Portrait of George Moses Horton (via Black Then)

Of all of the buildings standing at the University of North Carolina, only five are named after African Americans, and only one of those buildings is named after a formerly enslaved person: Horton Residence Hall.[1] The residence hall, built in 2002 and renamed in 2006, is named after George Moses Horton, a former slave and poet from Chatham County, North Carolina. For most of his adult life leading up to the Civil War, Horton traveled eight miles to UNC each Sunday from his home in Chatham County to sell produce at market and to perform oral poems for UNC students. Horton tried, on several occasions, to purchase his emancipation, and also asked for the aid of University officials, including University presidents Joseph Caldwell and David Lowry Swain, to no avail. UNC boasts that they are reportedly the first center of higher education with a building named after a formerly enslaved person.

“Bewailing mid the ruthless wave

I lift my feeble hand to thee

Let me no longer be a slave,

But drop the fetters and be free.

Why will regardless Fortune sleep

Deaf to my penitential prayer

Or leave the struggling bard to weep

Alas, and languish in despair?

He is an eagle void of wings,

Aspiring to the mountain’s height,

Yet in the vale aloud he sings

For pity’s aid to give him flight.

Then listen all who never felt

For fettered genius heretofore,

Let hearts of petrification melt,

And bid the gifted Negro soar.”[2]

— “Poet’s Petition,” George Moses Horton

George Moses Horton: Early Life

Richard Walser’s account of the life of George Moses Horton’s life begins: “Time, flowing past on its eagle’s wings, does not feel compelled to account for a man’s birth. It drops him where it will.”[3] Much like the history of many other enslaved people — Horton’s official date of birth is unknown, but it is estimated that he was born in 1798.[4] Horton himself once admitted, “To account for my age is beyond the reach of my power.”[5]

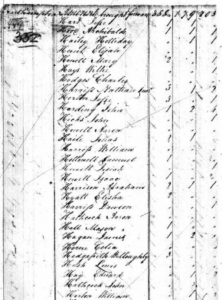

Horton was born into the possession of a white man named William Horton, from whom George gained his surname. William Horton also owned George’s mother and five older sisters at the time of George’s birth, and later owned George’s four younger siblings as well.[6] Although George’s father isn’t named, it is likely that he lived with the family, as the 1800 United States Census lists William Horton as owning eight slaves.[7]

1800 United States Census record for William Horton (bottom row) (via Ancestry.com)

The Horton family and their slaves initially resided in Northampton County, North Carolina, on property consisting of “vast tobacco acres [that] required the busy hands of field labor.” But after several years of hard labor and overuse of the land, the Horton property became “sterile.” Because of this, George stated that around 1800, “my old master assumed the notion to move to Chatham, a more fertile and fresh part of country recently settled and whose waters were far more healthy and agreeable.”.[8]

The plot of land purchased by William Horton was about nine miles from the county seat of Pittsboro and about eight miles from the University of North Carolina.[9] According to The Rocky Mount Telegram, “Young George” served on the new farm as a “cowboy,” working as a field hand who drove the cows to and from the pasture.[10] “In the course of this disagreeable occupation,” he stated, “I became frond of hearing people read; but being nothing but a poor cow-boy, I had but little or no thought of ever being able to read or spell one word or sentence in any book whatever.”[11]

As a child, George loved music, and often paced his “cowboy” movements to the hymns he heard in church.[12] He also had had a strong attraction to the books he saw white school children carrying, and, though his mother recognized this interest in her son, she had no means to support his endeavors as an enslaved woman. So George committed to learning the alphabet on his own, asking white schoolchildren for assistance in his memorization, and acquiring some of their spelling books after the children finished using them.[13]

