A Man in the Middle: Edwin A. Alderman and Alderman Residence Hall

By: Mattea V. Sanders

On March 19, 1942, Frank Porter Graham wrote a letter to parents and students about the changes that World War II wrought at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The University became responsible for the housing of naval aviation cadets in ten of twenty-four dormitories on campus. As a result, students lived three to a room in dormitories, fraternity houses, “student co-op” houses, and private homes. The University answered the call for housing by opening three new women’s dormitories: Alderman, Kenan, and McIver. Beginning in the academic year of 1943, one hundred and forty-six girls moved into Alderman Residence Hall. Alderman Residence Hall received its name from a man who forty-six years earlier was responsible for the admittance of the first female student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.[1]

“Alderman Residence Hall, 1937” in The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click on image to learn more.

The university began building Alderman Dormitory in 1937 using funds from the New Deal’s Public Works Administration.[2] The Board of Trustees chose to commemorate Edwin Alderman in naming the new women’s dormitory, to celebrate his tireless advocacy of white women’s education in the South.[3] It has been a residence hall for the entirety of its existence — today housing 107 students on its three floors. [4] Edwin A. Alderman lived from 1861 to 1931, graduated from the University in 1882, and served as UNC President from 1896 to 1900.[5] Today, Alderman Residence Hall is a coed residence hall located on Raleigh Street between the Coker Arboretum and Battle Park on a quad with the two other dormitories, which opened at the same time. The building has three floors, five lounges, laundry room, and two kitchens for student use.

While the history of the building is straightforward, always existing as a dormitory with renovations every decade to keep the building up to date, the history of its namesake, Edwin Alderman, is far more complex. Alderman was a man responsible for the aesthetic value that is at the heart of UNC campus identity and for moving the university into a new phase with the introduction of women into the student body. What is most enthralling about Alderman is that he embodies an entire generation of white southern leadership who sought to create a new education system in the U.S. South predicated on inclusion of some and the exclusion of many.

Early History of Edwin Alderman before UNC Presidency

Edwin A. Alderman was born on May 15, 1861, in Wilmington, NC. He first received informal education from his sister Alice, before attending two private schools in Wilmington: The Burgess Military School and the Catlet School. Prior to attending college he attended Bethel Military Academy near Warrenton, Virginia.He enrolled at the UNC in 1878, just four years after the university reopened following Reconstruction. Alderman existed in an aristocratic class at UNC, renting a room at a boarding house rather than staying in a dormitory.[6] Much like the state UNC resided in, the student body of the university was divided along class and regional lines.[7] At the top of the caste system sat Alderman and other students heralding from the state’s cities.

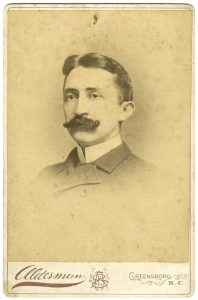

“Edwin Alderman, photograph taken upon acceptance of position at the Normal School” in Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, UNCG.

These male students joined secret fraternities, which the university faculty was hostile to due to their exclusivity. At the bottom, students such as Charles B. Aycock came from counties and belonged to democratic groups that waged war on the fraternity men. [8]

Even though Chapel Hill was a divisive place during Alderman’s student career, Alderman’s economic status afforded him many opportunities including winning the William P. Mangum Medal for his speech on “Ireland and Her Woes.”[9] It was also during this time at Chapel Hill that Alderman became acquaintances with Cornelia Phillips Spencer and was inspired by her persistent campaigning in the public press for UNC. Alderman later attributed his inspiration for women’s education to Spencer.[10] Alderman looked back at his time at UNC fondly, later remaking in an address during his time at Tulane University that “there was no better place, I think, for the making of leaders in the world, than Chapel Hill in the late 1870s.”[11]

While most of his fellow students at UNC expected Alderman to become part of the clergy or join the bar as a result of his oratory skills, Alderman became a teacher. Kemp P. Battle wrote in 1912 about Alderman’s choice to pursue a career in education:

Spurning the temptation to engage in the pursuit of riches, or political honor, he determined to devote all the energies of heart and mind and soul to the uplifting of the children of the land.[12]

He was a teacher and later on a superintendent at the “graded” schools in Goldsboro founded by J.L.M. Curry. Curry became a major mentor in Alderman’s life. Alderman and his colleagues, under the tutelage of Curry, would go on to become prominent figures in the Southern education movement and leaders in the state of North Carolina for the next forty years. These colleagues at the Goldsboro Normal School included: Charles Duncan McIver, James Y. Joyner, Charles B. Aycock, Locke Craig, Charles W. Dabney, Walter Hines Page, and Edward P. Moses.[13] It was this foundation in state sponsored education that Alderman referred back to in his many addresses for the rest of his life.[14]

