A Progressive Man and His Modern Building: The Story of Joseph Caldwell and Caldwell Hall

By Noah Janis

“Joseph Caldwell (1773-1835),” in the Portrait Collection (P2), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Carolina prides itself on a number of firsts: the first public university in the nation; the first public university building, Old East, in 1793; the first public university to open its doors in 1795; and the first public university to confer degrees in 1798.[1] The story is oft repeated and transmitted from one generation of Tar Heels to the next, but it is easy to take for granted that our beloved school simply became a major university over time or that it was inevitable. In actuality, UNC faced several crises in its formative years that could have left it with nothing more than a short epitaph in history books. Instead, through the untiring and sacrificial leadership of another Carolina ‘first,’ the university weathered the storms and flourished. Joseph Caldwell, the first official president, worked with the school for most of its first forty years and was progressive in a number of respects: he met the university’s needs, overcame adversity, guided Carolina through early transitions, and was forward-looking in policy. Similarly, his namesake building, Caldwell Hall, was progressive in its modern design and usage with several firsts, in transitions to meet the university and the nation’s needs, and in overcoming challenges with changes and alterations.

From New Jersey to North Carolina

Joseph Caldwell was born on April 21, 1773, in Lamington, New Jersey, to Rachel Harker and Joseph Caldwell.[2] His father and namesake, a physician, died two days before his birth, leaving his widowed mother with three children to raise.[3] He recollected years later that his mother and maternal grandmother “were ever faithful in giving me all the instruction in their power, and especially in training me to the knowledge of God, of the scriptures, to pious sentiment and religious duties.”[4] His family moved several times during his childhood to escape the Revolutionary War swirling around them, but he still received an education at two different schools in Bristol, Pennsylvania, and Princeton, New Jersey.[5] Due to his mother’s limited resources, one of his teachers from the latter institution, Dr. Witherspoon, offered to take in Caldwell so he could continue his studies.[6]

“Joseph Caldwell’s Diploma from the College of New Jersey at Princeton, 1791 (Scan 1),” in the Joseph Caldwell Papers #127, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

At only fourteen, he entered the College of New Jersey at Princeton in 1787 and graduated with a degree four years later.[7] It was here that Caldwell developed a strict moral discipline that he would use to straighten out UNC upon his arrival. Of his college years, he remarked that “if there was any pleasure in the moments of clandestine acts of mischief, it was so mixed in my bosom with the agitations of apprehended discovery, and dread of the consequences darting across my mind, that I should be far from recommending it on the score of enjoyment.”[8] A deeply religious man since his youth, Caldwell studied ministry after college and became a Presbyterian minister in 1796 while also serving as a tutor at his alma mater.[9] Yet his life was about to change dramatically.

Unexpectedly, Caldwell received a letter from an old Princeton acquaintance, Charles Harris, who was a mathematics professor at the newly established University of North Carolina. Harris wanted to enter law and only took the position at UNC for one year, so he offered Caldwell his professorship.[10] With encouragement from his friends, Caldwell agreed and was unanimously approved by the Board of Trustees.[11] He began the long journey to Chapel Hill in September 1796, arriving to find the university consisting of a single two-story building, Old East; two professors, including himself; students “ill-prepared for that quiet devotion to the pursuits of literature and science;” and a local population that was indifferent to education.[12] The obstacles were daunting for the bright young professor and he soon pondered resignation, but the university needed him as a professor and he answered its call by remaining in his position.[13] Thus, Caldwell demonstrated his faithfulness to the institution and his willingness to meet their needs, even if it seemed to be disadvantageous to his career in the short term.

Caldwell as President: Developing Carolina

“List of Subscriptions, July 8, 1809 to January 24, 1811: Page 231,” in the University of North Carolina Papers (#40005), University Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

During his early years as a professor, Caldwell worked with an untiring spirit to straighten out the students and bring respectability to the fledgling school. As a result, he served as the “presiding Officer” of the university for several years in the absence of an official leadership position.[14] He was later elected the first president in 1804.[15] Under his direction, Carolina’s reputation grew in his first few years as president and enrollments increased so much that they began erecting South Building. Yet the General Assembly ceased funding the project and removed other sources of revenue for the university as a whole. South Building was left uncompleted for years, so Caldwell, “whose interest in the Institution was never confined to the faithful discharge of the duties of his peculiar office,” used his entire summer vacation of 1811 to travel around the state soliciting donations.[16] He raised $12,000 in six weeks and even made a substantial contribution himself so that the building was soon completed.[17] Once again faced with adversity, Caldwell invested all his time to aid the university and ensured it could continue accepting more students.

“Campus View: Papercut Illustration, 1814: Scan 1,” in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection Collection #P0004, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

With his fundraising tour complete, Caldwell not only secured the university’s finances but also public support of the fledgling institution. The university had survived its most formative years of turbulence under his care and developed into a prosperous school by 1812. “Having seen it grow up from the humble condition in which he found it to respectability and usefulness,” Caldwell decided to relinquish his position as president in that year and continue his work as professor of mathematics.[18] He then published a geometry textbook that may have been compiled by students from his lectures as early as 1806.[19] His successor as president, Dr. Robert Chapman, retired in 1817 and Caldwell was called back into service as Carolina’s leader for the remainder of his life.[20] Despite efforts by other universities to recruit him, “he clung to our College with a paternal devotion” and once more demonstrated his commitment to meet its need of a stable and trusted leader.[21]

Caldwell as President: Financial Panics and Advancing Science

“Silhouette of UNC President Joseph Caldwell, circa 1815,” in Carolina Keepsakes, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In his second term as university president, Caldwell expanded the curriculum while also pushing for the construction of Old West and Gerrard Hall and the addition of another story to Old East in 1824 due to increased enrollments.[22] The Panic of 1825 hampered these efforts and the university once again found itself in troubled waters. Centered in England before spreading to the United States, the financial collapse began after an investment bubble of Latin American bonds popped, leading to a London stock market crash and bank runs.[23] Funding for the construction projects came from selling donated land in Tennessee, but this could not be done during the recession.[24] Combined with decreasing enrollments from the panic, the university fell into debt over the next few years.[25] The school’s very existence was threatened.

