By Kimberly Oliver

Situated near the northwestern edge of UNC’s campus, Swain Hall is often seen as an unremarkable building that bears the name of a remarkable man. It stands as a second-class monument to a man who the university adored and then scorned. It is far from being a campus landmark yet has served several versatile and important functions since its construction. Swain Hall received its name from the contentious Civil War-era University President David Lowry Swain, a president with an unusual lack of scholarly achievements but who cared for a university with a rising national prestige. Swain Hall represents the progressive spirit of the university as it was built to accommodate a growing student population and was later the first home of the emerging communications department.

“A Man of the World”: David Lowry Swain

University President David L. Swain[1]

Following the death of University President Joseph Caldwell in 1835, Governor Swain began to inquire about replacing acting President Elisha Mitchell and becoming Caldwell’s successor.[6] Having served as a university trustee since 1831 and being a well-known man throughout the state, Swain ran unopposed and was approved despite his lack of scholarly achievements.[7] According to Cornelia Spencer, the people of the state remarked that “North Carolina had always done a great deal for David L. Swain and now she had sent him to the University to get his education.”[8] Rather, he was “elected on account of having been by his talents and winning manners, a wise, energetic, successful administrator in the high public offices to which he had been elected.”[9] He was appointed as the second University President on December 5, 1835.[10]

Throughout his antebellum administration, Governor Swain focused on the growth of the university in the size of the student body, the institution’s prestige and influence, and the physical appearance of campus. In this way Swain demonstrated his political background in placing university culture and standing over the support of scholarship.

Undated illustration of an antebellum Old West building93

Cornelia Spencer wrote in her reminiscences “that he believed in numbers was very apparent,” a feature fundamental to Swain’s campaign to increase university enrollment.[11] Due in part to the growth of the North Carolinian upper class and their financial means, the student population continued to grow from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the Civil War.[12] Additionally, Swain attempted to extend the boundaries of the university by “encouraging admission of poor boys free of tuition and room rent.”[13] He believed also that the university should not favor one political party over the other, instead that “the university was for the sons of all parties.”[14] Swain’s friendly associations with students are well-remembered. Nicknamed “Old Bunk,” he would visit students’ rooms to socialize with them, especially seniors of which he was particularly fond, making an “atrociously bad” pun before leaving.[15] Swain was a lenient disciplinarian, believing that “for the young there was always hope, and he shrank from branding a young life with the sentence of expulsion or dismission in disgrace from college.”[16] He was accepting of the misbehavior and flaunting of university rules that were a fundamental part of antebellum campus culture, merely confiscating playing cards when they were found and in the cases of more serious infractions “Swain was thinking of the parents at home- the anguish and mortification there-and the ruined boy’s return to them.”[17] By the dawn of the Civil War, the university had the second largest student body in the country.[18] Swain’s successful campaign for enrollment, encouraged by his friendly relations with students, “had helped lift the university from the status of a small, provincial academy toward national reputation.”[19]

Along with this growth in the university’s standing, Swain directed several types of physical improvements on campus. One of the most prominent projects was the construction of rock walls around the campus grounds. Directed by Elisha Mitchell and built by his slaves, the walls were built from 1838 to 1843 with the intention of keeping livestock out and improving the aesthetic of campus.[20] Mitchell was paid $500 “for his expenses and the work of his servants.”[21] The expansion of the student body required the construction of two new residence halls, New West and New East, library and ballroom Smith Hall, as well as additions to Old West and Old East.[22] Swain hired architect Alexander Jackson Davis to design each of those projects, and continued the university’s relationship with Davis afterward, using his expertise to further curate the campus’s Romantic aesthetic.[23] The planting of trees and gardens beautified the grounds and helped create a precedent for the traditional appearance of campus that continues to today.[24] Swain’s administration was the beginning of the “stucco tradition” for building facades, with the president writing he was “about to change the dull aspect of the college edifices’ by coating them with a tinted mixture of cement, lime, and water.”[25] Swain realized the extent to which he modified campus, and stated that no further buildings would be added to the south and east.[26] He also wished to keep dormitories isolated, and prohibited roads from coming through campus.[27] Swain’s administration continued to build the university’s antebellum prestige through physical campus improvements to reflect the university’s growth and modernity.

