Racism and Sexism on Campus: The Case of Spencer Hall

By Victoria Hensley

Spencer Residence Hall, although always a dormitory, has not always served both men and women. Spencer was originally a building devoted to the few women that had the ability to be a part of the University’s student body. The Women’s Building received its name in 1924. Named after Cornelia Phillips Spencer, the building itself and the namesake have histories that involve the oppression of certain groups of people. The building, with its original use as a women’s facility, traces the limited, but increasing, role of women on campus. Cornelia Phillips Spencer, although an advocate of women’s education, held racist views throughout her life. Spencer Residence Hall presents a complicated story of oppression, for not just one, but two groups on the campus of UNC.

Spencer Hall: The Women’s Building

In 1897 President Edwin Anderson Alderman persuaded the Board of Trustees to allow women into post-graduate courses; thus five women, Mary MacRae, Lulie Watkins, Cecye Roanne Dodd, Dixie Lee Bryant, and Sallie Walker Stockard, became UNC students.1 However, only Sallie Walker Stockard graduated, becoming the first woman to receive a degree from the University.

It took over sixty years after the first group of women enrolled in graduate studies at the University for women to be able to enroll as first years and sophomores, thus creating a truly co-educational campus.

Prior to the 1920s, women did not even have a dormitory on campus. In 1924 the University used appropriated funds to construct the Women’s Building.2 Before the foundation could be laid, however, controversy erupted within the Board of Trustees, who did not see a need for a building specifically for women as long as they could only apply for graduate or professional school programs.3

However, advocates of the Women’s Building argued that the University had a duty to provide its women students with a dormitory of their own. A memorandum from March 1923 stated that not to construct the Women’s Building would go against the University’s “honor”.5 A second memorandum regarding the women’s building went on to state that by not providing the building for women, the Board of Trustees would violate the charter of the University, which stated that the university was established for the education of the youth and the happiness of the rising generation, a group that included women.6

The advisor to women students (the predecessor office to the Dean of Women), Inez Koonce Stacy, also received letters advocating for the Women’s Building. Charlotte attorney Julia M. Alexander wrote Stacy twice. In March 1923, she stressed the need to pressure the Building Committee to provide the Women’s Building, which, she suggested, needed to be a beautiful, Colonial-style structure that would provide ornament to the campus.7 A little less than two months later, Alexander wrote to Stacy rejoicing at the victory of securing the Women’s Building and, again, stressing the need create a beautiful building on campus.8

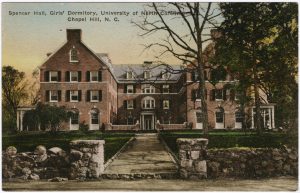

The original 1924 building had two completed floors, a dining room, kitchen, house mother’s apartment, and study.9 The third floor, finished a few years later in 1930, provided an additional nine bedrooms. The architects of the building were Atwood and Nash, and the contractors were T.C. Thompson and Brother.10 The Women’s Building received the name Spencer Hall in 1924.

The late 1950s brought about several alterations and additions to Spencer Dorm. The first proposal, from 1955, included a social room and lounge area that could accommodate a future extension. The 1955 alteration also closed a porch to make more room in the dining space.11

Meanwhile, female enrollment on campus, which increased in the 1950s, soon led to the need for more bedrooms, and an additional thirty-four double and seven single bedrooms were added in 1956.12 The 1956 addition also included a hostess suite, three baths and three toilets, an office suite, a study room, and a laundry room.13

The 1950s additions and alterations reached completion in 1958. Altogether, Spencer now had room for seventy more female students. The funds and cost for these projects totaled at $297,018.14 Harris and Pyne Architects completed the alterations and addition.15

The 1960s brought about large-scale changes in Spencer Hall. The dining room and kitchen closed; the dining room space became a study room and vending area while the kitchen became an apartment for the residence advisor.16 For a brief period during the conversion the former dining room provided office space for the Housing Department.