Faced with ruin, Caldwell and the trustees borrowed money and turned to the General Assembly for help in 1830, but it would only do so if given complete control of the institution.[26] The trustees refused and instead borrowed more money to meet the needs of the university as land sales finally increased to repay the debts by 1835.[27] While the financial situation was exacerbated by Caldwell’s construction efforts, it was his and the trustees’ actions to secure loans and sell land that allowed the school to keep its doors open. He managed both to expand the school’s physical presence through building campaigns and to survive an unexpected, worldwide fiscal crisis.

“Observatory and Instruments Purchased by Joseph Caldwell (1773-1885) in Europe,” in Buildings and Grounds (P4.3), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Caldwell was also progressive in his emphasis on advancing science at Carolina. In 1824, he traveled to Europe at the behest of the trustees to purchase books for an expanded library and apparatuses for scientific observation.[28] The trustees entrusted him with $6,000, which he spent with “fidelity and skill.”[29] Yet he also expended an additional $1,738 of his own funds to acquire additional necessary items for the university and was later refunded.[30] Not only did the trustees have faith in his character to travel so far with university funds at his disposal, but he also took it upon himself to further enhance the school’s educational opportunities without knowing whether he would be personally compensated.

Much of the apparatuses purchased in Europe were modern astronomical equipment that Caldwell initially placed in his classroom for observations. With them, he determined “the first approximate values of the latitude and longitude of Chapel Hill.”[31] He then spent $430 of his own money in 1831 to build the first college observatory in the country and was only refunded just before his death.[32] The little building was located on a “low hill just outside the campus” where trees were “cut away so that a sweep of the entire horizon could be made with the altitude and azimuth instrument.”[33] Caldwell and two other professors made observations until his death in 1835, but since he was the driving spirit behind the enterprise, it was soon ignored.[34] The building partially burned in 1838 and the remaining bricks were taken to build a kitchen in 1841.[35] It was not until 1973 that the university built a new observatory located in Morehead Planetarium.[36] Yet for a few years, Caldwell progressively pushed the boundaries of science and astronomy not only at UNC but for all colleges across the nation. By purchasing modern educational materials and equipment, he demonstrated his commitment to developing a strong, advanced university.

Work Beyond Carolina

Joseph Caldwell, The Numbers of Carlton, Addressed to the People of North Carolina, on a Central Rail-Road Through the State. The Rights of Freemen is an Open Trade. (New York: G. Long, 1828), Title Page, accessed on March 25, 2017, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/caldwell/title.html.

Caldwell was also forward-thinking in his opinions on state policy about internal improvements and public education. The former was a hotly contested issue nationwide between the new Democratic and Whig political parties. The term ‘internal improvements’ referred to “canals, turnpikes, railroads and aids to navigation. These devices increased the speed of transportation and cut its costs,” thereby lowering prices and increasing profits.[37] Yet there was a debate over who should pay for the improvements, with Whigs arguing that Congress should support a transportation system and Democrats arguing that it should only pay for navigation aids that benefit the whole country.[38] Caldwell would have sided with the former, although on a smaller scale.

In 1828, Caldwell published his views on internal improvements under the pseudonym “Carlton,” stating that “a railroad, a canal, or a deep and navigable river, reduces almost to nothing the expense of carriage. Any one of these centrally situated, opens a market throughout the state, and with the world.”[39] Yet North Carolina had few navigational aids because of funding problems. Citizens did not want to pay higher taxes for the state to build improvements, but Caldwell argued that in consequence, “the farmer of North-Carolina is labouring under disadvantages in comparison with the farmer of other states.”[40] He championed the construction of a “central rail-road” from New Bern to Raleigh and eventually farther westward that would be funded from its freight revenue, thereby negating the need to raise taxes.[41] For most counties, goods could be brought to the railroad much faster than they could normally be taken to the coast.[42] Caldwell never saw his idea come to fruition, but a central line across the state would be completed almost twenty years later.[43] While his proposal was not immediately successful, it did show that he was progressive in his ideas for developing the state’s economy.

Caldwell arguing the need for primary education, Joseph Caldwell, Letters on Popular Education Addressed to the People of North-Carolina (Hillsborough: Dennis Heartt, 1832), 6. Photo by Noah Janis.

Caldwell was also forward-looking in his views on public education in North Carolina. During his time second term as president, the state had a voluntary system of education without support from the legislature in which a local neighborhood came together, built a schoolhouse, found a schoolmaster, and paid for his salary and maintenance of the building.[44] As with internal improvements, most citizens did not want to raise taxes beyond the bare minimum for maintenance of the government, but other challenges included a widely distributed population that was generally apathetic to public education.[45] Caldwell, who succeeded in rallying state support for UNC through his untiring fundraising campaigns, sought once more to bring North Carolinians behind an education initiative in a series of letters published in 1832.

He devised a detailed plan to create a statewide system of primary schools without raising taxes. His end goal was to “disseminate education through every county of the state, and among every portion of the people.”[46] First, the state should create a “Central School” to train schoolmasters in the “most improved methods of instruction.”[47] Next, the General Assembly should appoint a board of education that will then chose a principal to head the seminary.[48] Each county that wants to participate in the system would appoint school commissioners who select applicants for the seminary to teach in the county.[49] Finally, simple schoolhouses should be built where they are wanted in these counties.[50] The existing state literary fund, with investment, would pay for the buildings, the county would pay for the teacher’s education, and citizens would pay a lawful tuition for their children to support the schoolmaster.[51] Caldwell knew the benefits of primary schooling firsthand and not only sought to progressively transform the state into an educated society but also to do so within the confines of its small government culture. Therefore, through his scientific endeavors at UNC and his economic and educational policies for the state, Caldwell demonstrated that he was a forward-thinking mind for the 1820’s and 1830’s