While the university grew in standing during Swain’s administration, contemporaries commented on its decreasing scholastic standards. The concerns over Swain’s lack of academic qualifications and focus seemed to be coming to fruition. Though Swain himself was acquainted with the classics and state history and taught several senior recitations, he is criticized as being “indifferent to science and the general problems of scholarship.”[28] Snider notes that “scholastic standards were low” and theorizes it was an attempt to attract more students with the giving of “easy degrees”.[29] Swain placed the university library in the attic of South Building and did not add any new books to the collection for twenty years.[30] University curriculum focused on preparing students to be public leaders, with classes in law, history, economics, logic, and rhetoric, among others.[31] When it came to his faculty, Swain expected the loyalty he had become used to in politics. He “consulted the faculty about matters before acting, but was annoyed when they differed from him.”[32] Similarly, Spencer noted that the first thing Swain did upon taking office was to “put himself en rapport with the Board of Trustees so as to feel quite sure of their support in all cases” and to secure “the entire control for himself and his colleagues of the domestic management and discipline of the Institution.”[33] Though as stated previously Swain did not believe the university should be entangled with present state politics, he did believe its purpose should be to prepare students to become participants in those politics and tailored academic studies to that goal.

With the dawn of the Civil War, Governor Swain became more of a divisive figure in state politics, beginning to lose favor with the governing elite until he was removed from his office and outcast from the university. The chain of events that lead to this demise began with his unionist position before secession.

David Swain was a slaveholder. In 1850 he is recorded as owning nineteen slaves, a number that expanded to thirty-two by 1860.[34] Kemp Battle attributes this expansion to the fact that “his female slaves multiplied rapidly, although they did not enter into the matrimonial engagement usual among slaves.” In his dissertation Yonni Chapman interprets this statement to mean that “it is possible [Swain] discouraged family ties that might have interfered with breeding.”[35] Indisputably, slaves made up a great deal of Swain’s financial standing, placing him as “the third wealthiest man in the village” of Chapel Hill.[36] Swain’s slaveholding practices were frowned upon by his peers, who commented that his slaves were spoiled and misbehaved.[37] He owned the wife of well-known university servant November Caldwell, Rosa Burgess, and his son Wilson Swain (later called Wilson Caldwell). Swain perpetuated the university servant system, which benefited him and other slaveholders. Several of his slaves were rented to the university as servants, for which Swain was reimbursed, including Wilson Swain who was apprenticed to the university gardener after 1851.[38] Additionally, Swain seemed to have a mixed relationship with others’ slaves. He signed a letter supporting the manumission of slave Sam Morphis in 1858, yet is believed to have blocked George Moses Horton from obtaining his freedom.[39]

Despite his elite status and slave ownership, Swain was initially the head of the North Carolina Unionist faction. He led a delegation to Montgomery, Alabama, in order to persuade other southern states to attempt a proslavery compromise with the federal government, an effort that failed.[40] After Lincoln’s call for troops, however Swain switched his position and began to endorse secession.[41]

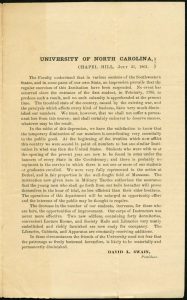

“The Faculty understands … an Impression prevails that the regular exercises of this Institution have been suspended”[42]

