deans; a former BOT chair; former Charlotte mayor Harvey Gantt; Deloris Jordan, mother of UNC basketball star Michael Jordan; Sonja Haynes Stone’s parents; and UNC faculty members, students and alumni. When asked select members for the working group, the advisory board declined, pointing to a 1989 University sanction that said the advisory board should be the entity to plan for the center.[46]

However, with Hardin’s public support of a free-standing BCC, the advisory board relented and agreed to combine efforts with the working group; the BAC also tentatively lifted its Nov. 13 deadline for Hardin to name a site for the center. Whatever goodwill existed quickly ended. Margo Crawford walked out of the February 15, 1993, meeting, calling it a “farce” and saying the process lacked “integrity.”[47] In the preceding weeks, the advisory board and working group solidified programming decisions, but clashed over the building site for the center; the BCC Advisory Board favored a parcel of land between Wilson Library and Dey Hall, a site that would physically and symbolically include black history and culture at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. BCC supporters had already held a mock ground-breaking at the site during a summer 1992 rally. Working group members had no preference between the Wilson site and a site near Coker Hall and the Bell Tower.”[48]

Complicating the matter, a February 4 memo from the Departments of Physics and Astronomy detailed the need for the Wilson site as a “multipurpose science facility,” which was in line with “campus long-range land-use plans.” The following week, The Daily Tar Heel reported that University administrators supported the science complex.[49]

The working group submitted a final report for a 48,000 square-foot center that included two proposed sites, the pros and cons of both. The report stated no preference for the site, but did note that students preferred the Wilson site.[50] The advisory board rejected the working group’s proposal on account of the location and submitted its own emotionally charged proposal for a 53,000 square-foot BCC on the Wilson site.[51]

Students staged a two-week sit-in in South Building in April 1993. (The Daily Tar Heel, April 12, 1993.)

The BOT’s omission of the BCC from its March 26 agenda resulted in a sit-in in South Building, demanding Hardin call an emergency BOT meeting.[52] Hardin refused—as he watched the men’s basketball team vie for a national championship in New Orleans—and the sit-in continued.[53]

Even after two weeks of student protests in his office and at the urging of Jesse Jackson, Hardin still refused to call a special meeting of the BOT.[54] April 15, the struggle “climaxed,” and UNC saw “the first mass arrest of student protesters since the Vietnam era” as 16 students—including BAC members Tim Smith and Jimmy Hitchcock—and a Chapel Hill resident were arrested for refusing to leave the Chancellor’s office. [55]

The BOT continued to postpone a BCC decision without a location recommendation from the University Building and Grounds Committee, a group putting off decisions as well. When the committee did decide in June, it recommended the Wilson site, calling it “acceptable” and the Coker Woods site “less acceptable.” The BOT approved a free-standing BCC at the Coker Woods site during its next meeting on July 23. The Trustees cited the Wilson site’s square footage capacity as a deciding factor; it could accommodate a 100,000 square-foot building, and the BCC only called for 50,000 square feet.[56]

Continued debate

At the request of the BCC Advisory Board, the BOT heard arguments for re-evaluating the site at its September 24 meeting, but Trustees ultimately decided not to vote again.[57] Trustee Angela Bryant, who voted for the Wilson site and was one of two black trustees, voiced the frustrations of the advisory board, saying that the BCC wasn’t just about the building or even the site; it was about having a BCC on the main quad as a “symbolic acknowledgement of the importance of black culture… I’m not sure that there’s a way that the [Board of Trustees] can understand that or wants to understand that.”[58]

Despite the Trustee’s approval, the public fight over the BCC continued through fall 1993; this time, opponents leading a visible charge. John Pope, a vocal opponent of the BCC and a Trustee who had rolled off the board earlier that year, took out a full-page advertisement in Sunday, September 12 edition of The Chapel Hill News under the headline “Do You Think It’s Wrong.”[59] During the UNC Homecoming football game less than a month later, players, coaches and fans in Kenan Stadium witnessed airplanes with trailing banners that read “NO RACISM NO SEPARATISM NO BCC” during the first half and “UNC STOP BENDING OVER FOR BCC” during the second half. For BSM president John Bradley, also football team, the aerial protest was disheartening. “At a time when you’re trying to give your all to the University and you’re trying to represent the University in the best way possible…having something like that fly over really takes it out of you.”[60]

Student leaders announced acceptance of the Coker site during a November 10, 1993, press conference. (The Daily Tar Heel, November 11, 1993.)