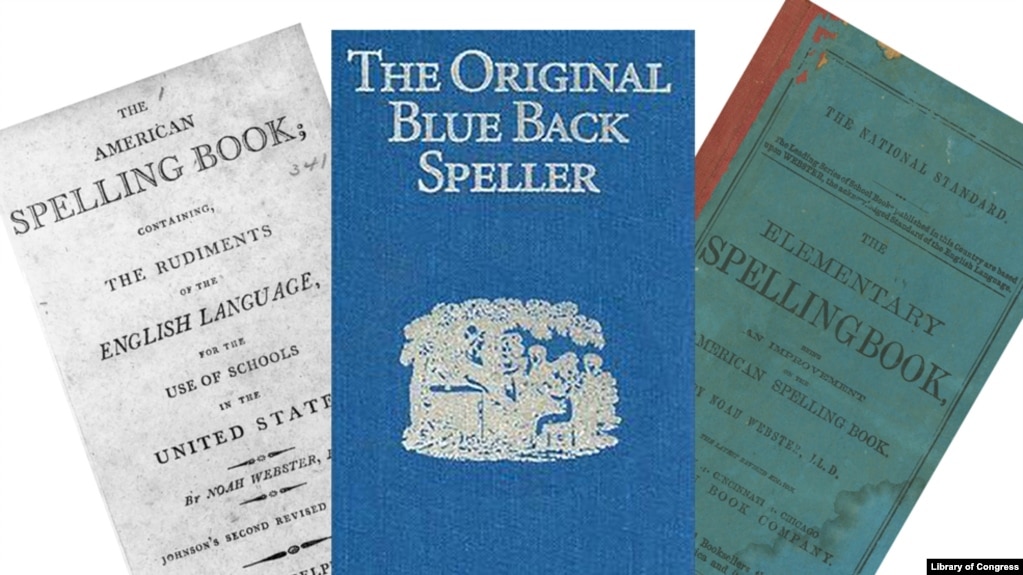

The book that taught Horton to read (via Learning English)

For the next several years, George spent every Sabbath — during his only free time of the week — and nearly every evening sitting in the shade of a tree at the edge of the property, teaching himself to read. It was a laborious task, one that often left him stressed and sweating. Many tried to discourage him — from his mother, to his peers, to his younger brother, who rivaled him in his literary aspiration. But he continued on, stating, “Nevertheless did I persevere with an indefatigable resolution, at the risk of success.”[14]

According to a 1974 article in the Daily Tar Heel, after the “blueback speller” he memorized, George “progressed to a Bible and his mother’s Methodist hymnal. The rhythm and flow of the words somehow struck a chord inside him; soon he found himself making rhymes in his head as he plowed the fields or chopped wood.”[15] Although he could barely read and still could not write, George was already a poet as a teenager. One of the first poems attributed to George Moses Horton was written around this time, which reads:

“Rise up, my soul, and let us go

Up to the gospel feast;

Gird on the garment white as snow,

To join and be a guest.

Dost thou not hear the trumpet call

For thee, my soul, for thee?

Not only thee, my soul, but all

May rise up and enter free.”[16]

At the same time as George was acquiring language with which he could recite rhymes, his owner, William Horton, increased his land holdings in Chatham County fourfold by 1806. The Horton family primarily farmed corn and wheat, as tobacco and cotton exhausted the land too quickly, and weren’t profitable, as the markets were too far away from their property.[17]

But, because of this growing land and labor, George was called upon more and more to perform tasks around the farm. He had less time to study from his books. But he still found time to recite poetry in his head, even as he performed menial tasks.[18]

By 1815, William Horton was nearly seventy-seven, and thinking about the end of his own life. Rather than waiting for his slaves to be given to his children in his will after he died, William decided to distribute some of his property, while he was still alive, to his children.[19] George recounts the feeling of such a day in his poem, “Division of An Estate,” wherein he states, “The day of separation is at hand; / … On which we soon must stand with hopeful smiles, / Or apprehending frowns; to tumble on.”[20] According to the Rocky Mount Telegram, “Lots were drawn and [William’s] son James Horton,” who also lived in Chatham County at this point in time, “fell heir to George.”[21]

In the possession of James, “[w]hippings seemed to have been comparatively rare”[22] and slaves had the ability to travel on their own — to go fishing, to go to church, and to venture to other towns. It was here where George first gained the ability to travel to the University of North Carolina.[23]

“The Black Bard” at The University of North Carolina

The Franklin Street that George Moses Horton came upon during his 19th century visits (via The University of North Carolina)

In 1817, George Moses Horton first began to make his pilgrimages to Chapel Hill, home of the University of North Carolina.[24] One of George’s new responsibilities under the possession of James Horton was to carry fruit to market in Chapel Hill every Sunday.[25] George did not complain, because he was enjoying his new freedoms, and he also “heard that the young students cared for poetry as did he, and he was secretly eager to form their acquaintance.”[26]