Throughout the war Swain fought to keep the university open despite drastic decreases in enrollment and faculty. Large numbers of students left or were drafted to become Confederate soldiers, with and without the permission of their families. Swain expressed support for the efforts of students fighting, writing that “temporary diminution of our numbers is contributing very essentially to the public good.”[43]In May of 1861 however, the president released an announcement asking all unexcused students to return to campus for their final examinations and the commencement ceremony, refusing a “suspension of duties” in order for those students to fight and clarifying that students were required to be present to receive their degrees.[44] Swain also requested an exemption of seniors from the Confederate draft and received it in 1863.[45] Despite these efforts the university struggled to remain open. The remaining faculty received decreased salaries and taught smaller classes, and the Board of Trustees operated with fewer members.[46] Swain was insistent on continuing the university’s operations, in July of 1861 issuing a memo contradicting “an impression… that the regular exercises of this Institution have been suspended.”[47]

Ella Swain[51]

The post-war university faced an even more desperate situation than it did during the war. It was under attack from all sides, with some North Carolinians calling it a “center of aristocracy and rebellion” and others denigrating it for “undue sympathy with Yankees and atheists,” a criticism rooted in Swain’s negotiation efforts. The state government decided to close the school in 1867 for reorganization, with Swain and the faculty ceremoniously resigning as part of that process.[53] Instead, Governor William Holden, part of the faction that criticized the university for its aristocratic ties, gave the administration of the university to the State Board of Education and sent state militia to secure the campus. In 1868 the board of trustees accepted Swain’s resignation, effectively firing him.[54]

Cornelia Spencer wrote about the ousting of President Swain with emotion, saying “his best friends shook their heads and were among the doubters. Even those who had eaten of bread provided by him, turned against him. But he struggled on, perhaps blindly but manfully.”[55] He was injured in an accident on August 11, 1868 while riding in a buggy pulled by a horse given to him by General Sherman and died from those injuries on August 27, with Spencer by his side. She later wrote “With him died the university, and with the university, the prosperity of the town.”[56]

An NC Highway marker found in Asheville, NC, near Swain’s birthplace[57]

Swain Hall

Not long after David Swain’s death, a memorial in his honor was proposed. The original Memorial Hall was initially planned to be named after Swain, but was later expanded to be a memorial to “all of the departed good and great- Trustees, Professors, Alumni- who have aided and honored the university.”[58] Instead, the university named a later building after President Swain in particular.

Commons Hall and Gymnasium[59]

In 1907 University president Venable called for a new student commons hall in response to the booming student population at the beginning of the twentieth century. Since 1896 the building known as Commons Hall, itself converted from the original gymnasium, had been used as a dining hall.[61] By the 1900s its capacity of 200 seats was far too small for the growing student population and Venable called for a “new Commons Hall of double the former capacity.”[62] A new dining hall was ordered by the Executive Committee on February 12, 1913 and funding came from the state’s 1914 appropriation to the university of $50,000.[63] A committee headed by Josephus Daniels was formed to create plans.[64] By using state funding for the university’s built landscape, Venable “established the principle of State responsibility for providing and maintaining the physical plant of the university.”[65]

Commons Hall Interior, 1890-1899 [60]

The site for the new building was originally chosen to be on the grounds of the Pickard’s Hotel (where Graham Memorial Hall now stands) but the Executive Committee had concerns about the ground there possibly being “spongy.” They instead decided to move the site to the location of the first President’s House, “on the north side of Cameron Avenue opposite Commons Hall.”[66] Again, this building shed light on a pattern in the campus built environment, with the issue of site location demonstrating that there was “no well-designed plan for future campus development.” President Graham would later go on to create the Committee on Grounds and Buildings to solve this issue.[67]

Construction on the building began in 1913 and the work was done by the company W.B. Barrow. The architect was Milburn, Heister and Company.[69] It continued until 1914 and the cost of the 414,000 ft3 building and equipment would total $46,654.93.[70]

Swain Hall, date unknown[68]

Few studies of Swain Hall’s architecture exist, adding weight to Archibald Henderson’s comment that “Swain Hall is so businesslike as scarcely to justify architectural comment.”[71] It is built of tan bricks in a “late medieval” style, “with stepped gable ends, a decorative front gable, windows with diamond-paned transoms and hood moldings, and an arcaded front porch.”[72] Due to its conception as a structure built to solve a university problem, the purpose of Swain Hall was practicality, not decoration.[73]