Joseph Caldwell and Slavery

Monument to November and Wilson Caldwell, “Caldwell Monument, 1890-1939: Scan 2,” in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection Collection #P0004, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Even though Caldwell came from a struggling Northern family, he was still a part of the slave economy in the South. Plantation agriculture spread throughout the South during the antebellum period before the Civil War, and African American enslaved labor was its most dominant feature. This led to growing conflict between slave owners in the region and antislavery northerners.[52] The sources are limited and sparse on details, but Caldwell did own one enslaved person after he moved to North Carolina. His name was November Caldwell and he served as the president’s coachman.[53] He was referred to as Doctor November, either after his master or because students taught him to read and write.[54] Either way, he was well respected and liked by the faculty and students alike, but he was still considered chattel property. Presumably after Caldwell passed away, the university obtained ownership of November, who then worked as a servant. He “ha[d] charge of all the dormitories and recitation rooms” but also earned money from side jobs.[55] His son Wilson served as a janitor at UNC and later as a justice of the peace and town commissioner after emancipation in the Civil War.[56]

Death and Memory

Caldwell suffered from a disease in the last seven years of his life, but the sources are not clear about what it was. He did not discuss it with contemporaries and continued his heavy workload until 1833, when he turned over most of his simultaneous professorship duties to an adjunct. He passed away on January 27, 1835.[57] His death sparked immediate memorializations in a resolution from the Trustees that declared he “has approved himself one of the noblest benefactors of the State and deserves the lasting gratitude and reverence of his countrymen.”[58] Students delivered a eulogy to him at the 1835 commencement and wore “badge[s] of mourning.”[59] At the same time, Walker Anderson wrote and delivered his biography and oration about Caldwell that is a crucial source for much of this paper, although the document’s constant praises and interpretation of his character must be understood in its memorialization context.[60] The General Assembly later named a county after him in 1841.[61] The memory of Caldwell reached its highest point at this time but would soon fade over the next few decades.

Second monument to Joseph Caldwell on McCorkle Place, “Caldwell Monument, 1890-1939: Scan 1,” in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection Collection #P0004, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Memorialization efforts at the university declined within a few years of his death as efforts to name a building after him in 1837 failed.[62] A monument to honor him above his grave was commissioned that same year, but it was poorly built and never completed. Ten years later, fundraising efforts were begun by “older alumni” who “venerated” Caldwell, and President James K. Polk, a UNC graduate, started the subscription effort.[63] Donations were slow in coming and it was not until 1858 that the new marble monument was dedicated.[64] The original sandstone memorial was relocated to the cemetery and eventually altered to honor “three faithful [slaves] of the University,” including November and Wilson Caldwell.[65] Sources are not clear why his legacy changed after the second monument was built, but what is clear is that he and his contributions were mostly forgotten with the Civil War that tore apart the country. By 1911, professor Venable wrote that “little beyond the memory of his name is left where he lived and wrought.”[66] Yet suddenly and unexpectedly, just like his invitation to come to UNC, Caldwell’s name was resurrected the same year of Venable’s comment and placed on a new, modern building that is just as progressive as its namesake.

Origin, Construction, and Dedication of Caldwell Hall

“Caldwell Hall, circa 1911: Scan 1,” in the Collier Cobb Photographic Collection #P0013, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The story of Caldwell Hall begins in late 1910 when Isaac H. Manning, Dean of the Medical School, reported that “the pressing needs of the [Medical] School demand a new building” because its current home was “very inadequate and further changes seem impossible.”[67] In response, the Board of Trustees approved the construction of a new medical laboratory to cost $50,000 and commissioned it Caldwell Hall. The trustees did not state why the name was chosen, but the recommendation for the building and presumably its name came from the “President & Executive Committee of the Faculty.”[68] They did not even specify Caldwell’s first name in the board’s minutes, but the student newspaper the Tar Heel reported that the building was named “in honor of the first president of the University,” who could only be Joseph Caldwell.[69] Nevertheless, construction of the building began almost immediately.

Caldwell Hall was designed by Milburn, Heister, and Company of Washington, D.C., and built by contractor I. G. Lawrence starting in 1911.[70] The Tar Heel stated that it “is being constructed of the white pressed brick of the same kind as has been used in the building Chemistry Hall, the Gym and Davie Hall.”[71] The Alumni Review wrote that “in style of architecture the building approaches the classical Renaissance and consists of a main building and a wing, each of two stories.”[72] It was built simply and with many windows for natural lighting.[73] A visitation committee reported that it was “a modern and handsome building in every respect . . . [and] especially fitted for the purposes for which it was erected.”[74] Yet what were those purposes?

I. G. Lawrence, “Caldwell Hall Cornerstone, 1911” at Caldwell Hall, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Photo by Noah Janis.

As a modern medical laboratory, Caldwell Hall was designed to provide new “histology, pathology, bacteriology, pharmacology, physiology, [and] anatomy” laboratories, lecture rooms, and a library for the School of Medicine. In addition, the building had “comfortable rooms for the care of animals.” Its construction would free up classrooms and dormitories in other buildings, with the school newspaper commenting that “Nothing could have been done which would have relieved the cramped condition of the University in more ways.” Just like the visitation committee, the Tar Heel reported that the Building Committee “spared no pains in their endeavor to make the building complete in every detail and adequate to meet the demands of modern medical education.” The emphasis on “modern” should not be overlooked but rather seen as an indication of its up-to-date medical facilities. Just like its namesake, the building was designed by forward-looking faculty who wanted to provide an advanced scientific education.

Caldwell Hall was dedicated with great fanfare in nearby Gerrard Hall on May 8, 1912. Several honorary degrees were issued and “distinguished” guests spoke about “scientific medicine demands . . . medical education in the Southern States . . . [and] the demands that the [medical] profession makes on the training period of the young physician.”[75] Later that year, the first issue of the Carolina Alumni Review featured a picture of the brand new building on its front cover.[76] The School of Medicine finally had its own modern laboratory and the university was clearly quite proud of the accomplishment.