The Chapel Hill that George first visited was just “a quarter of a century old,” and still small, covered in forest, and “unimpressive.” In 1817, the student body totaled just over one hundred students, and the students — all white men — spent more time fooling around and socializing than in class or studying. Joseph Caldwell was the University President at the time, and he sought to oversee a University that prided itself on oratory skills and public speeches.[27]

When George first arrived at the University, the students first tried to prank him. In his autobiography, Horton remembered that, “the collegians who, for their diversion, were fond of pranking with the country servants who resorted there for the same purpose that I did, began also to prank with me.” But then, either through conversation or through provocation, the students learned that George had an elevated vocabulary and a knack for rhyme. They insisted that he “spout,” or public speak for them, and George — too long suppressed and ignored — happily obliged. But George was no orator, and quickly embarrassed himself. Instead of turning and hiding, he changed the subject, and brought up poetry, on which he felt he was an expert.[28]

Legend has it that James K. Polk, UNC class of 1818 and eventual President of the United States, was among the first people to encourage George to pursue the poetic tradition.[29] Likewise, much of what is recorded about the life of George Moses Horton is based on legend or secondary sources, with some remaining primary source material. Much of the primary source material left behind by George himself is poetry, through which readers and historians can infer meaning related back to his life; but there is no full or coherent biography encompassing the poet’s life.

Acrostic Poems, taken down by a student at UNC (via the North Carolina State Archives)

George started by by creating acrostics: poems in which the first letter of every line corresponds to a letter in a person’s name.[30] According to a biographical account in a 1974 edition of The Daily Tar Heel, “[B]y the 1820’s he was writing poems on order — chiefly sentimental love ballads which students usually mailed to girlfriends as original compositions.”[31] But George still didn’t know how to write, so George would orate and the students would take down his words in their own handwriting. Many wouldn’t attribute the writing to George, making it difficult to track down all of his writings. Even worse, “[s]ometimes students, seeking self-glorification, signed their names and ‘contributed them’” to Carolina Magazine, an early literary magazine at UNC.[32] New George Moses Horton poems are still being discovered, as they are disparately spread across the country (or even the world). One was just recently discovered in the New York Public Library by Jonathan Senchyne.[33] Thus, many of George’s poems, writings, and musings exist across dozens of family papers throughout the Southern Historical Collection and elsewhere.

Sundays became an exciting time in Chapel Hill, and just as Horton looked forward to and prepared for his eight-mile journey to UNC each week, the students were just as eager for his arrival as well. The students brought him gifts of books, and he brought them gifts of produce and poems. Horton began to charge twenty-five cents per poem, “but some gentlemen, extremely generous, have given [him] from fifty to seventy-five cents, besides many decent and respectable suits of clothes, professing that they would not suffer [him] to pass otherwise and write for them.”[34] This was a fortune for an enslaved man; he made “about $3 to $4 a week, at a time when meat cost 5 cents a pound and eggs were 10 cents a dozen.”[35]

Horton not only had a relationship with students, but also formed a relationship with both President Caldwell and Caroline Lee Hentz, the wife of a professor. Hentz, a poet herself, took interest in Horton, helping him to “transcribe stanzas which he would dictate with quite an air of inspiration.” She would go through and edit his errors in grammar and political correctness as he spoke, helping him to better understand language. She even helped him submit two of his poems to the Lancaster Gazette, where he was first published on April 8, 1828.[36] Horton returned the favor by “writing a touching eulogy when Mrs. Hentz first child died.”[37]

During his year’s worth of Sundays spent in Chapel Hill, Horton tried on several occasions to free himself from enslavement. The first effort was performed by the Manumission Society, who attempted to purchase him from owner James Horton, but to no avail.[38] The Manumission Society of North Carolina was an organization based largely out of Guilford County that sponsored “the emancipation of slaves and emigration of free blacks to Haiti, sponsored by a branch of North Carolina Quakers.”[39] According to a 1974 article in The Evening Telegram that cited Richard Walser’s research, “University President Joseph Caldwell tried [to emancipate him]. Faculty members and their wives spoke in his behalf. Raleigh newspaper editors Joseph and Weston Gales tried. And ‘anonymous philanthropic gentleman’ tried. Governor John Owen offered to purchase the black man’s freedom.”[40]

Freedom’s Journal in New York, an antislavery publication, even spearheaded a campaign to fundraise for the freedom of George, stating, “Something must be done. George M. Horton must be liberated from a state of bondage.”[41] But it was “[a]ll to no avail… The slave owner refused to sell.[42] Shortly thereafter, George wrote “The Slave’s Complaint:”

“Am I sadly cast aside

On misfortune’s rugged tide?