Swain Dining Hall, circa 1930[74]

Swain Hall was initially used as dining hall from 1914 to 1940. It could accommodate between 460 and 500 at its fullest capacity, and was “designed for future expansion.”[75] The building was nicknamed “Swine Hall,” a comment on the “quality of the food and the deportment of the diners” eating there.[76] Additionally, the building known as the Abernathy Annex, located next to Swain Hall, was designed to be dressing facility for those working in the kitchens of Swain Hall. It was probably built in the same year.[77] In 1924 the building caught fire, majorly damaging the kitchen and main dining room. After the renovations that followed the building was “as nearly fireproof as possible,” and could then seat 750 students in the dining room. The construction was completed by contractor T.C. Thompson and brothers and architect Atwood and Nash, and cost $11,240.86.[78] The building was reconditioned again in 1936 at a cost of $10,000.[79]

By 1940, even the enlarged building was “signally inadequate” for the demands of the student population.[80] Rather than renovating Swain Hall again, a new dining facility was built in January 1940, Lenoir Hall.[81] Swain Hall was converted to offices, and by 1946 was used by the University’s Extension Division, the Communication Center, and the Photography Library. In 1952 a transmitting tower was installed on the roof, indicating the building as the future home of WUNC radio.[82]

The UNC Department of Radio became its own entity in 1947 when it separated from the Department of Radio, Television, and Motion Picture.[83] The WUNC campus radio station was housed in in the basement of Swain Hall by 1953. The station mostly played classic music and educational programs during its three and a half hours of night sets, with one of the most popular programs being “Let’s Listen to Opera.” The music was introduced by announcers who occasionally read breaking news. Former announcer Carl Kasell remembers one instance in which a win by the basketball team over rival North Carolina State was announced during programming.[84] In 1954 fire escapes were added to the building, and the following year television channel 4 began airing from the building.[85] The hall was again renovated by architect Edward Lowenstein, AIA before it was damaged by another fire, this time thought to be set deliberately.[86]

Station Room[87]

In 1963 a 41,104 ft2 addition was added with a variety of classrooms, photography and recording studios, offices, study rooms, and heating and air conditioning. Funding for the project came from a 1959 Voter’s Bond Bill and cost $424,993.52, with the work completed by contractors King-Hunter, Inc., Thermal Equipment Company, Alliance Company, Modern Electric Company, architect Marion A. Hamm, and engineer T.C. Cooke, P.E.[88] Over the next two decades the building underwent several maintenance projects, including the addition of fire alarms, emergency exits, roof repairs, updates to the air-conditioning and electrical systems, and handicapped accessible restrooms.[89]

Beyond the physical facilities of Swain Hall, the departments that the building housed also underwent several changes. In 1986 the Corporation of Public Broadcasting reviewed the building and determined the campus radio station would not be eligible for federal grants “because of inadequate facilities.” In response, the university began raising funds for a new building to house the station at the present day Friday Center.[90] The Department of Communications similarly refused a potential donation of equipment due to space limitations.[91] In 1993 the Department of Radio, Television and Motion Pictures merged with the Department of Speech Communication to create a new Department of Communication Studies. In 2015 that entity was renamed the Department of Communication, and it continues to use Swain Hall for some of the department’s operations.[92]

Swain Hall continues to serve as a memorial to David Swain as it trains future leaders of the public, in part by housing the Department of Communication and more broadly as a part of the University of North Carolina. Though a less tangible memorial than the original Memorial Hall, the building that bears his name instead houses classrooms and is the result of Swain’s efforts to grow the university and make it survive through all manner of oppositions. The building, though named after a slaveholder and supporter of the confederacy, is not subject to the kind of campus advocacy that other Civil War era relics are at the university. David Swain was a contentious character during his lifetime, but the hall that bears his name has been significantly less controversial, a plain-looking structure that has fed, trained, and connected students at the University of North Carolina for over a century.