During his tenure at Goldsboro, Alderman developed lasting political and ideological beliefs. In a speech given during his time at Goldsboro, he argued that the function of education was to elevate the new society of the New South. Alderman disdained the Populist movement for its idolizing of the self-made man. The Populist movement also held higher education in contempt. Alderman believed that society should be governed by educated men rather than by self-made men.[15]

It was during Alderman’s time at Goldsboro that his private life took a new turn when he met Emma Graves. Graves’ father was a celebrated schoolmaster of the post-bellum era, and her brother was a prominent UNC professor. The couple married in 1885, and soon Graves gave birth to three children who all died before the age of six.[16]

“Founders of the Normal School” in Charles Duncan McIver Records, 1855-1906, Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, UNCG.

Teacher’s Institutes

On Commencement night, June 1889, Charles Duncan McIver and Edwin Anderson Alderman stayed up until dawn drawing up a plan to develop public schools in the South. The two men saw themselves as pioneers in education evangelism. The two men received letters soon after from the State Board of Education appointing them as conductors of the State Teacher’s Institutes.[17]

The purpose of the institutes was to educate and recruit potential teachers and to attract converts to the idea of local taxation to expand the public school system. Alderman’s duties also included running a teaching training program for normal instruction for white teachers. Alderman primarily worked in Asheville and Newton. Alderman mainly focused on being a campaigner rather than a trainer. McIver and Alderman worked effectively together speaking about the importance of state-sponsored education.[18] They spoke at institutes, public meetings, and school rallies. In their first year, they traveled 3,100 miles, taught 3,600 teachers, and addressed 35,000 citizens. The State Teacher’s Institutes’ largest success was winning widespread acclaim and accolades for Alderman and McIver.[19] Alderman worked for the institutes for three years until funds dried up as a result of the return of Reconstruction issues in state politics.[20]

Alderman Takes on Southern Universities

In the years following Alderman’s service at the State Teacher’s Institutes, Alderman turned his focus towards higher education, which he believed, was wholly inadequate to educate the South’s future leaders both male and female. Alderman’s next career move, therefore, was to help to found the Normal and Industrial School for women (Normal School) (now UNC-G) and the Agricultural and Mechanical College for the Colored Race in Greensboro with Charles Duncan McIver. The Normal opened in October 1892 and served 200 students its first year. Alderman believed that the “forgotten women,” or white middle class women, were most disadvantaged in receiving education.[21] The Normal School created new gender norms as well as undermining old ones. Female students encouraged by their parents to become self-supporting, enrolled at the Normal School under the ‘promise to teach plan.’ In exchange for free tuition, they were required to teach two years in public graded schools after graduation. These graduates became disciples of the graded school movement envisioned by McIver and Alderman. In doing so, these girls coded teaching as women’s work, while administration became men’s work.[22] The establishment of the school and his future efforts towards women’s education became Alderman’s major accomplishment.[23]

“Edwin Alderman and Charles Duncan McIver with first graduating class, Greensboro, 1893” in University Archives & Manuscripts, UNCG University Libraries, UNC-Greensboro. Click on image to learn more.

Alderman worked as a teacher at the Normal for one year. Students at the Normal School commented on Alderman’s stellar teaching ability. One student wrote in the Greensboro Record in 1893 that Alderman demonstrated an “accurate knowledge, and finished scholarship, his broad conception of his subject, his attractive and eloquent method of imparting instruction.”[24] She said his “simple, strong Anglo-Saxon words could have been understood by a little child,” yet they seemed “as blocks of polished marble.”[25] It was with this strong emphasis on teaching that led Alderman to leave Greensboro to accept a position at UNC in 1893.[26]

Alderman served at UNC as custodian of the university’s gradually expanding library in addition to his faculty position. During his tenure as head of the library, he expanded the positions of the librarians, arguing that they served as more than just clerks. In an article for the Alumni Quarterly, Alderman wrote that the “modern library has become not only a storehouse of thought but a laboratory, a workshop, a mine, and inspiration for both professors and students.”[27] In his faculty position, Alderman served as the first Professor of History and Philosophy of Education.[28] Alderman stood out amongst his stoic colleagues because of his informal teaching style. A former student wrote a recollection about Alderman’s presence on campus,

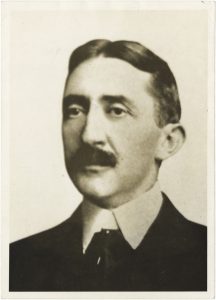

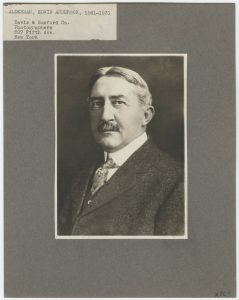

“Edwin A. Alderman (1861-1931)” North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click on image to learn more.