Will the world my pains deride

Forever?

Must I dwell in Slavery’s night

And all pleasure take its flight

Far beyond my feeble sight

Forever?[43]

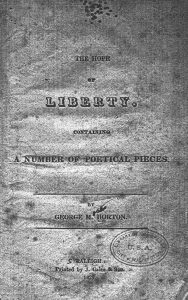

Title page for “The Hope of Liberty” by George Moses Horton (via Documenting the American South)

After publishing a few poems in newspapers in Raleigh and Boston, Horton reached out to publisher Weston R. Gales, of J. Gales & Son, and asked the publisher to consider publishing some of his works. After hearing a testimony from Horton about his previous success with students at UNC, and his desire to use the profits from the sales of his book to liberate himself and sail to Liberia, Gales supported “the plan here urged in his behalf.”[44] Together, Horton and Gales turned the pains of living within “this lowest possible condition of human nature” into a book of poems, entitled The Hope of Liberty, published in 1829.[45] In publishing this book, Horton became “the first black professional writer in America,” the first black author published in the South, and “one of the first professional writers of any race in the South.”[46]

UNC president Joseph Caldwell passed away in 1835 and was replaced by David Lowry Swain in the same year. Unlike Caldwell, Swain didn’t encourage Horton’s studies, as “Swain shared the feelings of the average Southerner that to encourage Negroes in any endeavor outside their ordinary duties was contrary to the best interests of the South.”[47] Horton petitioned Swain on multiple occasions to purchase his freedom, stating that he was “very anxious for some Gentleman in this place to buy [him],” and Swain ignored every request time and time again.[48] Just nine years later, Horton’s master, James Horton, passed away. Neither of these transitions resulted in his manumission, and George Moses Horton passed to Hall Horton, a tanner in Chatham county.[49]

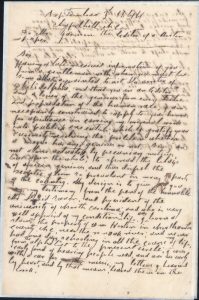

Letter from Horton to David Lowry Swain (via the Slavery and the Making of the University collection)

Hall Horton was adamant: “If his ‘property’ was valuable enough for respectable person to raise money for it, he had no intention of letting it go.”[50] He even referred to Horton as a “worthless nigger” whose “poetry had ruined [him] as a field hand.” In return, Horton, “taking advantage of his earlier experience at Chapel Hill, offered to pay his master 50 cents a day for his freedom if Hall would allow him to move to the University.” Since 50 cents could hire two field hands a day, as opposed to the single man’s labor Horton provided, Hall obliged.[51]

Horton thus spent the next twenty years at the University of North Carolina, continuing to earn a small profit off of his poems and his three books: The Hope of Liberty, Poems by a Slave (1837), and The Poetical Works of George M. Horton (1845). Though President Swain never supported Horton financially or personally, he invited the poet to speak at commencement ceremonies in the 1850s, in front of over 460 students and their families. His speech was entitled, “The Stream of Liberty and Science: An Address to the Collegiates of the University of North Carolina, by George M. Horton, the Black Bard.”[52] The twenty-nine page persuasive speech was likely given in Gerrard Hall, where guests were often invited to speak, and focus on the topic of “the streams of liberty and science [that] flow freely for every man.” But, because it was written in blue ink on parchment paper, and edited several times by several hands, much of the document is now illegible.[53]

This was one of Horton’s last appearances at the University of North Carolina, as the Civil War and Emancipation sent shockwaves through the country — and in the life of George Moses Horton. In 1861, and shut the University down in the years thereafter. Horton was finally free, and his life was no longer bound to the eight mile stretch between UNC and his plantation.[54]

From North Carolina to Pennsylvania

1860s Philadelphia (via the Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

“I feel myself in need

Of the inspiring strains of ancient lore,

My heart to lift, my empty mind to feed,

And all the world explore.”[55]