Further Reading:

For more information about David Lowry Swain, view the David L. Swain Papers in the Southern Historical Collection at UNC’s Wilson Library.

For more about the antebellum university, see Cornelia Spencer’s Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina, as it has been.

For a more comprehensive university history, the author recommends Light on the Hill: A History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by William D. Snider or The Campus of the First State University by Archibald Henderson.

For more information about November Caldwell and his family, listen to an interview with Edwin Caldwell, Jr. from the Southern Oral History Program.

References

[1] Swain, David Lowry (1801-1868), Portrait Collection, circa 1720-1997 (P0002): Print Box 59, Folder P0002/3249, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[2] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill: A History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (UNC Press, 1992), page 54

[3] Ruth Little, The town and gown architecture of Chapel Hill, North Carolina : 1795-1975, (Chapel Hill: Preservation Society of Chapel Hill, 2006), page 14

[4] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina,” Daily Sentinel, April 26-July 6, 1869, page 7

[5] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina. I. 1789-1868. (Raleigh, Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1907-1912), page 346; William D Snider. Light on the Hill, page 55; Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 424

[6] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 54; Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 357

[7] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 423

[8] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina,” page 34

[9] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 424

[10] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 54

[11] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina,” page 37

[12] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 59

[13] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 63

[14] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 59

[15] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 57; Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 528

[16] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina,” page 39

[17] Kemp Plummer Battle,, History of the University of North Carolina, page 528; Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina,” page 39

[18] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 64

[19] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 63

[20] Ruth Little, The town and gown architecture of Chapel Hill, page 15

[21] William S. Powell, The First State University: A Pictorial History of the University of North Carolina. (UNC Press, 1979), page 68

[22] Ruth Little, The town and gown architecture of Chapel Hill, page 17-24

[23] Ruth Little, The town and gown architecture of Chapel Hill, page 14

[24] William S. Powell, The First State University, page 76

[25] Ruth Little, The town and gown architecture of Chapel Hill, page 13

[26] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 611

[27] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 535

[28] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 424; Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 531; Marguerite Schumann, The First State University: A Walking Guide, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1972), page 40

[29] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 59; Marguerite Schumann, The First State University, page 40

[30] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 63; Marguerite Schumann, The First State University, page 40

[31] Louis R. Wilson, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University. (UNC Press, 1957), page 10

[32] Kemp Plummer Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, page 533

[33] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina,” page 34

[34] John K. (Yonni) Chapman. Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960. PhD Diss. UNC-Chapel Hill, 2006, page 19

[35] John K. (Yonni) Chapman. Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960, page 30

[36] John K. (Yonni) Chapman. Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960, page 19

[37] John K. (Yonni) Chapman. Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960, page 33

[38] John K. (Yonni) Chapman. Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960, page 21

[39] John K. (Yonni) Chapman. Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960, page 38

[40] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “The Last Ninety Days of the War in North Carolina,” (New York, Watchman Publishing Company, 1867), page 16

[41] “David L. Swain (1801-1868).” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, UNC University Archives, museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/civilwar/david-l–swain–1801-1868-.

[42] David L. Swain, “University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, July 31, 1861: The Faculty Understand That in Various Sections of the Southwestern States, and in Some Parts of Our Own State, an Impression Prevails That the Regular Exercises of This Institution Have Been Suspended, July 31, 1861.” Announcement. From Documenting the American South, North Carolina Collection. http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/unc09-84/unc09-84.html

[43] David L. Swain, “University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, July 31, 1861: The Faculty Understand That in Various Sections of the Southwestern States, and in Some Parts of Our Own State, an Impression Prevails That the Regular Exercises of This Institution Have Been Suspended, July 31, 1861.” Announcement. From Documenting the American South, North Carolina Collection. http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/unc09-84/unc09-84.html

