“Names in Brick and Stone: Histories from the University’s Built Landscape” was produced by the students in History/American Studies 671: Introduction to Public History taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by Dr. Anne Mitchell Whisnant in 2015 and 2017 and assisted in 2015 by American Studies Graduate Research Assistant Charlotte Fryar.

In 2017, Dr. Whisnant and the students created a parallel campus history site for East Carolina University, “Legacies on the Landscape: Buildings and Names at East Carolina University.”

Please note that as of 2019, Dr. Whisnant is employed at Duke university and is no longer actively updating this site.

What Is Here and How We Created It

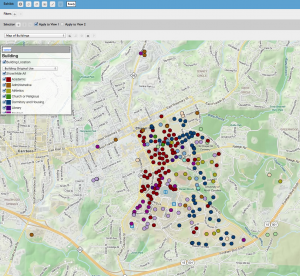

Click this image to go to our Prospect visualization containing information about over 250 major campus buildings.

To explore the histories of UNC’s buildings and their namesakes, we employ a combination of deeply researched long-form illustrated essays and a flexible visualization that assembles basic data about the over 250 structures that UNC’s Facilities Services Department classifies as “major buildings” (generally buildings over 5,000 square feet).

The visualization was built by students in the 2015 version of the course, while the 2017 students added seventeen new long essays and a set of mocked-up wayside signs in National Park Service style.

In 2015, each student selected two buildings to focus on for their essay research. In 2017, each student began with one building. These selections were not made arbitrarily, but were chosen from a larger list that represents a wide range of purposes, dates of construction, and architectural styles, and that were named for a diverse group of people.

After the selection of our buildings, students spent weeks in the archives of Wilson Library exploring records in University Archives and the North Carolina Collection to discover as much as possible about the selected buildings and their namesakes. They reviewed manuscripts, books, photographs, newspapers, Yackety Yacks, and Facilities Services Plan Room records to create as holistic a narrative as possible in a limited amount of time. They then condensed their research into narrative form. (In 2015, each student selected one of their two buildings as their primary focus, with some students writing a shorter narrative on their second building.)

Meanwhile, Graduate Assistant Charlotte Fryar developed our 250-building visualization using data collected by the students. For this part of the project, each student had to assemble certain data on about thirty buildings and twenty people for whom buildings were named.

The project assignment we worked from in 2015 may be viewed here. The assignment page contains links to many of the background materials we drew upon in both 2015 and 2017. You can learn more about the interpretive resources upon which we relied heavily for the information gathered for the visualization here.

A Longstanding Campus Conversation

Saunders, Manning and Murphey Halls, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C., North Carolina Postcards Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

Our work is the latest chapter in a longstanding campus conversation about equity and the legacies of our history that extends back at least into the 1960s.

That conversation includes labor and civil rights activism, historical research projects and conferences, numerous other class projects looking at campus histories, and conflicts and controversies around campus memorials and monuments. It encompasses quite a number of previous online, print, and in-person interpretive efforts such as those listed here. Most recently — sparked by the student activists in the Real Silent Sam Coalition — it has focused on the legacies of white supremacy embodied in the former Saunders Hall (renamed “Carolina Hall” by the UNC Trustees in 2015) and in our Confederate monument, dubbed “Silent Sam.”

These two features of our landscape have garnered significant attention, but our project expands the frame to ask several key questions:

- What does the larger network of names on our landscape say about University and North Carolina history?

- Who are the forgotten historical figures that populate our campus’s built environment?

- What stories (both told and untold) are built into our brick and stone?

- What resources (including several previous campus history projects) and new tools (especially digital ones) can let us explore them?

- How can we honestly illuminate the complex, fascinating, but also often troubling and frustrating past(s) enshrined in these structures in ways that are relevant to our aims for the present and future?

Bringing historical perspective and the tools of historical analysis to bear on present-day concerns is what public historians do. You can learn more about the field of public history and the history of this public history course at UNC here.

Yet we, as the public historians in this conversation, recognize that our voices are only a few of many, and we know that we may not have definitive answers. We have done our best, through solid historical research, to contribute something of value to the larger discussion. But we know that retold histories alone may not be enough to address the ongoing pain expressed by marginalized groups in the present.

Our Framing Ideas

Our work has been informed by several important texts illuminating the process of history and the politics of interpreting the past.

We began with Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s seminal Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1997) and concluded with Ari Kelman’s A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling over the Memory of Sand Creek (2013). These texts well frame the perspective we bring to our effort here to understand and interpret Carolina’s built landscape.