Upon being liberated, Horton sought to get as far away from ex-master Hall and the rest of his enslaved past as possible. But to do so, he needed sponsorship. He found such support in Will H.S. Banks, a captain of the 9th Michigan Cavalry Volunteers, who took in the poet and helped plan out a future for him. In allowing the ex-slave to travel with him and his Cavalry throughout North Carolina, Banks helped Horton publish a book about his life as formerly enslaved person, entitled Naked Genius.[56] The introduction of Naked Genius read, “This work will be offered to the public as one of the many proofs that God in his infinite wisdom and mercy created the black man for a higher purpose than to toil his life away under the galling yoke of slavery.”[57]

Upon publication, Banks determined his job was done, and said he was returning to Michigan.[58] But first he promised to take Horton northward.[59] Horton realized the time had come for him to leave University and the state he had called home for so long, stating, “With tears I leave these Academic bowers… and take my exit with a breast of pain.”[60]

Horton arrived in Philadelphia in 1866, at a time where there was already a community of about twenty thousand African American people.[61] With a newly published book and a growing circle of admirers in Philadelphia, Horton became something of a celebrity in a short period of time. As Horton himself described such a position, “I reached the threatening heights of literature, and braved in a manner the clouds of disgust which reared in thunders under my feet.”[62]

According to a 1966 article in The Daily Tar Heel, “On Aug. 21, 1866, a special meeting of the Banneker Institute of Pennsylvania was held, ‘the object being to receive Mr. George Horton of North Carolina, a poet of considerable genius.’”[63] However, this was Horton’s first and last time being invited to the Banneker Institute. Horton had a difficult time getting along with the African American community in Philadelphia, as he “felt no conviviality, no comradeship, when he was with those of his own race.” Even more, prose — not poetry — was the medium of the North, and with sub-par writing skills, Horton struggled to keep up.[64]

In 1883, Professor Collier Cobb, a professor of geology from UNC, visited Horton while in Philadelphia on a family trip. During their interaction, Cobb called Horton a “poet,” to which Horton responded, “That pleases me greatly, Professor Cobb… you are using my proper title…” Those were his last recorded words.[65]

George Moses Horton died in 1883, the location unknown, but likely in Philadelphia.[66] According to a biographical article in The Evening Telegram in April of 1974, “his life ended as hopelessly as it had hopefully begun, and it reads like a movie script: he went north, he sought friends, encouragement help… That was Moses Horton: talented, exemplary, unrealized, symbolic and black.”[67]

Memorialization of the “Illiterate Genius”

In Literature

The Black Poet by Richard Walser (via Amazon)

Although George Moses Horton did much work to create a literary footprint in his lifetime, there wasn’t any secondary literature published on his life until over 30 years after his death, at the turn of the 20th century. The first text came from Collier Cobb, the man who visited Horton in Philadelphia just before his death. In 1909, Cobb wrote a ten-page feature on Horton in The University Magazine, entitled, “An American Man of Letters.” Cobb provided a brief biography, highlighted some of Horton’s poetry, and described the man as being “Othello-like.”[68]

In 1917, author Benjamin Brawley highlighted the life and the achievements of Horton in the context of his “faults and even severe limitations” as an enslaved poet.[69] In 1931, Vernon Loggins harshly critiqued Horton’s work as being “primitive,” and in 1939, J. Saunders Redding described Horton’s poetry as being nothing more than “the forerunner of the minstrel poets.”[70]

In 1966, Richard Walser published The Black Poet, a text that helped inform much of Horton’s biography that can be read above. To produce this book, Walser primarily conferred with J.G. de Roulhac Hamilton, the Southern Historical Collection, and Horton’s autobiographical Life of George M. Horton, the Colored Bard of North Carolina. He also referred to dozens of newspaper articles, obituaries, and Horton’s original poems. This text serves as the only book-length biography about Horton, and even includes his own words and autobiographical accounts of his own life.[71]

Don Tate posing with his children’s book (via Don Tate’s Website)

Professor Joan R. Sherman, at Rutgers University, followed Walser’s book with her own critical historical research on Horton. In her book Invisible Poets, she dedicates a chapter to his “poetic strengths,” and in her 1997 book, The Black Bard of North Carolina: George Moses Horton and His Poetry — which also did much work to inform the above biography — Sherman interprets Horton’s poetry, provides biographical context, and critiques the works of the poet.[72]