More than two years after the death of Sonja Haynes Stone on November 10, Bradley and student groups supporting the BCC announced they would support a free-standing center at the Coker Woods site. Crawford noted the group’s. “When I look up there and see (four) white students and (two) black students, it makes me think it was worth all the work,” she said.[61]

As the University celebrated its bicentennial, black students still struggled for their reason to join that celebration—even knowing that a future University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill would include a free-standing black cultural center. Harry Amana, BCC Advisory Board chairman and a journalism professor, expressed that frustrating when the center wasn’t initially included in the Bicentennial Campaign—a multi-million dollar fundraising effort to advance campus priorities:

“The University is throwing its 200th-year birthday party, and we haven’t been invited. African Americans were never included in the University in its beginning. Here we are—celebrating 200 years of what? We’re still on the outside looking in.”[62]

Aluta Continua[63]

Even after the doors of Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History opened in 2004, more than a decade later, the struggle for space on the UNC campus continues.

In recent months, the University and other universities across America have continued to work through the very real difficulties of creating landscapes and spaces—physical and otherwise—welcoming to all students.

At UNC, we see this struggle in the Real Silent Sam Coalition and united black students’ work to create public dialogue about the buildings and monuments on campus. Those students’ work has helped to shed light on origins of Saunders Hall, since renamed Carolina Hall, and continues to inform community members about the history surrounding the memorial to UNC students who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. The group’s methods—symbolic demonstrations, protests, interrupting University Day— as well as their specific call for space on campus, recall those of the Black Awareness Council and the Black Student Movement of the early 1990s. And at universities across the U.S., we see similar struggles led by student activists.

Further discussion

The activism that led to the construction of the free-standing was well documented. The Daily Tar Heel covered the events in detail on nearly a daily basis, and Black Ink covered the events at least monthly to offer insight into the minds of student activists fighting for the free-standing Black Cultural Center. Chancellor Paul Hardin’s files concerning the Black Cultural Center are extensive and available in the University Archives at Wilson Library. The files of the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History also are in the process of cataloging for the University Archives. A deeper exploration of Hardin’s files, the Stone Center’s files and the oral histories of student activists at the time would undoubtedly yield an even richer and more nuanced narrative of the struggle for space for black students on the UNC campus.

[1] Joseph Jordan, “Message from the Director,” Milestones, August 20-23, 2004, II.

[2] “The first black law students in 1951: Harvey Beech, James Lassiter, Kenneth Lee, and Floyd B. McKissick Sr.,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed October 11, 2015, http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/integration/the-first-black-law-students-in-1951-harvey-beech-/.

“Steele Building,” Virtual Black and Blue Tour, accessed November 18, 2015,

http://blackandblue.web.unc.edu/stops-on-the-tour/steele-building/.

[3] “BSM Founding: November 1967,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed October 11, 2015, http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/black_student_movement/founding_1967/.

“BSM: Only a Start,” Black Ink, November 1, 1969, 2.

“Leroy Frasier, John Lewis Brandon, and Ralph Frasier (left to right), on the steps of South Building after completing registration, 15 September 1955.,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed October 11, 2015, http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/integration/leroy-frasier-john-lewis-brandon-and-ralph-frasi-1/.

[4] “BSM: Only a Start,” 2.

[5] “BSM: Only a Start,” 2.

[6] “BSM: Only a Start,” 2.

“The BSM’s 23 Demands: December 1968,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed October 11, 2015, http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/black_student_movement/23_demands/.

“Students Support the Food Workers,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed October 11, 2015, http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/black_student_movement/students_support_food_workers/.

[7] “‘Upendo’ to open,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 16, 1973, 2.

“Physical Space on Campus,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed October 11, 2015, http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/black_student_movement/bsm_space_on_campus/.

[8] “‘Upendo’ to open,” 2.

[9] Teresa Jefferson, “Dr. Stone Remembered By The UNC Comunity (sic),” Black Ink, August 26, 1991, 2.

“For Afro-American Studies: Program of Study Outlined,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 26, 1969, 1.

[10] “The BSM’s 23 Demands: December 1968,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed October 11, 2015, http://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/black_student_movement/23_demands/.

“About Us,” The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History, accessed September 1, 2015, http://stonecenter.unc.edu/about-us/.

[11] Jefferson, “Dr. Stone Remembered By The UNC Comunity (sic),” 2.

“About Us,” The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History website.

[12] “About Us,” The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History website.

[13] Laura Scism and David Stacks, “BSM not consulted on moving Upendo,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 5, 1976, 1.

[14] Scism and Stacks, “BSM not consulted on moving Upendo,” 1.

[15] Toni Gilbert and Laura Scism, “Black protesters join procession,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 13, 1976, 1.