“Carolina’s Zoo”[77] and the First Rameses Mascots

Among the most talked about aspects of the new Caldwell Hall, and the most controversial, were its animal pens. The creatures were kept in the basement for medical experiments. The Tar Heel reported that “Each student in the Immunology department has one animal which is used as a ‘patient.’ Painless injections and operations are performed [with anesthetics], and the effects noted as part of the work in the course.”[78] By 1927, the basement was referred to as “Carolina’s zoo” and housed many dogs, rabbits, guinea pigs, white rats, sheep, and “an occasional straying cat.”[79] That same year, it was upgraded with electric lights and steam pipes for heat and sterilization, which prompted quips from students that the “zoo” was taking applications for boarders because of a shortage of dorm rooms.[80] Nevertheless, the first known alteration of Caldwell Hall illustrates that the university was dedicated to scientific exploration with lab animals and kept looking forward to provide the best educational opportunities.

“Rameses Dies during Hot Summer Months,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Sep. 29, 1925, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67919582.

Yet the little zoo was not without some major controversy that centered around its most famous guests, the first live Rameses mascots. In 1924, Carolina’s head cheerleader, Vic Huggins, ordered the university’s first mascot for $25. He chose a ram in honor of star football player Jack Merrit, or the ‘Battering Ram,’ and appropriately named the animal ‘Rameses.’ Its first game was a Carolina victory and assuming it was lucky, the university has since always had a live Rameses mascot at football games.[81] After the football and basketball seasons of 1924-1925, Rameses was left in Caldwell Hall for the summer, which prompted disaster.[82]

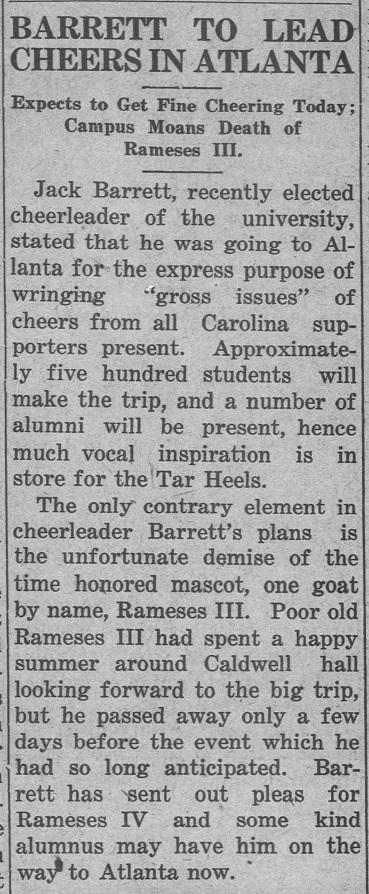

“Barrett to Lead Cheers in Atlanta,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Oct. 11, 1929, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67925096

Shockingly, “when Assistant Cheer Leader Bob Hardee called for him at the beginning of the football season [in 1925], he was informed that the Ram had died,” presumably from heat in the basement.[83] The pedigreed Rameses was supposed to have been placed in Graham Memorial Building but it was not completed in time for the summer, so the animal pens in Caldwell were the only alternative.[84] Thankfully for the cheerleading squad, Rameses had a son who was also housed in Caldwell Hall, presumably because of its animal facilities. Yet in 1926, he also died in the building when medical students extracted his blood. This time, the news received even more coverage in the Tar Heel. It reported with flowery language that Rameses II was survived by his wife and son, saying “there is one remaining consolation, however, and that is, the prince still lives.”[85] Thankfully, the poor rams appear to have been much better cared for after the death of Rameses II, but that did not end the disturbing link between Rameses and Caldwell Hall.

Rameses III has two sons that were born in Caldwell in March 1927.[86] He then passed away in or around the building in the early fall of 1929, but presumably of old age without any mysterious circumstances. Yet unluckily for university athletics, he died a few days before the cheerleaders traveled to Atlanta for a football game against Georgia Tech. The Daily Tar Heel soberly reported that “Poor old Rameses III had spent a happy summer around Caldwell hall looking forward to the big trip.”[87] It is not known when the rams ceased to be kept in the building, but as late as 1933, sheep were pastured behind it and students sarcastically suggested they should be used to cut the tall grass that was left to grow during the Great Depression.[88] While the stories of the rams do not reflect upon the progressiveness of Caldwell Hall, they do demonstrate an interesting point about memory at UNC in that they are left out from descriptions of our mascot’s origin.[89] The building’s brief link to the university’s famous athletic programs has not been found outside of the student newspaper, reflecting an effective silencing of the stories by the school because of their controversial nature.

Transitioning: Carolina’s First Radio Studio and the Naval Pre-Flight School

Phyllis Yates, “Radio Studio to Follow Columbia University Model,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Aug. 4, 1942, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67904007/.

Caldwell Hall faced its first transition in 1939 when the School of Medicine moved into a new building that was ten times larger, making Caldwell “available for greatly needed classroom use.”[90] A building designed as a medical laboratory was suddenly without its intended audience, but it was renovated that same year at the cost of $10,000 to presumably prepare it for its new occupants.[91] On the second floor, a brand new radio studio was added for the first time at Carolina, a luxury that students were pushing for.[92] It could not actually transmit its own programs but rather was wired to other stations that would air its content.[93] The studio opened on January 14, 1940, under student control and faculty supervision.[94]

The intention was to “present an honest as well as complete picture of the activities and purposes of the University.”[95] During its brief tenure, the studio broadcasted concerts, plays from Playmaker’s, educational programs, and even “morale and defense information” during WWII to ”180 mutual stations reaching a million listeners.”[96] Yet despite its success and popularity, the studio was vacated on April 29, 1942, to make room for new occupants, leading unhappy students to say it was “blitzkrieged,” a German term referring to the rapid Nazi invasion of France.[97] Nevertheless, for two years, Caldwell Hall was home to a unique Carolina first, demonstrating that the building was still progressive and forward-looking even when faced with the challenge of losing its designed program.