In 2015, Don Tate published a children’s book about Horton, entitled, “Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton.” The book, recommended for children ages 6 to 10, provides a biography of Horton, colorful imagery, and excerpts of his poems in a child-friendly format.[73]

In Honor

In 1980, the Black Student Movement at UNC, in conjunction with Student Government, held George Moses Horton Day celebrations. The program included an exhibit in the Union, as well as “readings from Horton’s poetry, a biographical sketch, and a scene from a play about him.”[74]

In 1991, the University named an award in the annual pool of Chancellor’s Awards after George Moses Horton. According to the University, The George Moses Horton Award for Multicultural Leadership “honors a nineteenth century poet and friend of students and faculty on this campus.” The University claims that, “[h]is freedom from slavery was purchased in part by funds generated through his popular verse,” but, as stated above, this is not true; Horton was never freed from enslavement on his own accord or the accord of the University, but rather by means of nationwide Emancipation. The George Moses Horton Award “recognizes the senior who has demonstrated outstanding leadership, initiative, and creativity in multicultural education programs.” The award was first introduced when the Sonja Haynes Stone Black Cultural Center was first opened.[75]

In 2006, the Black Student Movement also created a leadership award named after Horton: the George Moses Horton Cultural Performance Award. According to the Umoja Awards website, “This award recognizes a student that has shown similar excellence in the arts as Horton.”[76]

In Building

Horton Residence Hall (via WikiMedia)

Between 2001 and 2011, the University of North Carolina entered a ten-year time period that historians David R. Godschalk and Jonathan B. Howes called “The Dynamic Decade.” In these ten years, UNC made great shifts in the look and feel of its campus, through the creation of buildings, the redesign of structures, and the renaming of various halls.[77]

South Campus, where many undergraduate students lived in residence halls, was a major focus of this shift, as the buildings that existed there prior to 2001 “symbolized the problems inherited from previous eras of urban design on Southeast Campus.” In response, the University erected four new four-story residence halls that added approximately 1600 new beds for undergraduate students.[78]

One such building, completed and opened in 2002, was originally named Hinton James North, because of its proximity to the original Hinton James dormitory.[79] The name Hinton James North was always intended as a temporary name for the dorm until the University could find a suitable replacement name.[80]

The University found that replacement name in 2006, when they announced they were to rename the building to Horton Residence Hall, after George Moses Horton.[81] The name “George Moses Horton Residence Hall” was recommended by Provost Richard Richardson, the chairman of a committee on naming university buildings, and supported by a vote of the Board of Trustees. Richardson discovered Horton while “doing research for the university’s bicentennial celebration.”[82]

“For a man of such enormous deprivation to come out of that and to establish himself as really an intellectual in the community, and to interact with the university so closely, is really an amazing story,” Richardson said. “It added depth and a face and a personality to the whole notion of slavery that I thought needed to be recognized.”[83]

George Moses Horton Residence Hall entrance (via Black and Blue Tour Website)

As the University possessed original copies of some of Horton’s poetry in the Southern Historical Collection, Richardson said he hoped to hang framed copies of those poems in the lobby of the residence hall. It is unclear if the university ever followed through with this plan.[84]

In 2007, at the dedication of the building, Chancellor James Moeser announced that it was likely the first university building in the country to be named after an enslaved person. He stated, “As scholars, educators and students we are responsible, more so than others, for remembering and honoring the past, in all of its complexities and dark moments. It is important for us to do so, not just for our generation, but also for the generations who will follow us.”[85]

The University has since used Horton Residence Hall as an example of its diversity within its annual diversity reports.[86]

In 2006, the publication the Independent Weekly recognized the progress of the University, but highlighted that it still had a long way to go, stating that Horton Residence Hall was “only the fifth of the university’s nearly 250 current structures to be named after an African American and the first named after a slave.”[87] The other four buildings are Blyden and Roberta Jackson Hall, the Tate-Turner-Kuralt Building, Kenon Cheek/Rebecca Clark Building, and the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black History and Culture.[88]

Much of the material regarding the construction and naming of Horton Residence Hall is not yet in the University Archives in Wilson Library, despite fifteen years passing since construction and a decade passing since the renaming of the building. Manuscripts Research and Instruction Librarian Matt Turi states this often happens with more recent documents because the University doesn’t put documents into the University Archives until they are no longer actively in use, or, in historical terms, until they shift from being objects of the present to artifacts of the past.[89]

In Monument

When Yonni Chapman was writing his master’s dissertation in 2006, entitled “Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1973-1960,” he noted that “[d]espite Horton’s accomplishments, brief mentions in the most recent officially sponsored

histories of the university give no indication of the poet’s historical significance.” Chapman envisioned the erection of a monument of Horton in front of Davis Library to honor the late poet and his legacy as a black man at the University.[90] The monument was never produced.