The changes to Spencer Hall throughout the 1960s paralleled the opening of women’s opportunities on college campuses, especially at UNC. In 1963, women students could enroll as first years and sophomores.17 Prior to this change, women could only enroll as juniors, seniors, or as students within the professional schools.

“Spencer Hall, Girls Dormitory, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC”, from UNC-CH NC Postcard Collection

Spencer Hall, although still a dormitory in 2015, no longer houses only women students. The dormitory is co-educational, with men in the first and third floor bedrooms and women in the second and fourth floor bedrooms, with the attic acting as the fourth floor. Evidence that the dormitory once housed only women students is found in the sinks that remain as an amenity in some of the bedrooms and the design of the building itself. Spencer Hall, unlike many of the other dormitories built around the same time or since, resembles a house. Looking back to Attorney Julia M. Alexander’s call for the Women’s Building to take the style of an ornamental and beautiful building, one wish did come true. The architecture of Spencer Hall is unlike any other building on campus and the house-like shape of the dormitory serves as a reminder that the building once belonged to the University’s women.

Cornelia Phillips Spencer: The University’s [Problematic] Daughter

Chapel Hill residents and historians have given Cornelia Phillips Spencer, the namesake of Spencer Hall, many nicknames. “The foremost daughter of North Carolina”, “the woman who rang the bell” and the “ North Carolina’s grown-up daughter” are just a few examples.18 However, as researchers and activists uncover more information on the University’s buildings, their namesakes, and campus history, a more complicated picture of Cornelia Phillips Spencer has emerged. Although she may be the woman who rang the bell when the University reopened after Reconstruction, she also may be the woman who helped keep the University closed by encouraging students and faculty to boycott UNC in order to force it to go bankrupt during the administrative switch. To understand Cornelia Phillips Spencer means to understand her advocacy for education, especially women’s education, but also to come to terms with her white supremacist views.

“Cornelia Phillips Spencer (1826-1907)”, from UNC-CH Southern Historical Collection

Though born in Harlem, New York on March 20, 1825, Spencer grew up in Chapel Hill. Her father, James Phillips, moved the family to North Carolina after he became mathematics and natural philosophy professor at the University in 1826.19 He purchased at least two slaves after they moved to Chapel Hill. James’s wife, Judith Vermeula Phillips ran Phillips’ Female Academy within the family home.20

Cornelia’s two brothers, Charles and Samuel, both attended the University.21 Although educated within the home with the help of her mother and professor father, Cornelia could not attend UNC, which at the time did not allow any women students. Her family’s background in education combined with her childhood in the college village led Cornelia to continue to pursue for her own education despite her inability to enter UNC. Former Governor and Senator Zebulon B. Vance once said of Cornelia, “She is the smartest woman in the State, yes, and the smartest man too.”22

Cornelia married James Munroe Spencer, a lawyer, in 1855; together they had one daughter, Julia, in 1859.23 The family lived in Alabama until James’s death in 1861. Afterwards Cornelia and her daughter moved back to Chapel Hill where the Phillips family had remained.24

Cornelia kept detailed diaries and correspondence that detailed life in Chapel Hill and at the University throughout the Civil War.25 Additionally, she kept detailed diaries on her fears and feelings about the South’s defeat in the Civil War and the Republicans’ Reconstruction that followed. In one such entry, Cornelia penned, “I look at the prospect of Reconstruction with extreme aversion, and if the Stars and Stripes wave again over our unhappy land, I for one should want to leave it forever.”26 Her diaries and many of her letters have since been turned into books or features in histories of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the University.