In a period of frock coats he wore tweeds and colored neckties. At a later time it was whispered that his clothes were made in England. Undoubtedly he was often wondered at and sometimes laughed at, but unquestionably he was admired. Some may have doubted that such a natural aesthete could really have the common touch, but he had stumped the state in behalf of untrained teachers with the gusto of a countryman.[29]

Alderman had a strong interest in history indicated by his contributions to historical journals and lecture tours throughout the state of North Carolina.[30] He is credited with introducing survey-type courses on the history of Western Civilization. He also supervised the research and writing of the first thesis ever accepted by UNC for a Master’s Degree in History. He became one of the founders of the William L. Saunders Historical Society and was appointed by President Grover Cleveland to the Board of Visitors at the Military Academy at West Point.[31]

Church vs. State Debate

Despite Alderman’s early misgivings about Populism, the movement continued to grow in the late 1880s and early 1890s. A hard economic crisis hit the state of North Carolina in the early 1890s. Farmers earned ten million dollars less than the previous year as a result of a bad cotton crop. At the same time, enrollments at denominational colleges declined.[32] Alderman took center-stage in 1895 when Populists, who had taken control of the North Carolina legislature in 1894, introduced a bill to strip UNC and the normal schools from the state budget. The Populists believed that the education system should be secular and controlled by local authorities. Populists in the legislature viewed UNC as a cosmopolitan university created by elitists.[33] While the bill was ultimately defeated, the incident left him with a lifelong desire to persuade the masses of the importance of public education.[34]

“Truth, shining, patiently like a star, bids us advance; and we will not turn aside.”[35]

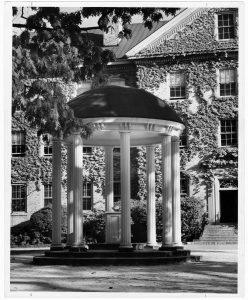

“Lamp in the shape of UNC’s Old Well,” in Carolina Keepsakes, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click on image to learn more.

On the eve of his election as President of UNC, Alderman gave an address to the National Education Association at the Atlanta Exposition in October 1895.[36] In his speech, Alderman put forth his first substantial articulation of educational statesmanship:

The mere industrial man will not answer our need. The mere orator, or politician, or scholar will not do. There must be a complex of all these-the man of free spirit and constructive habit-the man of insight and effectiveness, of utility and beauty, of action and contemplation.[37]

At this stage of our culture when millions are to be impressed with the importance of knowledge, the southern scholar must forego the office of prophet and seer and become ruler and reformer.[38]

Alderman became President of the University of North Carolina in 1896, the same year he lost his wife to tuberculosis. His beliefs and foundation in the southern education movement dictated his initiatives while President. He hoped UNC could emulate midwestern universities because of their high state appropriations; for example, Wisconsin received $273,000 and Illinois received $333,000 while UNC only received $20,000 in state appropriations.[39] He hoped that by the end of his presidency the university could guarantee broad-based state support for public education to gain larger appropriations.[40]

Alderman’s presidency at UNC is known for two major contributions: the significant alterations of the physical campus landscape and the permanent enrollment of women into graduate courses.[41] Alderman deeply believed in enlightened public education at both the secondary and university levels in North Carolina.

He built the temple around the Old Well as a visual assurance to North Carolina citizens that enlightenment was a prerequisite for any improvement of the basic system. Alderman understood how to use architecture to convey messages for practical, civic purposes.[42] The construction of the structure around the Old Well, a reproduction of the Temple of Love at Versailles, symbolizes Alderman’s ideals for the New South, that education could save the state of North Carolina.[43] Alderman wrote a letter to his niece Mary in 1923 with his testimony of his decision to build the Old Well:

“Old Well” in University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Collection, Buildings & Grounds (P4.3), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click on image to learn more.