Conclusion

The naming of a residence hall after George Moses Horton is but a step in the right direction for The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Though the naming suggests an acknowledgement of the enslaved past at the University, UNC has not yet acknowledged its prior ownership of enslaved people. Further, in including Horton Residence Hall as a source of pride of diversity within admissions pamphlets and speeches, the University creates a false narrative that they were always sympathetic to the circumstances of enslaved people, and more specifically Horton, when the historic narrative suggests that many University officials actively opposed his emancipation. With dozens of buildings on UNC’s campus named after white persons — and many of the namesakes possessing white supremacist or antiblack personal histories — the existence of the names of merely five African Americans is nearly negligible in the grander scheme of campus naming at the University. George Moses Horton was an incredibly talented, yet socially restricted individual, who played a great role in Chapel Hill social and educational life of the 19th century, and who is rightfully honored by the University; however, in a time in which the named campus landscape is being contested, the University should look towards people who played similar roles as Horton, many of whom were equally ignored or limited by the University in the past.

Works Cited

[1] Jamie Schuman. “UNC to rename dorm for slave.” The Herald-Sun (Durham, N.C.), March 30, 2006.

[2] Martha McMakin. “N.C.’s First Negro Poet.” The Rocky Mount Telegram (Rocky Mount), March 20, 1966. Accessed November 4, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/340717920/?terms=%22george moses horton%22.

[3] Richard Walser. The black poet; being the remarkable story (partly told by himself) of George Moses Horton, a North Carolina slave. New York: Philosophical Library, 1966.

[4] McMakin, page 15.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “1800 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 04 November 2017), entry for William Horton, Hallifax, Northampton County, North Carolina.

[8] Walser, page 4.

[9] Ibid.

[10] McMakin, page 15.

[11] Walser, page 4-5.

[12] McMakin, page 15.

[13] Walser, page 5.

[14] Walser, page 7.

[15] Steelman, Ben. “George Moses Horton — love poet for hire.” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), October 03, 1974. Accessed November 4, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67849476/?terms=%22george%2Bmoses%2Bhorton%22.

[16] Walser, page 9.

[17] Walser, page 7.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Walser, page 15.

[20] George Moses Horton. The hope of liberty. Raleigh: J. Gates & Son, 1829.

[21] McMakin, page 15.

[22] Steelman, page 1.

[23] Walser, page 16.

[24] Walser, page 19.

[25] McMakin, page 15.

[26] Walser, page 19.

[27] Walser, page 19-20.

[28] Walser, page 20-21.

[29] Steelman, page 1.

[30] Walser, page 22.

[31] Steelman, page 1.

[32] June. “Flight Shots.” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), January 30, 1934. Accessed November 5, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67923489/?terms=%22george moses horton%22.

[33] Jennifer Schuessler. “In a Lost Essay, a Glimpse of an Elusive Poet and Slave.” The New York Times, September 25, 2017. Accessed December 4, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/25/arts/george-moses-horton-essay.html?_r=0.

[34] Walser, page 25.

[35] The Associated Press. “Work of slave poet is remembered.” The Rocky Mount Telegram, May 27, 1997. Accessed November 5, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/339220764/?terms=%22george%2Bmoses%2Bhorton%22.

[36] Walser, page 30.

[37] Steelman, page 1.

[38] Walser, page 34.

[39] The Southern Historical Collection. “Manumission Society of North Carolina Records, 1773-1845.” UNC University Libraries. Accessed December 04, 2017. http://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/02055/.

[40] Vance Mizelle. “Black Tarheel Profiles.” The Evening Telegram (Rocky Mount), April 04, 1974. Accessed November 5, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/336760746/?terms=%22george moses horton%22.

[41] Walser, page 35.

[42] Mizelle, page 6.

[43] Walser, page 40-41.

[44] Horton, The Hope of Liberty, page 2-3.

[45] Ibid.