[16] Laura Scism, “Space Committee passes deadline for BSM apology,” The Daily Tar Heel, November 10, 1976, 1.

Laura Scism, “BSM accepts space in Chase,” The Daily Tar Heel, December 1, 1976, 1.

[17] Mark Stinneford, “BSM angered by loss of Upendo”, The Daily Tar Heel, October 12, 1983, 1.

[18] Darrell Sharpless, “Carmichael: Socialism for Africa,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 18, 1977, 1.

[19] Joel Broadway, “Changes showing in campus dining services,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 11, 1983, 1.

Stinneford, “BSM angered by loss of Upendo”, 1.

[20] Donyell L. Roseboro, Icons of Power and Landscapes of Protest: The Student Movement for the Sonja Haynes Stone Black Cultural Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (2005), 19.

[21] Kathy Nanney, “BCC planners given no limits, still setting goals,” The Daily Tar Heel, January 24, 1986, 1.

[22] Sam Fulwood, “Recruiting continues as blacks join faculty,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 1, 1977, 1.

[23] “Stone’s tenure denial provokes criticism,” The Daily Tar Heel, November 29, 1979, 8.

[24] “A necessary commitment,” The Daily Tar Heel, November 30, 1979, 6.

Roann Bishop and Carolyn Worsley, “200 students rally for Stone; she appeals tenure decision,” The Daily Tar Heel, December 3, 1979, 1.

Beverly Shepard, “Students rally in support of Sonja Stone,” Black Ink, January 7, 1980, 1.

[25] “Playing games,” The Daily Tar Heel, July 17, 1980, 14.

[26] Roseboro, Icons of Power and Landscapes of Protest, 19.

“About Us,” The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History website.

[27] Natarsha Witherspoon, “Stone’s death marks loss of black leader,” The Daily Tar Heel, August 22, 1991, 1.

[28] “About Us,” The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History.

Jefferson, “Dr. Stone Remembered By The UNC Comunity (sic),” 2.

[29] Jefferson, “Dr. Stone Remembered By The UNC Comunity (sic),” 2.

[30] Matthew Mielke, “Campus groups name BCC, aid after Stone,” The Daily Tar Heel, August 27, 1991, 1.

[31] Jefferson, “Dr. Stone Remembered By The UNC Comunity (sic),” 2.

[32] Roseboro, Icons of Power and Landscapes of Protest, 21.

[33] Cathy Oberle, “Trustees name BCC after Stone,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 28, 1991, 1.

On October 25, 1991, the UNC Board of Trustees voted 11-1 to establish the Sonja Haynes Black Cultural Center.

[34] Myron B. Pitts, “No 40 Acres, No Mule and No BCC,” Black Ink, February 4, 1992, 2.

[35] “Free-standing black culture center debate splits campus,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 23, 1992, 9.

[36] “Free-standing black culture center debate splits campus,” 9.

[37] Jennifer Talhelm, “BCC plan supported by faculty,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 23, 1992, 1.

Jennifer Talhelm, “Faculty members discuss BCC stances,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 13, 1992, 1.

[38] “Hardin’s response irresponsible,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 12, 1992, 10.

[39] Tiffany Ashhurst, “Party in the Pit: Students March on South Building,” Black Ink, September 16, 1992, 6.

Tuere Randall, “The Shot Heard Round the World: Students Bum Rush Hardin’s House,” Black Ink, September 16, 1992, 7.

Anna Griffin, Jennifer Talhelm, and Peter Wallsten, “300 protest stance at Hardin’s house,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 4, 1992, 1.

Anna Griffin, “BCC supporters give Hardin ultimatum,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 11, 1992, 1.

[40] Renee Jacqueline Alexander, “Getting B.A.C. to Basics,” Black Ink, August 31, 1992, 5.

William C. Rhoden, “At Chapel Hill, Athletes Suddenly Become Activists,” The New York Times, September 11, 1992, PAGE.

[41] Rhoden, “At Chapel Hill, Athletes Suddenly Become Activists,” B9.

[42] AUTHOR, “Spike Lee plans visits to support BCC fight”, The Daily Tar Heel, September 14, 1992, 1.

AUTHOR, “About 5,000 rally in support of free-standing BCC,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 21, 1992, 1.

[43] Anna Griffin, “BCC protest interrupts University Day event,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 13, 1992, 1.

“Hardin Opposes Free-Standing BCC,” Black Ink, March 31, 1992, 8.

[44] “Hardin owes UNC black community an apology,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 25, 1992, 8.

[45] Justin Scheef, “BCC panel asks chancellor to OK free-standing center,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 13, 1992, 1.