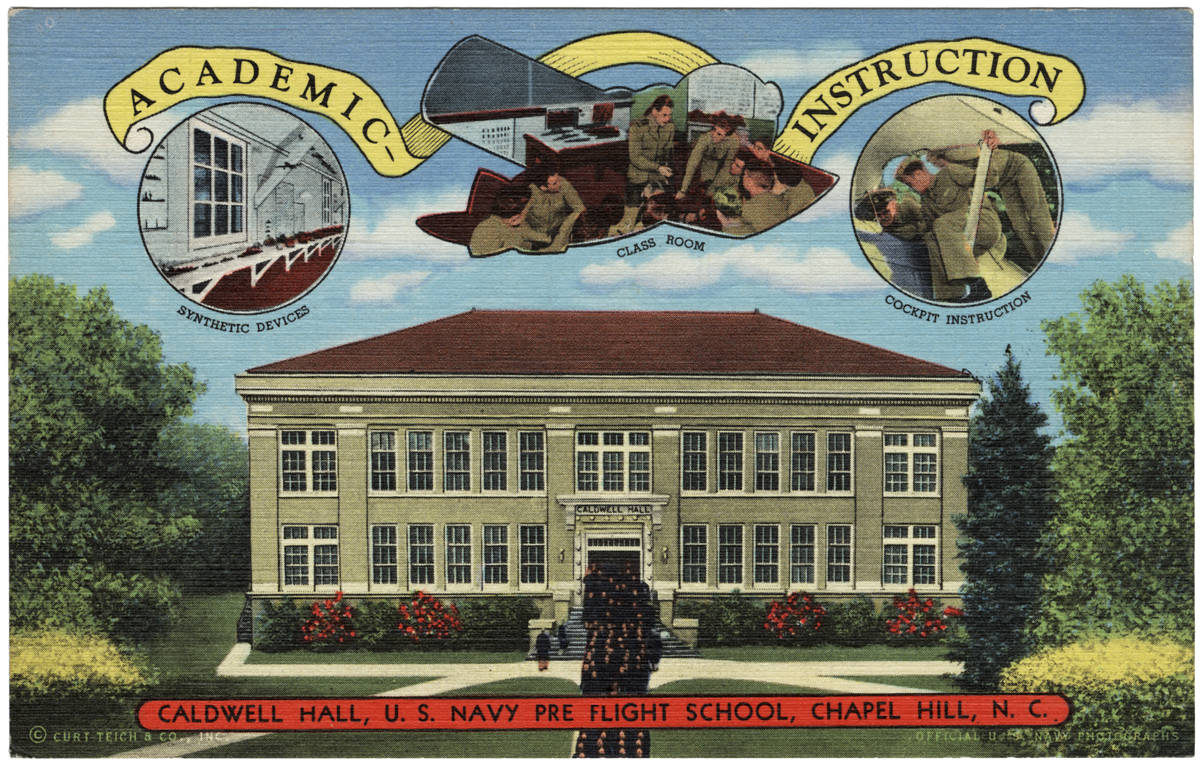

“Caldwell Hall, U.S. Navy Pre Flight School, Chapel Hill, N.C.” in Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The radio studio’s replacement was the United States Navy, which requisitioned Caldwell Hall as the classroom building for the Naval Pre-Flight Training School. UNC was chosen as one of four universities across the country to train naval aviators physically and mentally for combat in WWII.[98] The cadets included students from Carolina’s Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) whom university faculty taught official Navy curriculum. They drilled with weapons on campus and were housed in separate dormitories but also continued as normal students with clubs and activities.[99] In Caldwell, the cadets would learn “seamanship, gunnery, first aid, chemical warfare, strategy, parachute jumping, political drills, mathematics, physics, communications, and general naval lore.”[100] Renovations were conducted in 1942 at the cost of $4,231.35 to prepare the building for its new occupants, which was later refunded by the navy.[101] There is no indication of when exactly the navy ceased using Caldwell, but it was most likely once the war ended in 1945. When the building was needed for war, the university answered the call, showing that it was prepared to meet and transition through unique challenges like its namesake.