[46] “State museum exhibition honors prominent blacks.” The Nashville Graphic, January 21, 1975. Accessed November 5, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/341068906/?terms=%22george moses horton%22.

[47] Walser, page 53-60.

[48] “Untitled.” George Moses Horton to David Lowry Swain. 3 September 1844. David L. Swain Papers (#706), Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[49] Walser, page 60-67.

[50] Steelman, page 1.

[51] McMakin, page 15.

[52] Walser, page 70-83.

[53] George Moses Horton. “An Address To Collegiates of the University of N.C.: The Stream of Liberty and Science By George M. Horton The Black Bard.” Speech transcript, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1859.

[54] Walser, page 84-85.

[55] Walser, page 88.

[56] Walser, page 91-97.

[57] George Moses Horton. Naked genius. Chapel Hill, NC: University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1866.

[58] Walser, page 98-100.

[59] McMakin, Martha. “Slave Wrote Poetry On Campus.” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), March 20, 1966. Accessed November 13, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67937958/?terms=%22george moses horton%22.

[60] George Moses Horton. “The Pleasures of a College Life.” In Pettigrew Family Papers (#592). Accessed November 13, 2017. Southern Historical Collection.

[61] Walser, page 100-102.

[62] George Moses Horton. The poetical works of George M. Horton, the colored bard of North Carolina: to which is prefixed the life of the author written by himself. Chapel Hill: D. Heartt, 1845.

[63] McMakin, page 3.

[64] Walser, page 104-106.

[65] Ibid.

[66] McMakin, page 3.

[67] Mizelle, page 6.

[68] Collier Cobb. “An American Man of Letters.” The University Magazine, October 1909, 2-10. Accessed November 13, 2017. https://archive.org/details/americanmanoflet121cobb.

[69] Benjamin Brawley, “Three Negro Poets: Horton, Mrs. Harper, and Whitman,” The Journal of Negro History (October 1917): 384-392.

[70] Joan R. Sherman, The Black Bard of North Carolina: George Moses Horton and His Poetry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 1.

[71] Walser, page 1-109.

[72] Sherman.

[73] Don Tate. Poet: the remarkable story of George Moses Horton. Atlanta: Peachtree, 2015.

[74] Sarah West. “UNC to commemorate George Moses Horton.” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill), July 10, 1980. Accessed November 13, 2017. https://www.newspapers.com/image/67936810/?terms=%22george%2Bmoses%2Bhorton%22.

[75] “George Moses Horton Award for Multicultural Leadership.” Chancellor’s Awards at Carolina. Accessed November 13, 2017. http://chancellorsawards.unc.edu/?page=awardrecipients&id=5.

[76] “Umoja Awards.” The Black Student Movement. Accessed November 13, 2017. http://www.uncbsm.com/umoja/.

[77] David R. Godschalk and Jonathan B. Howes. The Dynamic Decade: Creating the Sustainable Campus for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2001-2011. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

[78] Ibid.

[79] The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Alumni Review. “28 March 2006.” News release, March 28, 2006. Carolina Alumni Review. Accessed November 13, 2017. https://alumni.unc.edu/news/dorm-will-be-named-for-slave-poet-horton/.

[80] Schuman, page 1.

[81] The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, news release.

[82] “UNC-CH dorm to get slave’s name.” History News Network, April 6, 2006. Accessed November 13, 2017. http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/23682.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Schuman, page 1.

[85] James Moeser. “Dedication Speech.” Speech, Georges Moses Horton Residence Hall dedication, George Moses Horton Residence Hall, Chapel Hill, February 12, 2007. Accessed November 13, 2017. http://www.unc.edu/news/speeches/hortondedicationmoeser021207.html.

[86] The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2007 Campus Sustainability Report. Report. UNC Sustainability Office, The University of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, 2007.

[87] Cynthia Greenlee-Donnell. “UNC-Chapel Hill examines race and history.” Indy Week, October 18, 2006. Accessed November 13, 2017. https://www.indyweek.com/indyweek/unc-chapel-hill-examines-race-and-history/Content?oid=1199381.

[88] Schuman, page 1.

[89] Matthew Turi discussed this in a class visit to Wilson Library, where the class learned how to use archival materials and utilize the University Archives to understand the construction and naming of buildings.

[90] John Kenyon Chapman. Black freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960. Master’s diss., The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2006.