“Treble hook, wrought iron. 1800s, from UNC’s Old Well,” in North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click on image to learn more.

Here is the history of the well as my memory holds it. In the fall of 1897, if my memory does not fail me, I was possessed with a great desire to add a little beauty (which, after all, is the most practical influence in the world) to the grim, austere dignity of the old Campus at Chapel Hill. Looking out of my window on the first floor of the South Building, I behold the old well squalid and ramshackled. I determined to tear it down and put something there having beauty. Of course, money with which to do ambitious things was utterly lacking. I had always admired the little round temples which one sees reproduced so often in English Gardens.[44]

I recall a fine shindy I had with a very distinguished professor who intimated broadly to me that I was foolish to spend money (about $200) for such luxurious gewgaws when so many vital things-sewers, water works, electric fixtures-cried out for improvement. I recall intimating to my distinguished colleague that he would do well to attend to his own ‘damn’ business.[45]

Both the Carr Building, a dormitory, and the Alumni Building were commissioned under Alderman’s presidency. Alderman helped to create myths and images of old Southern leaders such as Thomas Jefferson, Robert E. Lee, and John C. Calhoun.[46] Alderman idolized Robert E. Lee because of his accomplishments as president of Washington College (now Washington & Lee). In Alderman’s eyes, Lee was dedicated to the training of young men to be gentleman. All of the men Alderman chose to memorialize offered a model of Southern gentility born out of high economic birth and connection to elite education. Each of these men also believed in the inferiority of blacks and lower class whites.[47]

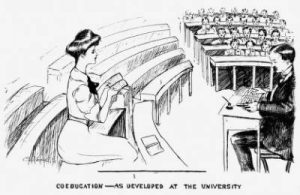

“Drawing of early female student from the Yackety Yack, 1907” in Publications Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click on image to learn more.

From Alderman’s acquaintance with Cornelia Phillips Spencer to his time teaching at the Normal School, Alderman believed in the importance of white women’s education. From the beginning of his presidency, he campaigned in front of the Board of Trustees to allow women to enroll. The Board of Trustees voted on February 21, 1897 to admit women to postgraduate courses.[48] The first five women: Sallie Walker Stockard, Dixie Lee Bryant, Mary MacRae, Cecye Roanne Dodd, and Lulie Watkins became students the following fall. Sallie Walker Stockard was the only woman of the five to graduate.[49]

Before the end of his presidency, Alderman fought once more for the preservation of state funding for UNC in the state legislature. In 1898, Democrats attempted to wrestle control from the Fusionists, and in the process, education support became tangled with the fight to maintain white supremacy.[50] Democrat Furnifold Simmons made a deal with the Kilgo-Bailey faction to oppose increased education appropriations in the 1899 General Assembly in exchange for the faction’s support for the white supremacy suffrage amendment. Alderman and McIver worked to crush this alliance and ultimately won enhanced funding in 1899.[51] Ultimately, the democrats, Alderman, and McIver would go on to gain a large win in the state with the election of Charles B. Aycock. Aycock’s election crushed the alliance between the white poor and black voters that was the foundation of Fusionist politics and ushered in the era of Jim Crow in North Carolina.

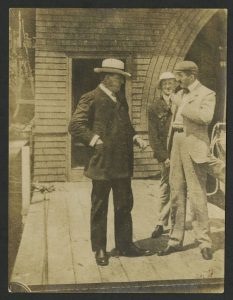

“Venable, Alderman, Graham, Battle at Graham’s Inauguration” in North Carolina Postcard Collection (P052), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click image to learn more.

Alderman Leaves Chapel Hill

In 1900, Alderman left UNC to become President of Tulane University.[52] During his presidency at Tulane, Alderman helped in the formation of the Southern Education Board (SEB). The SEB had its roots in the freedmen’s aid societies established by white churchmen during Reconstruction. The first conference was held in 1898 in Capon Springs, West Virginia.The missionary agenda of the organization quickly gave way to desires for regional reconciliation. New leadership of the organization hoped to see Southern life industrialized and to be included in the growing national economy. Alderman and others believed that the starting point for this process of reconciliation and incorporation into the nation began with education. For the next fifteen years, organization members met every spring in a different area of the South.[53]

“Edwin Alderman on the steps of Cabell Hall at the University of Virginia, 1926.” UVA Special Collections.