Caldwell Hall in Peacetime

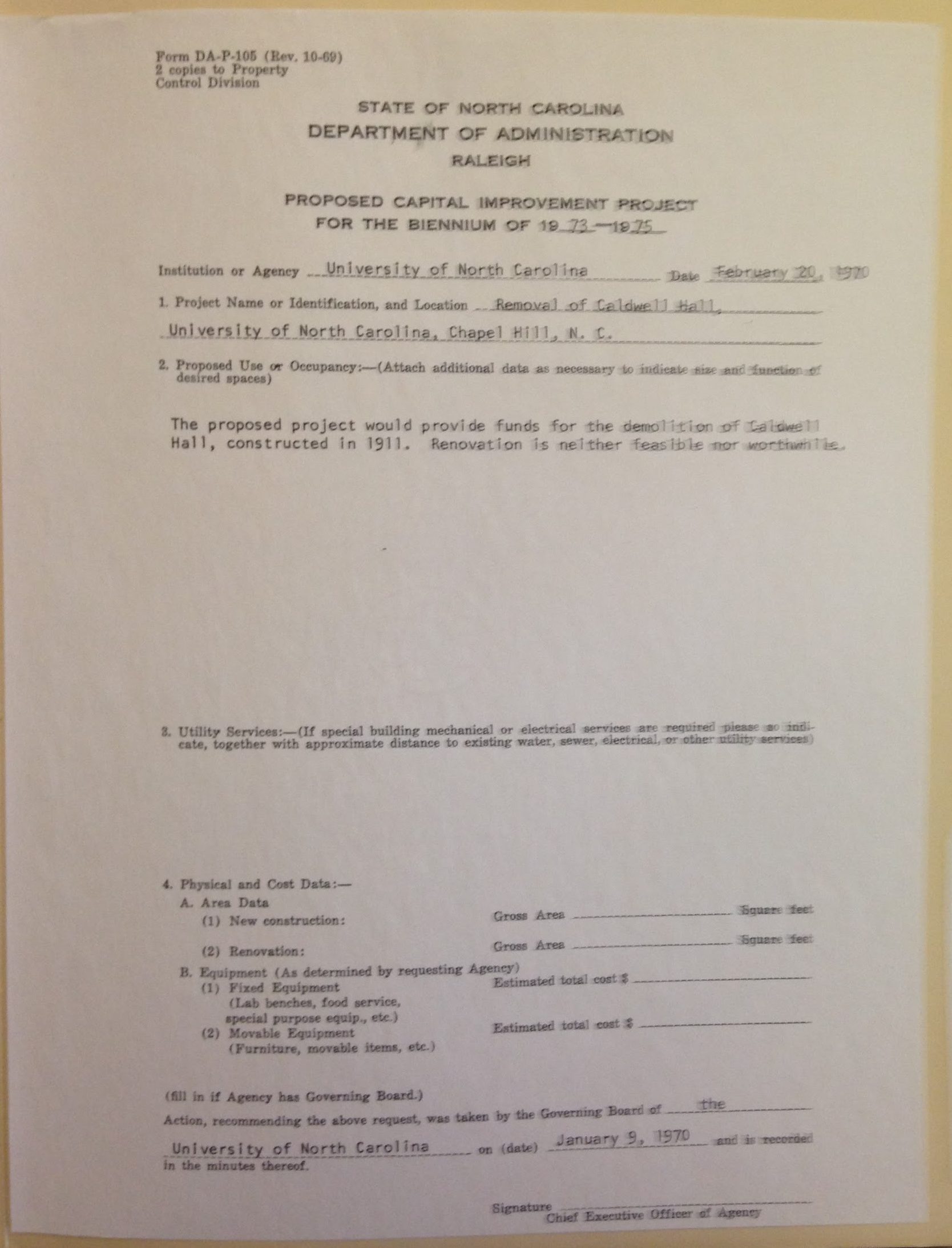

“Proposed Capital Improvement Project for the Biennium of 1973-1975, February 20, 1970,” in Box 2:3:11 of the Facilities Planning and Design Office of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40100, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Photo by Noah Janis.

After the war, Caldwell Hall transitioned into a busy classroom building for students once again, this time housing the philosophy and political science departments.[102] With only one narrow entryway, the university added fire escapes on both sides of the building between November 1953 and June 1955, that, along with stairways for five other buildings, cost over $12,000.[103] In addition to classes, Caldwell featured many philosophy lectures in the postwar years.[104] Yet despite its constant use, the building soon faced its biggest threat.

The building evidently deteriorated rapidly after the navy left, resulting in a proposal to demolish Caldwell Hall because “renovation is neither feasible nor worthwhile.”[105] The project to replace Caldwell proved to be too expensive, however, so the university opted instead to only conduct “essential ceiling and floor repairs” for about $24,500 in 1973.[106] Miraculously, the building not only survived, but thrived as it took on more programs. The rear wing was renovated in 1982 or 1983 at an estimated cost of $29,050 to provide offices for the study abroad and women’s studies programs.[107] Today, Caldwell Hall is home to the philosophy and women’s studies departments and the Parr Center for Ethics.[108] Thus, when faced with its greatest challenge, Caldwell Hall persevered through alterations that transitioned the building into a new era of study.

Memory of Joseph Caldwell and Caldwell Hall in the 20th and 21st Centuries

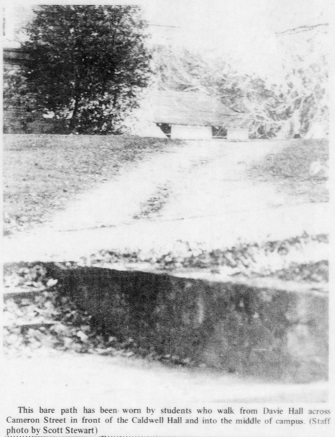

“Convenience and Campus Eyesores,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Nov. 18, 1971, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67805056.

Finally, the memory of Caldwell Hall and Joseph Caldwell has also entered a new era with the coming of a new century. Despite having a building named after him, there is no evidence of a resurgence of study or memorialization of Joseph Caldwell during the twentieth century beyond his inclusion in Battle’s 1907 book History of the University of North Carolina. In contrast, the perception of Caldwell Hall changed around 1970 when it was threatened with demolition. Beforehand, the building was highly utilized by a wide array of occupants. Afterward, it was viewed differently by students who no longer considered it useful or modern, with one writing in the Daily Tar Heel that it should be taken to the Earth Day “Trash-In” and another complaining about its landscaping as being an “eyesore.”[109]

With Caldwell Hall’s small-scale renovations in the 1970’s and 1980’s, student perspectives changed to the point that they wondered why it was so clean and did not have much graffiti like most buildings. One student quipped, “Where are all the amateur philosophers?”[110] Additionally, the twenty-first century has seen a revival in interest of not just the building but the man behind it. The Daily Tar Heel in 2015 identified Caldwell Hall as one of twelve buildings that exhibited institutional racism because of Joseph Caldwell’s owning an enslaved person, November Caldwell.[111] Instead of being seen as modern or progressive, both the building and its namesake are now seen as backward and racist. Only time will tell how their memory might change.

Conclusion and Additional Resources

It was not inevitable that Caldwell Hall would survive, nor was it inevitable that the university would survive under Joseph Caldwell’s leadership. It was only through transitions and luck that the former is still used today, while it took progressive, forward-looking policies and untiring devotion by the president to guide the institution through its formative years. Both the building and its namesake overcame adversity, accomplished a number of firsts, and pushed the boundaries of modern scientific education, all while meeting the needs of the university, state, and/or nation. Yet the story of the two Caldwell’s is certainly not complete because the study of history is open-ended and subject to new interpretations. The narrative presented here is just one of those interpretations out of an endless array of possibilities based on the available sources, which themselves do not offer a complete picture of either Joseph Caldwell or Caldwell Hall.

Modern view of the entrance to Caldwell Hall. “Maps: Caldwell Hall,” The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, accessed March 26, 2017, https://maps.unc.edu/.

I encourage the reader to further investigate the sources utilized here. The Daily Tar Heel archives provide concrete coverage about the building over time and student perceptions of it, especially concerning the Rameses stories, the radio studio, and the Naval Pre-Flight Training School. Caldwell and Anderson’s Autobiography and Biography and Anderson’s Oration on the Life and Character are the only overviews of Joseph Caldwell’s life and, as discussed earlier, the latter was written to celebrate the president after his death. Additionally, the biographical portion of the former is essentially copied from the latter, but Caldwell’s autobiography of his early years is unique. Yet information in both sources about Caldwell’s life and impact at the university are corroborated in Battle’s History of the University, which is a comprehensive secondary source about the school through 1907. It is especially useful for historical context not discussed in Anderson’s work, such as the effect of the Panic of 1825 on the university. It is my hope that further study will be done on and new sources discovered about the fascinating history of Joseph Caldwell and his namesake building.