Anna Griffin, “Hardin OKs free-standing BCC,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 16, 1992, 1.

[46] Ivan Arrington and James Lewis, “BCC panel to have first official meeting Oct. 1,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 25, 1992, 1.

The Chancellor’s BCC Working Group included: journalism school dean Richard Cole, former BOT chairman Robert Eubanks; former Charlotte mayor Harvey Gantt; Wendell and Doris Haynes, parents of the late Sonja Haynes Stone; student body vice president Charlie Higgins; Deloris Jordan, mother of former UNC basketball star Michael Jordan; junior Adrian Patillo; James Peacock, chairman of the Faculty Council; doctoral student Patrick Rivers; law school dean Judith Wegner; and Richard Williams, a 1975 UNC graduate and Chapel Hill manager for Duke Power.

Anna Griffin, “Center’s advocated reaffirm demand,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 13, 1992, 1.

[47] Gary Rosenzweig, “BCC panel, advisory board to join efforts,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 20, 1992, 1.

Thanassis Cambanis, “BCC design endorsed as Crawford walks out,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 16, 1993, 1.

[48] Thanassis Cambanis, “Site argument plagues BCC debate,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 3, 1993, 1.

Anna Griffin, “BCC claim on Wilson site challenged,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 8, 1993, 1.

Thanassis Cambanis, “BCC planners still debating center location,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 3, 1993, 1.

[49] Griffin, “BCC claim on Wilson site challenged,” 1.

Peter Wallsten, “McCormick denies misleading BCC advocates,” The Daily Tar Heel, February 15, 1993, 1.

[50] Jennifer Talhelm, “Report backs $6.9 million BCC, no site,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 23, 1993, 1.

[51] James Lewis, “Board splits from BCC working group,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 23, 1993, 1.

Thanassis Cambanis, “BCC ralliers take aim at trustees,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 25, 1993, 1.

Marty Minchin, “Advisory board report calls for Wilson Dey site,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 25, 1993, 1.

[52] “Johns can BCC mission,” The Daily Tar Heel, March 29, 1993, 1.

Thanassis Cambanis, “Students clog South Building,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 2, 1993, 1.

Steve Robblee, “Student BCC supporters plan to attend BOT meeting,” The Daily Tar Heel, June 24, 1993, 1.

[53] Thanassis Cambanis, “Students clog South Building,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 2, 1993, 1.

[54] James Lewis, “Jackson: Sit-in renewing ’60s fervor,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 15, 1993, 1.

Thanassis Cambanis, “Jackson: Trustees owe students action,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 16, 1993, 1.

[55] Thanassis Cambanis, “16 students arrested in Hardin’s office,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 16, 1993, 1.

Yi-Hsin Chang, “Continuing BCC debate could be resolved this summer, Compass (The Daily Tar Heel special section), June 24, 1993, 1B.

[56] Steve Robblee, “BOT postpones consideration of cultural center until June,” The Daily Tar Heel, April 15, 1993, PAGE.

Yi-Hsin Chang, “Committee recommends Wilson-Dey site,” The Daily Tar Heel, July 1, 1993, 1.

Michael Workman, “BOT Sticks to Decision On Coker Woods Site,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 27, 1993, 1.

[57] Phuong Ly, “BOT Plans To Consider Site Again,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 20, 1993, 1.

[58] Michael Workman, “BOT Sticks to Decision On Coker Woods Site,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 27, 1993, 1.

[59] Steve Robblee, “Former Trustee’s Ad Urges Opposition to BCC,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 13, 1993, 1.

[60] James Lewis, “Aerial Anti-BCC Protest Circles Football Game,” The Daily Tar Heel, October 11, 1993, 1.

[61] Michael Workman, “Students Accept Coker Site for BCC,” The Daily Tar Heel, November 11, 1993, 1.

November 10, leaders of the Black Student Movement, the Campus Y and the Student Environmental Action Coalition (SEAC) announced support of a free-standing BCC on the Coker Woods site even if it was built on a “less acceptable” site. Bradley and BSM Vice President Latricia Henry, SEAC co-chairwoman Caitlin Reed, Student Body Vice President Dacia Toll and Campus Y co-presidents Ed Chaney and Michelle LeGrand were all part of the announcement.

[62] James Lewis, “BCC Advisory Board Asks BOT to Review Site,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 13, 1993, PAGE.

Phuong Ly, “BCC Will Have to Wait For Bicentennial Funds,” The Daily Tar Heel, September 20, 1993, PAGE.

[63] Renee Jacqueline Alexander, “ALUTA CONTINUA (The struggle continues…),” Black Ink, August 31, 1992, 3.