In regards to the University’s history, Cornelia is credited as the person who, after news hit Chapel Hill that the Republican Party no longer had control over the University, ran to South Building to ring the bell. Throughout the Civil War, the University’s enrollment dwindled and the town of Chapel Hill suffered. Cornelia, who continued to advocate for UNC, received the news that the Democratic-controlled legislature would allot appropriations for the University on her fiftieth birthday.27

“Cornelia Phillips Spencer (1826-1908)”, from UNC-CH NCC Photographic Archives

At the Class of 1888’s 39th reunion in June of 1927 suggested the idea of naming the Women’s Building after Cornelia to the university Building Committee. The reunion group proposed honoring her as the first woman to receive a degree of Doctor of Laws from a southern institution (the degree was honorary), as the self-constituted press agent for the cause of reopening the University, and as she had “one of the noblest endeavors in the history of higher education in the U.S.”28 The Board of Trustees passed this resolution without dissent.

As the 20th century drew to a close, however, a closer examination of Cornelia’s personal writing led Chapel Hill citizens and University affiliates to question her views, especially in regard to race relations. Eventually, her role as a white supremacist led to the questioning of her place of honor in the University’s history.

The Spencer Bell Award, the now retired award that honored a distinguished woman on campus each year, was the focus of controversy in late 2004 and early 2005. Since the establishment of the award, twelve women had received the honor.29 Yet, in 2004 Chancellor James Moeser found that many women he believed fit for the award said they would not accept it if offered, so the Chancellor decided to retire it.30

This decision then led to backlash from Cornelia’s descendants. The Spencer Love family, in direct response to the retirement of the Spencer Bell Award, requested that Chancellor Moeser either reconsider the retirement or have Spencer’s name removed from Spencer Hall; the family also threatened to break all ties to the Center for the Study of the American South.31 The last private owner of the house, Spencie Love, came from the direct line of Cornelia’s descendants as she is her great-granddaughter; the family helped finance the conversion of the house from private residence to research center.32

The controversy was resolved after Chancellor Moeser held a private meeting with the Spencer descendants. Moeser explained that he saw the award as representing “a specific moment in history” and decided that an award to honor Cornelia’s descendants would not only help alleviate tensions between the family and the University, but also recognize their commitment to UNC.33 The retirement of the Spencer Bell Award also meant that Cornelia would not undergo scrutiny each year in preparation for the award.

In more recent years students activists turned their attention to Spencer Hall. Efforts to contextualize racist buildings and monuments on campus led activists to the building named after Cornelia. A look into her own writing provides evidence of her guiltiness as a white supremacist.

“…but with three or four millions of enfranchised slaves, a population that is even now hastening to inaugurate the worst evils of insubordination, idleness, and pauperism among us, what hope for us unless the Northern sense of justice can be aroused into speedy action!”

“What God means for the black race, who can foresee. The change has come in their civil status. We at the South have nothing to crow over for these unfortunates.”

“‘All men created free and equal!’ Never has there been a greater misstatement. All the races of men are as unequally placed, and as unequally gifted with this world’s goods, as the individuals; and it would be impossible to reconcile these frightful irregularities with our belief in superintending beneficent Providence…”

“The withdrawal from our colored people of the sympathy, and kindness, and protection shown them by the white population of the South at the present time, will be a frightful loss to them. The setting up of one race to demand as a right what it is impossible for the other race ever to admit, is inaugurating a train of evil consequences to fall on the poor negro’s head mainly.”

Through her own words readers can infer how Cornelia felt about people of color, the enslavement of these people, and the despair she felt after the South’s defeat.34

“Spencer Residence Hall”, from Facilities Services, UNC-CH

The Two Sides of Spencer Hall

Spencer Hall, the original Women’s Building named after Cornelia Phillips Spencer, represents a challenge for UNC. First, the building’s original function as the campus’s only women’s building portrays the limited resources allocated to and spent on women at the University. Furthermore, tracing the history of the building also traces the history of college women – from the early days of a required house mother to the fight against in loco parentis, to the call for co-educational facilities. Second, Spencer Hall presents the challenge of embedded white supremacy with Cornelia Phillips Spencer as the namesake. Two groups, people of color and women, have a history of oppression at UNC and college campuses across the nation. To look more in depth at the history of Spencer Hall means to look more in depth at the histories of the university’s relationships to these two groups.