[1] “FAQs,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed March 25, 2017,

https://museum.unc.edu/faqs.

[2] Walker Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character of the Rev. Jos. Caldwell, D.D. Late President of the University of North Carolina : Delivered at the Request of the Executive Committee, Before the Trustees, the Faculty and the Students in Person Hall, on the 24th of June, 1835 (Raleigh: J. Gales & Son, 1835), 8-9, https://archive.org/details/orationonlifecha00ande.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Joseph Caldwell and Walker Anderson, Autobiography and Biography of Rev. Joseph Caldwell, D.D., L.L.D., First President of the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: J.B. Neathery, 1860), 11, http://www.docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/caldwell/caldwell.html.

[5] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 9-10; Caldwell and Anderson, Autobiography and Biography, 14, 17.

[6] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 14; Caldwell and Anderson, Autobiography and Biography, 25.

[7] Ibid., 28; “Joseph Caldwell’s Diploma from the College of New Jersey at Princeton, 1791 (Scan 1),” in the Joseph Caldwell Papers #127, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[8] Caldwell and Anderson, Autobiography and Biography, 29.

[9] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 21, 27.

[10] Ibid., 25-26.

[11] Ibid., 26-27.

[12] Ibid., 27-28.

[13] Caldwell and Anderson, Autobiography and Biography, 59-60.

[14] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 29.

[15] Ibid., 30.

[16] Ibid., 30-31.

[17] Ibid., 31.

[18] Ibid., 32.

[19] Ibid.; “Volume 2: ‘A New System of Geometry By the Reverend Joseph Caldwell, Professor of Mathematics and President of the University of North Carolina,’ transcribed by Edward McKay, Chapel Hill, N.C., 1806 (Scan 2),” in the Joseph Caldwell Papers #127, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[20] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 33.

[21] Caldwell and Anderson, Autobiography and Biography, 62.

[22] Kemp P. Battle, “History of the University of North Carolina. Volume I: From its Beginning to the Death of President Swain, 1789-1868 (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1907), 255, 280, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/battle1/battle1.html.

[23] Don Morgan and James Narron, “Crisis Chronicles: The Panic of 1825 and the Most Fantastic Financial Swindle of All Time,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York: Liberty Street Economics, April 10, 2015, accessed on March 25, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2015/04/crisis-chronicles-the-panic-of-1825-and-the-most-fantastic-financial-swindle-of-all-time-.html.

[24] Ibid., 282.

[25] Ibid., 325.

[26] Ibid., 325, 328, 333.

[27] Ibid., 334, 402-03.

[28] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 34.

[29] F. P. Venable, “A College President of a Hundred Years Ago,” The University Record 91 (1911): 14, accessed on March 25, 2017, http://library.digitalnc.org/cdm/ref/collection/yearbooks/id/12438; Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 35.

[30] Venable, “A College President,” 14.

[31] James L. Love, “The First College Observatory in the United States,” The Sidereal Messenger 7, no. 10 (1888): 417, accessed on March 25, 2017, https://archive.org/stream/astronomyandast00obsegoog#page/n428/mode/2up.

[32] Ibid., 418; Venable, “A College President,” 14.

[33] Love, “The First College Observatory,” 418.

[34] Ibid., 419.

[35] Ibid.; “Board Minutes: Executive Committee, 1835-1873 (Reel 5): Scan 98,” in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[36] Nancy Woodard, “Caldwell’s Observatory Dream Finally a Reality,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Apr. 26, 1973, accessed on March 25, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67848043/.

[37] Harry L. Watson, Andrew Jackson vs. Henry Clay: Democracy and Development in Antebellum America (Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 1998), 20.

[38] Ibid., 20, 78.

[39] Joseph Caldwell, The Numbers of Carlton, Addressed to the People of North Carolina, on a Central Rail-Road Through the State. The Rights of Freemen is an Open Trade. (New York: G. Long, 1828), 144, accessed on March 25, 2017, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/caldwell/caldwell.html.

[40] Ibid., 4, 152.

[41] Ibid., 164.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Jennifer L. Larson, “Groundbreaking Transportation: 165 Years After the North Carolina Railroad Company’s Beginnings,” Documenting the American South, last modified March 25, 2017, accessed on March 25, 2017, http://docsouth.unc.edu/highlights/railroad.html.

[44] Joseph Caldwell, Letters on Popular Education Addressed to the People of North-Carolina (Hillsborough: Dennis Heartt, 1832), 10.

[45] Ibid., 3-4.

[46] Ibid., 9.

[47] Ibid., 24.

[48] Ibid., 26.

[49] Ibid., 30.

[50] Ibid., 28, 31.

[51] Ibid., 28, 30-31.

[52] Watson, Andrew Jackson vs. Henry Clay, 4.

[53] Battle, History of the University, 601; Edwin Caldwell, Jr., interview by Kathryn Walbert, Southern Oral History Program, in the Southern Historical Collection Manuscripts Department, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, July 6, 1995, 1.

[54] Ibid.; Battle, History of the University, 601.

[55] Ibid.

[56] “Wilson Caldwell,” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, accessed March 26, 2017, https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/segregation/wilson-caldwell.

[57] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 36-7.

[58] Battle, History of the University, 413.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Anderson, Oration on the Life and Character, 3.

[61] Battle, History of the University, 412.

[62] “Board Minutes: Executive Committee, 1835-1873 (Reel 5): Scan 52,” in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[63] Kemp P. Battle, “The Two Caldwell Monuments on the Campus of the University of North Carolina,” University of North Carolina Magazine, December 1902, 106, 108, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://archive.org/details/twocaldwellmonum00batt.

[64]Ibid., 108.

