By Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Instructor, Introduction to Public History

The Public History Field

Interpreter at De Soto National Memorial (Bradenton, FL), December 2006. Photograph by David Whisnant.

Public History as a modern field of historical practice sits at the intersection of rigorous historical research and clear-eyed analysis and public energy around the meaning of history in the present. Or, as the National Council on Public History puts it, public history is “putting history to work in the world.” The specific places where public history is practiced can range from museums to national parks and historic sites to digital projects to historic preservation efforts, but all public historians share a commitment both to honesty about the past and to understanding how the past continues to be relevant now.

That means that public historians’ work is often responsive to and directly engaged with present-day events. The recent public spate of killings of black citizens by police and racist vigilantes, related as they are to our country’s persistent, historic racial structural inequities, have heightened Americans’ attention to racist and pro-Confederate symbolism saturating our landscape. These events have called public historians and historical organizations to consider how we should respond to divisive and painful current events and how, in fact, public history might foster efforts for greater justice and equity. Among currently ongoing public history efforts along this line, we find the #MuseumsRespondToFerguson examples discussed on Twitter, the #CharlestonSyllabus of readings and resources responsive to the killing of black parishioners in a Charleston church, and various projects related to the murder of Freddie Gray by Baltimore police.

Public History at UNC-Chapel Hill

What we might recognize as “public history” has had a long presence at UNC-Chapel Hill, although not always under the “public history” name. The Southern Oral History Program, founded by Prof. Jacquelyn Hall in 1974, has for decades sought to connect historical collecting, research, activism, and public service and has trained many undergraduate and graduate students in techniques and sensitivities of working with various publics.

Wilson Library, with its various collections, blogs, digital and outreach projects and its historical gallery, has been a center of publicly focused history work at the university for many years as well. Wilson Library, too, is the primary curator of many of the university’s previous efforts at interpreting campus history (described in more detail here). Legions of masters students in the School of Information and Library Science (SILS) have benefited from field experiences on many of these projects, and SILS for years had a joint master’s program with the public history M.A. program at North Carolina State University.

Meanwhile, under the auspices of a National Endowment for the Humanities Grant, Professor Otis Graham, three history colleagues and one business professor offered what may have been the first explicitly “public history” course at Carolina in the early 1980s. Called “History for Decisionmakers,” the class was part of the Business School curriculum and lasted only a few years. (Graham described this course in an article in the Spring 1983 issue of The Public Historian.)

Not until 2008, however, did UNC’s Undergraduate Bulletin contain a formal, permanent history course on public history. I introduced History 671 that year with a focus on the practice of history in the National Parks. The first cohort of public history students traveled North Carolina and surrounding states investigating how our region’s parks approach the histories they tell.

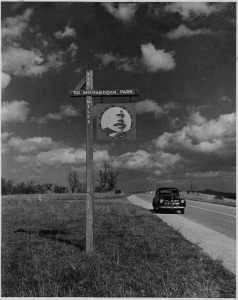

Blue Ridge Parkway near the Bluffs (Doughton Park), NC, 1946. Photograph by Abbie Rowe. From Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway. Click the image for more information.

From 2009-2014, students in the course conducted research and developed historical interpretive materials about the Blue Ridge Parkway, first for inclusion in the Driving Through Time digital Blue Ridge Parkway site that the UNC Libraries and I developed, and later for two freestanding exhibits: The Unbuilt Blue Ridge Parkway and Parks to the Side: Stories from Six Blue Ridge Parkway Recreation Areas, built in collaboration with colleagues in UNC’s Digital Innovation Lab.

As my own interests evolved, however, I began to consider refocusing the course project from the Parkway to the UNC campus. This turn reflected in part an attempt to unify what had become two rather unwieldy and out-of-phase components of the course: the Blue Ridge Parkway project and a series of tours and meetings I had always arranged with local public history practitioners. Since at least 2010, I had drawn heavily upon the expertise of the public historians practicing on and around the campus to discuss their work with the class. These professionals — historians, anthropologists, archivists, exhibit developers, historical architects — had taken the students on tours (importantly, Tim McMillan’s Black and Blue Tour) and discussed the work of campus historic preservation, campus museums and archives, history-inflected public relations, and the innovative historical exhibits developed by Kenneth Zogry at the Carolina Inn. Students repeatedly commented that this element of the course had awakened their interest in what had previously been an overlooked landscape.