Notes

[1] Patty Courtright, “Brief encounter triggers 100 years of women students at Carolina,” UNC-CH News Services, October 10, 1997, http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/oct97/100.html.

[2] Rachael Long, Building Notes, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Updated and rev.(Chapel Hill: Facilities Planning and Design, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1993), 529.

[3] Board of Trustees Minutes V. 12, 22 November 1922, Reel 4, Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932, University Archives, Wilson Library.

[5] Memorandum Concerning a Building for Women, 7 March 1923, Box 1, Folder 19, Records of the Dean of Women, University Archives, Wilson Library.

[6] Memorandum – State University Policies in North Carolina Concerning Women Students, 14 March 1923, Box 1, Folder 19, Records of the Dean of Women, University Archives, Wilson Library.

[7] Julia M. Alexander to Inez Koonce Stacy, March 17, 1924.

[8] Julia M. Alexander to Inez Koonce Stacy, May 2, 1924.

[9] Rachel Long, Building Notes, 529.

[10] Long, 529.

[11] Alterations and Additions to Spencer Hall, 21 December 1955, Box 2, Folder “Add. to Spencer Hall,” Records of the Construction Administrative Department, 1946-1992, University Archives, Wilson Library.

[12] Addition to Spencer Hall (Women’s Dorm), 23 February 1958, Box 2, Folder “Add. to Spencer Hall,” Records of the Construction Administrative Department, 1946-1992, University Archives, Wilson Library.

[13] Addition to Spencer Hall (Women’s Dorm).

[14] Long, 530.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Courtright.

[18] See The Woman Who Rang the Bell by Phillips Russel, Cornelia Phillips Spencer: the foremost daughter of North Carolina and the Contradictions of a nineteenth-century public life by Annette Cox, and The Grown-Up Daughter: the case of North Carolina’s Cornelia Phillips Spencer by William A. Link as examples.

[19] Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, ed. William S. Powell (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), http://docsouth.unc.edu/browse/bios/pn0001360_bio.html.

[20] Elizabeth B. Dickey, “Spencer, Cornelia Phillips,” American National Biography Online. February 2000. http://www.anb.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/articles/16-16-01548.html.

[21] Dickey, “Spencer”

[22] Zebulon Baird Vance, My Beloved Zebulon : the Correspondence of Zebulon Baird Vance and Harriett Newell Esp,. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971), xxiii.

[23] Dickey, “Spencer, Cornelia Phillips.”

[24] Ibid.

[25] See The Cornelia Phillips Spencer Papers located in the Southern Historical Collection at Wilson Library for many of these papers.

[26] See Old Days in Chapel Hill by Hope Chamberlain and The Last Ninety Days of the War in North Carolina by Cornelia Phillips Spencer as examples.

[27] “Cornelia Phillips Spencer,” NCPedia.org, accessed October 19, 2015, http://ncpedia.org/biography/spencer-cornelia-phillips.

[28] Long, 530.

[29] “Moeser Retires Award Named for Spencer,” Carolina Alumni Review, December 16, 2004, https://alumni.unc.edu/news/moeser-to-retire-award-named-for-spencer/.

[30] Jenny Rubby, “Family protests award’s demise,” Daily Tar Heel, January 12, 2005, http://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2005/01/family_protests_awards_demise.

[31] Jenny Ruby, “Family protests award’s demise.”

[32] David R. Godschalk, The Dynamic Decade: Creating the Sustainable Campus for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2001-2011. Chapel Hill: (University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 73.

[33] Jenny Ruby, “Award panel will look inward,” Daily Tar Heel, January 21, 2005, http://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2005/01/award_panel_will_look_inward.

[34] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, The Last Ninety Days of the War in North Carolina (Wilmington: Broadfoot Pub. Co., 1993), 72; Chamberlain, Old Days in Chapel Hill; Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Young Lady’s Column,” N.C. Presbyterian, February 26, 1875, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/vir_museum/id/313.