[65] Battle, History of the University, 694-95.

[66] Venable, “A College President,” 15.

[67] “Board Minutes: May 1904-September 1916 (Scan 297),” in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[68] “Board Minutes: May 1904-September 1916 (Scan 309),” in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[69] “Dedication of Caldwell Hall Takes Place,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 9, 1912, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67867813.

[70] I. G. Lawrence, “Caldwell Hall Cornerstone, 1911” at Caldwell Hall, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Daniel J. Vivian, “Milburn, Heister, and Company (1909-1934),” North Carolina Architects & Builders: A Biographical Dictionary, last modified 2009, accessed on March 26, 2017, http://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000011.

[71] “Improvements on Campus,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Oct. 3, 1911, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67867074/.

[72] “The Medical School Finds a Permanent Home,” Carolina Alumni Review 1, no. 1 (1912): 16-17, accessed on March 26, 2017, http://www.carolinaalumnireview.com/carolinaalumnireview/191210?pg=17#pg17.

[73] Ibid., 17.

[74] “Board Minutes: May 1904-September 1916 (Scan 358),” in the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records #40001, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[75] “Dedication of Caldwell Hall Takes Place,” Tar Heel, accessed on March 26, 2017.

[76] “The First Issue of the Alumni Review,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Oct 30, 1912, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67868034.

[77] “Carolina’s Zoo is Modernized,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Nov 3, 1927, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67857965.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid.; “Applications Now in Order,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Nov 8, 1927, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67858016.

[81] “FAQs,” The Carolina Story.

[82] “Rameses Dies during Hot Summer Months,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Sep. 29, 1925, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67919582.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Ibid.

[85] “Rameses II. Of Royal Pedigreed Descent Joins His Predecessor in Eternal Rest,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Mar. 27, 1926, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67919844.

[86] “Ramases Now Has Couple of Sons,” Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Mar. 8, 1927, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67920186

[87] “Barrett to Lead Cheers in Atlanta,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Oct. 11, 1929, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67925096; Carolina won 18-7, see “Carolina Crushes Tech 18 to 7,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Oct. 12, 1929, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67925102/.

[88] R. L. B., “The Grass Grows Taller Every Day,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 7, 1933, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67918097/.

[89] “FAQs,” The Carolina Story.

[90] “New Quarters of Class A University Medical School,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 28, 1939, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67844673; “Growth of Physical Plant of University from Old East to Newest Buildings is Told,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 28, 1939, accessed on March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67851309/.

[91] “Largest Number of Projects in Progress Here,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Jan. 15, 1939, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67848427.

[92] “Radio Studio Begins Operation December 1 in Caldwell Hall; Contracts to be Granted Soon,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Oct. 5, 1939, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67844297/.

[93] “Radio Studio Staff Plans to Air Live, Vital Programs,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Jan. 12, 1940, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67847016.

[94] “Campus Studio Goes on Air Today,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Jan. 14, 1940, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67847091/; “Earl Wynn Tells Frosh of Studio,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Jan. 12, 1940, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67847595.

[95] Ibid.

[96] “Campus Radio Studio Keeps State Informed,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 10, 1942, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67903627; “Director Wynn Responsible for Radio Studio’s Success,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Jan. 31, 1942, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67901005.

[97] “Radio Studios Quit Yesterday; Navy Starts Moving In,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Apr. 30, 1942, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67903321.

[98] “Carolina Will Toughen Future Pilots for Navy,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), May 10, 1942, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67903604.

[99] Janis Holder, “Training Programs,” A Nursery of Patriotism: The University at War, 1861-1945, accessed April 22, 2017, https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/patriotism/wwii/training.

[100] “Carolina Will Toughen Future Pilots for Navy,” Daily Tar Heel, accessed March 26, 2017.

[101] “Monthly Report on Permanent Improvement: Appropriation and Allotments, Month of January 1942,” in Volume 81 of the Records of the Accounting Department #40097, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; “Receipts Register A/c Classification, Month of June 1946,” in Volume 81 of the Records of the Accounting Department #40097, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[102] “Campus Keyboard,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Jan. 7, 1947, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67925688.

[103] Ibid.; “Monthly Report on Permanent Improvements: Appropriation and Allotments, Month of November 1953,” in Volume 52 of the Records of the Accounting Department #40097, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; “Monthly Report on Permanent Improvements: Appropriation and Allotments, Month of June 1955,” in Volume 52 of the Records of the Accounting Department #40097, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[104] “Today’s Events: Symposium Slate,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Mar. 20, 1958, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67787297.

[105] “Proposed Capital Improvement Project for the Biennium of 1973-1975, February 20, 1970,” in Box 2:3:11 of the Facilities Planning and Design Office of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40100, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[106] “Capital Improvement Allotment 1858,” in Box 2:3:11 of the Facilities Planning and Design Office of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40100, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[107] “S. Thomas Shumate, Jr., to Mr. Mike Parker, July 9, 1982,” in Box 2:3:11 of the Facilities Planning and Design Office of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40100, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; “Mike Parker to Mr. Thomas Shumate, December 1, 1982,” in Box 2:3:11 of the Facilities Planning and Design Office of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40100, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[108] “UNC Map,” UNC Chapel Hill Housing and Residential Education, accessed April 22, 2017, http://housing.unc.edu/sites/housing.unc.edu/files/UNC_Map.pdf; “Contast Us,” The Parr Center for Ethics, accessed April 22, 2017, http://parrcenter.unc.edu/about/contact/.

[109] Robert Trudeau, “Grad Students Needed Help to Contribute to ‘Trash-In’,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Apr. 24, 1970, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67789875; Ellen Gilliam, “Convenience and Campus Eyesores,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Nov. 18, 1971, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67805056.

[110] Karen Fisher and Mike Truell, “Graffiti Reflects Many Attitudes,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Oct. 21, 1982, accessed March 26, 2017, https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67845628.

[111] Daniel Lockwood, “Evidence of Institutional Racism at UNC,” Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, NC), Feb. 20, 2015, accessed March 26, 2017, http://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2015/02/evidence-of-institutional-racism-at-unc.