[44] David L. Swain, “Announcement Denying the Student’s Petition by David L. Swain, May 1, 1861.” Announcement. From Documenting the American South, North Carolina Collection. http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/unc09-50/unc09-50.html

[45] Lawrence Giffin, “President Swain Requests Exemption of UNC Seniors from Conscription,” For the Record: News and Perspectives from University Archives and Records Management (blog), October 15, 2013, http://blogs.lib.unc.edu/uarms/index.php/2013/10/president-swain-requests-exemption-of-unc-seniors-from-conscription/

[46] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 67

[47] David L. Swain, “University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, July 31, 1861: The Faculty Understand That in Various Sections of the Southwestern States, and in Some Parts of Our Own State, an Impression Prevails That the Regular Exercises of This Institution Have Been Suspended, July 31, 1861”. Announcement. From Documenting the American South, North Carolina Collection. http://docsouth.unc.edu/unc/unc09-84/unc09-84.html

[48] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 68

[49] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 70

[50] John K. (Yonni) Chapman, Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960, page 49-50

[51] Eleanor Hope Swain Atkins, Portrait Collection, circa 1720-1997 (P0002): Print Box 02, Folder P0002/0089, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[52] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, Portrait Collection, circa 1720-1997 (P0002): Print Box 59, Folder P0002/3249, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[53] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 71

[54] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 72

[55] Cornelia Phillips Spencer, “Pen and Ink Sketches of the University of North Carolina,” page 36

[56] William D. Snider, Light on the Hill, page 73

[57] Marker P-5, David L Swain. North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=P-5

[58] Kemp Plummer Battle, An address on the history of the buildings of the University of North Carolina, [Chapel Hill, N.C.] : University Library, UNC-Chapel Hill, 2005, page 15

[59] Commons Hall, 1913. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, 1799-1999, Flat Box 5 Folder P0004/1058, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[60] Commons Hall, 1890-1899. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, 1799-1999, Print Box 9 Folder P0004/0225, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[61] Racheal Long, Building Notes, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (UNC Facilities Planning and Design, 1993), page 545

[62] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, 1949), page 230

[63] Arthur Stanley Link, A History of the buildings at the University of North Carolina. Honor’s Thesis. (Chapel Hill, 1941), page 175; Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 230

[64] Arthur Stanley Link, A History of the buildings at the University of North Carolina, page 175

[65] Louis R Wilson, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1900-1930, page 117

[66] Arthur Stanley Link, A History of the buildings at the University of North Carolina, page 125

[67] Louis R. Wilson, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1900-1930, page 249

[68] Swain Hall: Exterior, 1910-1959. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, 1799-1999, Print Box 17 Folder P0004/0435, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[69] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 365

[70] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 230

[71] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 344

[72] Ruth Little, The town and gown architecture of Chapel Hill, North Carolina,page 120

[73] Louis R. Wilson The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1900-1930, page 126

[74] Swain Hall: Interior, circa 1930s-1950s, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, 1799-1999 (P0004): Print Box 17, Folder P0004/0437, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[75] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 230

[76] Marguerite Schumann, The First State University, page 40

[77] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 548

[78] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 546

[79] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 230

[80] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 291

[81] Archibald Henderson, The Campus of the First State University, page 291

[82] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 546

[83] William S. Powell, The First State University, page 255

[84] Carl Kasell, interview by unknown person, April 1, 1990, from the WUNC Records, 1929-2004 (bulk 1970-1995), University Archives

[85] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 546

[86] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 547

[87] Swain Hall: Interior, circa 1930s-1950s, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, 1799-1999 (P0004): Print Box 17, Folder P0004/0437, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

[88] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 547

[89] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 548

[90] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 617

[91] Alex Japha, “The Creation of the Department of Communication Studies,” For the Record: News and Perspectives from University Archives and Records Management (blog), October 16, 2015.

[92] Racheal Long, Building Notes, page 548

[93] Old West, Undated, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, 1799-1999 (P0004): Flat Box 6, Folder P0004/1076, The North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.