We began with Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s seminal Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1997) and concluded with Ari Kelman’s A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling over the Memory of Sand Creek (2013). These texts well frame the perspective we bring to our effort here to understand and interpret Carolina’s built landscape.

Using examples from Haitian and United States history, Trouillot unpacks the process by which “history” comes to be. He shows how “history” (the narratives we tell ourselves about the past) differs from “what happened” and how those events may have looked to people living through them. Trouillot emphasizes that the process of creating historical narratives inevitably involves amplifying some sources, voices, and events while silencing others. That sifting process, he demonstrates, always involves and reflects power. As consumers of historical narratives and archival sources, he cautions, we must always be aware of both what is said and what is not, what is loud and what is lost.

Carolina’s landscape — like most of our built environments, indeed — is a case study in the operations of power and the silencing of many pasts. The stories reflected on the landscape emerge from among many possible stories, and the landscape embodies a politics that track, in many ways, the shifting contours of power in North Carolina society. Because of that, the landscape is racialized, draped with the pall of white supremacy and patriarchal control. Yet the landscape, like any archive, like history itself, has accreted new layers over time, so its story is neither singular nor simple nor particularly coherent. It is also full of silences: stories only whispered, stories, such as the American Indian story, barely told at all. Sometimes what is not here is as important as what is here.

The visualization tool we’ve built allows us to view some of the politics embedded in the landscape. For instance, see saved “Perspective” visualizations that show:

-

- All buildings named for slaveholders

- All buildings named for individuals involved either with slavery or white supremacy and the eras in which they were built (directory & map)

- When buildings were named for white supremacists (timeline)

- The small number of buildings named for women

- Birthplaces of professors for whom buildings are named (shows regional distribution)

Our other framing book, Kelman’s Misplaced Massacre, meets us at the point of navigating competing present-day claims upon the landscape left to us by the past. It takes up the complexities of using a place to remember and memorialize the past. The book unpacks the politics of creating a National Park Service historic site at the location of the 1864 massacre of several hundred Cheyenne and Arapaho by U.S. Union troops near Sand Creek, Colorado.

Our other framing book, Kelman’s Misplaced Massacre, meets us at the point of navigating competing present-day claims upon the landscape left to us by the past. It takes up the complexities of using a place to remember and memorialize the past. The book unpacks the politics of creating a National Park Service historic site at the location of the 1864 massacre of several hundred Cheyenne and Arapaho by U.S. Union troops near Sand Creek, Colorado.

In the late 1990s, when the movement began to turn the massacre site into a federal park, another battle began — one that exposed fault lines between professional historians and archaeologists, Arapaho and Cheyenne descendants, federal officials, amateur historians and private landowners. All of these groups had markedly different ideas about where the massacre had occurred, how we should determine where the events really happened, where the memorial site should be, and what meaning and purpose the memorial should serve.

Reading about this episode, which drew to a close with the dedication of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in 2007, it is impossible not to consider the recent conversations on our campus about what histories matter now, how the histories on our landscape should reflect our current priorities and future aspirations, and how structures of power continue to press for the telling of certain histories and the quieting of others. Just as the various stakeholders contested the landscape at Sand Creek, so our own Carolina students, faculty, staff, alumni, trustees, donors and others have competing ideas about how we should understand and address the histories written and ignored on our landscape. As public historians, we have come to be comfortable with that cacophony and unresolved-ness.

An Unfinished Project

We welcome feedback, contributions, suggestions, and dialogue. This is neither a comprehensive nor a finished product. It is a digital project produced during three semesters by a group of students interested in the built landscape of their university. While we have spent a great deal of time with these buildings and people, we are not experts. We have written full narratives for only twenty-five of over 250 “major” buildings on campus. Shorter texts cover another few structures. What we have created is a working project that analyzes and supplements the longstanding conversation and presents information (both long known and newly discovered) in new ways. We hope it will point the way to other resources, information, and insights on the complicated campus landscape and social network to which we are all affiliated.

Please join us as we continue to research and understand the history of this University and its campus.

Contact Us

If you have questions or comments about this site, please contact Dr. Anne Whisnant, History 671 course instructor and site manager, at anne_whisnant [at] unc.edu.

Header image: Campus view: Richard Rummell etching, photogravures, 1907, UNC-Chapel Hill Image Collection, http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/dig_nccpa/id/2928