In 1904, Alderman was selected as President of the University of Virginia (UVA). While there, his true beliefs and goals for higher education, the state of Virginia, and the New South began to blossom. Alderman used UVA as a test case to create his ideal university structure. He increased the enrollment, created graduate programs, and established endowments.[54] Similar to his work in establishing the Normal School, Alderman attempted to create a coordinate college for women at UVA. He received strong opposition from the Board of Trustees and instead chose to establish a separate college, Mary Washington College, in Fredericksburg in 1908.[55] Late in life, Alderman wrote that he brought about change to universities in three stages:

- The first stage was to secure the interest and support of the citizens of the state.

- Second, was to persuade the state government to support applied fields of experimental research and to promote extension of the existing physical facilities of the campus.

- Third, the function of the University was to ‘advance human knowledge’ and to enlist the state in that effort. It was essential for the encouragement of original research and graduate education.

In reflecting on his career, he argued that UNC and Tulane University could not get past the first phase and that UVA only achieved the third phase near the end of his tenure as president.[56]

Conclusion

Though his life is well documented through biographies, personal records, and university archives at three major universities, it is difficult to draw an accurate picture of Edwin A. Alderman. Alderman is a man of contradictions. While he advocated for white women’s education, he also worked to create an educational system that entrenched racial, class, and gender norms. He hoped in some respects to resurrect antebellum society. Alderman often spoke about a three-tiered class structure for Southern society in which blacks and poor whites would continue to be inferior to an educated elite.[57]

“Folder 0021: Alderman, Edwin Anderson (1861-1931): Scan 1” in the Portrait Collection (#P0002), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Click on image to learn more.

Even though the SEB’s ‘industrial education’ initiative included black education as one of its stated goals (from schools such as the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and Hampton Institute in Virginia), Alderman very clearly dissociated himself from these activities. In a 1911 letter he wrote that the ‘Negro’ question would be settled by “silence and slow time…and I never discuss it, if I can help it, though I hope I am always working toward its rational solution.”[58] Alderman also felt that the race question could be solved through disenfranchisement, stating in 1911:

The South has never been in so generous and thoughtful a mood toward the Negro race as it is today. While his disfranchisement is going on apace, this is a movement to get rid of the Negro as a menacing political factor, disturbing the judgment of men and arousing their passions in order to get a breathing spell in which to think of him righteously and justly as a human being, as a racial problem, as a black man, who cannot be sent away, and who cannot be permitted to dominate intelligence. Whites having established forever their dominance and integrity as a race, they must justify themselves to posterity by acting toward the Negro in a spirit of justice and wisdom.[59]

!["Dr. Edwin Anderson Alderman of U. of Va. At Wilson memorial service, [12/15/24]" in National Photo Company Collection (LC-F81- 33599 [P&P]), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.](http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/14033/2017/04/26519r-216x300.jpeg)

“Dr. Edwin Anderson Alderman of U. of Va. At Wilson memorial service, [12/15/24]” in National Photo Company Collection (LC-F81- 33599 [P&P]), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Click on image to learn more.

Alderman argued that disenfranchisement was the price blacks needed to pay in exchange for relaxation of racial tensions. Alderman did believe that blacks should receive some form of education, however, it needed to be an inferior education. Alderman’s writings make clear his position on black disenfranchisement and the coding of Jim Crow laws in the New South. Ultimately, he took a passive role in the actual creation of laws and the establishment of an inferior black public school system.[60]

Many questions are left unanswered about Edwin Alderman. While he hoped to persuade the masses to fund his public education system, did he believe all of the masses should be inheritors of this education? Alderman criticized private education that it would eventually lead to “aristocracy in education pure and simple.”[61] But, what remains distinct from the public education Alderman created and the private schools he so despised? Alderman celebrated the creation of the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts established in Raleigh in 1887 (today North Carolina State University) because it allowed UNC to be free from “being embarrassed by the constant demand to build stables and workshops, buy prize cattle and modern machinery.”[62] Did Alderman envision a higher education school system stratified by racial, class, and gender divides? Just as the man he so admired, Thomas Jefferson, Alderman was a man full of ambiguity.

[1] Rachael Long, “Alderman Residence Hall,” in Building Notes (Chapel Hill: Facilities Planning and Design, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1993): 32.

[2] “Meeting of the Committee, February 5, 1936.” Records of the Buildings and Grounds Committee, 1919-2002, Faculty Council, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[3] “Meeting of the Committee, February 5, 1936.” Records of the Buildings and Grounds Committee, 1919-2002, Faculty Council, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[4] “Alderman,” University of North Carolina Housing, February 26, 2017, http://housing.unc.edu/residence-halls/alderman.