From 2008-2012, meanwhile, I chaired a small committee of historians charged by the National Park  Service (NPS) and Organization of American Historians with investigating the practice of history within the NPS. Their report, Imperiled Promise: The State of History in the National Park Service, appeared in Spring 2012. One of its central recommendations was that the Park Service, a major interpreter of many parts of American history, needed to do a better job of preserving, understanding, an presenting the agency’s own history.

Service (NPS) and Organization of American Historians with investigating the practice of history within the NPS. Their report, Imperiled Promise: The State of History in the National Park Service, appeared in Spring 2012. One of its central recommendations was that the Park Service, a major interpreter of many parts of American history, needed to do a better job of preserving, understanding, an presenting the agency’s own history.

I began to see that the same admonition might be applied to the university. This realization dovetailed with my longstanding interest in the politics of power, inclusion, exclusion, and marginalization at universities based in my professional experience as an “Alt-Ac” or “altac” Ph.D. working outside the faculty as a university administrator. This perspective heightened my awareness of the university itself as an intriguing historical construction.

With all of these ideas in mind, I began to see reorienting the class project to consider the university’s history as a way to unify the courses’s efforts both to engage with campus practitioners and to produce tangible new public history work. Especially given the ongoing challenges of working on Blue Ridge Parkway projects at a great distance from both the park and most of its archival resources, this change also presented a way to develop projects for which students would find abundant primary resources and ready community interest.

Working with UNC colleagues Cecelia Moore, Tim McMillan, and UMass Amherst’s Rob Cox, I developed some of these ideas through a session on The University as a Public History Landscape at the 2014 National Council on Public History in Monterey, CA. Subsequently, Moore, McMillan, and I presented the talk to colleagues at the University of South Carolina, where the public history program had been working on campus interpretive projects related to the history of slavery at the university.

In the fall of 2014, I applied for and received a Digital Humanities Course Development Grant from the Carolina Digital Humanities Initiative to support the groundwork needed to refocus the course project on university history. This grant allowed my to employ Graduate RA Charlotte Fryar in the summer of 2015 to develop the background research materials needed for the students (and an instructor with no expertise in university history!) to embark on the study of campus building histories.

Although I had been closely following the local and national conversations about interpreting campus histories (especially around race and slavery) throughout 2014-15, I made the specific decision to focus the course project on buildings and their namesakes after my work in the Office of Faculty Governance drew me directly into the UNC Trustees’ discussions about renaming Saunders Hall and contextualizing campus history in the spring of 2015. I felt that I could use the skills that I already had with mapping, digital history, and public history to build an interpretive prototype that might provide a model of what a larger campus educational and interpretive project might look like. No matter what happens with that project, I look forward to continuing to develop this UNC history component of History 671 through the next several iterations of the class.

Meanwhile, I expect that my future work on this course will be enhanced by what I learn from colleagues on other campuses who have joined three other colleagues and me for a working group on Campus History as Public History for the 2016 NCPH meeting in Baltimore. Follow our conversations on Twitter at #CampusHistories.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the assistance and support of the following people who helped me develop this project:

- Charlotte Fryar, Graduate Research Assistant

- Michael Newton, Digital Innovation Lab, UNC-Chapel Hill (developer of the Prospect visualization tool)

- Jason Tomberlin, Sarah Carrier, and Brooke Guthrie, North Carolina Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

- Nick Graham, University Archivist, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

- Matt Turi, Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

- Judy Panitch, UNC University Libraries

- Su Song, Facilities Services, UNC-Chapel Hill

- Cecelia Moore, University Historian, UNC-Chapel Hill

- Kenneth Zogry, Independent Consulting Historian

- Dan Anderson, Carolina Digital Humanities Initiative

This class was supported by a 2015 Course Development Grant from the Carolina Digital Humanities Initiative.