[5] Dumas Malone, Edwin A. Alderman: A Biography (New York: Doubleday, Doran, & Company, Inc., 1940): 325.

[6] David Reich, “Edwin Anderson Alderman and the Southerner as American,” (Thesis: University of North Carolina, 1994): 45.

[7] James L. Leloudis, Schooling the New South: Pedagogy, Self, and Society in North Carolina, 1880-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999): 34.

[8] Dumas Malone, Edwin A. Alderman: A Biography (New York: Doubleday, Doran, & Company, Inc., 1940): 15.

[9] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 18.

[10] Sarah Brandes Madry, Well Worth a Shindy: The Architectural and Philosophical History of the Old Well at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (New York: iUniverse Inc., 2004): 50.

[11] Robert D.W. Connor and Clarence Poe, The Life and Speeches of Charles Brantley Aycock (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1912): 22.

[12] Kemp P. Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II: From 1868 to 1912 (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1912): 536.

[13] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 27-29.

[14] “Letter to Aycock.” Edwin Anderson Alderman Papers, 1880-1893, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[15] William Snider, Light on the Hill: A History of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992): 127.

[16] Snider, Light on the Hill, 127-128.

[17] “Edwin A. Alderman to Mary Graves Rees, Charlottesville, Virginia, March 15, 1923.” Mary Graves Rees Papers, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[18] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 30-51.

[19] Leloudis, Schooling the New South, 89.

[20] Leloudis, Schooling the New South, 40-43.

[21] Snider, Light on the Hill, 128.

[22] Leloudis, Schooling the New South, 105-106.

[23] Snider, Light on the Hill, 128-130.

[24] Greensboro Record, June 8, 1893.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Snider, Light on the Hill, 129.

[27] Edwin Alderman, “Campus Library,” UNC Alumni Quarterly, October 1894, 10-14.

[28] Snider, Light on the Hill, 129.

[29] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 58.

[30] Snider, Light on the Hill, 129.

[31] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 51-67.

[32] Leloudis, Schooling the New South, 111.

[33] Madry, Well Worth a Shindy, 66.

[34] Ibid., 67.

[35] Louis Round Wilson, Historical Sketches (Durham: Moore Publishing Company, 1976): 29.

[36] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 63.

[37] Edwin A. Alderman, National Education Association: Journal of Proceedings and Addresses (Winona: The Association, 1907-1915): 981-982.

[38] Edwin A. Alderman, National Education Association: Journal of Proceedings and Addresses (Winona: The Association, 1907-1915): 986.

[39] Snider, Light on the Hill, 130.

[40] Leloudis, Schooling the New South, 45.

[41] Louis Round Wilson, Historical Sketches (Durham: Moore Publishing Company, 1976): 27.

[42] Madry, Well Worth a Shindy, 56.

[43] Madry, Well Worth a Shindy, 60.

[44] “Edwin A. Alderman to Mary Graves Rees, Charlottesville, Virginia, December 16, 1923.” Mary Graves Rees Papers, University Papers, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[45] “Edwin A. Alderman to Mary Graves Rees, Charlottesville, Virginia, December 16, 1923.” Mary Graves Rees Papers, University Papers, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[46] “E.A. Alderman.” Articles on Edwin Anderson Alderman, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[47] Madry, Well Worth a Shindy, 50-53.

[48] Snider, Light on the Hill, 131.

[49] Louis Round Wilson, Historical Sketches, 28-29.

[50] Leloudis, Schooling the New South,134-136.

[51] Snider, Light on the Hill, 139-141.

[52] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 100.

[53] Leloudis, Schooling the New South, 145-146.

[54] John Seiler Brubacher and Willis Rudy, Higher Education in Transition: A History of American Colleges and Universities (Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 1997): 148.

[55] Malone, Edwin A. Alderman, 70-80.

[56] James Becker, “Education and the Southern Aristocracy: The Southern Education Movement, 1881-1913.” Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1972.

[57] Articles on Edwin Anderson Alderman, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[58] Letter, Edwin A. Alderman to Elizabeth Marbury, undated but about 1911, Alderman Papers, University of Virginia.

[59] Edwin A. Alderman, “Education in the South,” Outlook Vol. 68, August 3, 1901.

[60] Dabney, Universal Education, I, 211.

[61] Luther L. Gobbel, Church-State Relationships in Education in North Carolina since 1776 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1938): 166.

[62] Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II, 378.