By Wesley Thompson

Wilson Library: A Century of Evolution

The Louis Round Wilson Library was meant to inspire pride in those who call the University of North Carolina home and impress anyone who had the opportunity to see it. Not only is this library an architectural beauty, but it has housed one of the most extensive collections of rare books, primary documents, and North Carolinian artifacts for the past century. But this library did not emerge from a need to impress academics or a need to beautify the University’s south campus, but from a need to keep up with the rapidly growing student body and their changing academic needs. Whereas the University library once belonged in Carnegie Library, now Hill Hall, the early twentieth century brought scores more of intelligent minds seeking to further increase their knowledge on increasingly varied topics. However, this pursuit brought them to a library that could no longer support their academic needs as books began piling up in Carnegie’s basement and study space was stretched thin. University President Chase recognized these problems as well, addressing them in a 1924 statement:

“The present building cannot be enlarged; the problem is not one of additions to the stacks, or of the construction of a large reading room, but of the erection of a building of a quite different plan throughout, to fit the changed needs of an institution grown not only larger but vastly more complex. In short, we have a library built for, and reflecting the needs of, a small college; our need is for one to meet the conditions of work in a university.”[1]

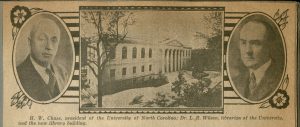

The library that would later be known as the Louis Round Wilson Library was his response to these problems. Plans for its construction and use were led by President Chase, John Sprunt Hill, and its eventual namesake, Louis Round Wilson. With a focus on expanding library collections, study space, and services, Wilson earned his name’s place on the library through his impressive career in library sciences, women and minority rights advocacy, and more than sixty years improving this university. The library changed as the student body changed, adapting to the increasing needs and size of the student body.

The Namesake

This hallowed hall is named for Louis Round Wilson, a man whose life and resume are almost as ornate and stunning as the Wilson Library itself is. Born in Lenoir, North Carolina to parents Jethro Reuben and Louisa Jane Round Wilson on December 27, 1876, Wilson began his long and

influential journey here when he transferred to The University of North Carolina from Haverford College in the fall of 1898 and graduated in May 1899 with a degree in English. In 1901 and after much deliberation on whether to pursue library science as a career or whether to seek a professorship in English elsewhere, he became the librarian at UNC as well as began his work towards his master’s degree which he received the following year and Ph.D. in 1905, both in English. Enchanted with the University and his potential here, Wilson remained in his role as librarian following graduation as well as expanded his role in the university from 1905 to 1907 where he became an assistant in the German department. He continued to develop a library collection for research and graduate studies that focused on the southern United States with a more specific, strong focus on his very own North Carolina.[2]

With a strong desire and vision to expand the university resources in rare books and incunabula, or books printed before the sixteenth century, Wilson created a collection of rare books still used in Wilson Library today. Seeing a need to expand the library facilities to accommodate the expanding student population, he also planned and supervised the construction of the Carnegie Library, now named Hill Hall, opening in 1907. The Carnegie Library, created as part of a national campaign to construct libraries by the Carnegie family, was the campus library until Wilson finished orchestrating the opening of what is now the Wilson Library in 1929, named after him in 1956.[3] Wilson was also a dear friend and colleague to University President Edward Kidder Graham during their time working at the university. Moreover, upon the sudden and untimely death of President Edward Kidder Graham in 1918 during the influenza epidemic here at UNC, Wilson proudly served as chair of the Graham Memorial Building committee. In the early years of his time at UNC, Wilson was absorbed in planning and supervising the building of the new library.[4]

Wilson trained many librarians and taught courses in the subject during the summer of 1904. Following his passion for advancing library science and using his experience to expand the field, he became assistant professor of Library Science in 1907 and Kenan Professor of Library Science in 1920. Not only was he a vital member of the UNC community and instrumental in the expansion of our own library system, he helped found and was an active member of multiple library associations in the South and nationally, often serving as president or chairman. He used these organizations and positions to advocate for federal aid to libraries. Wilson also wrote multiple articles about his profession in academic journals and newspapers, doing so on a local, regional, and national level. As a faculty member, he supported university extension services to promote agricultural education, serving on the Committee on Extension from 1911 to 1920 and as chair from 1912 to 1920. Wilson founded and edited the Alumni Review to reach out to North Carolinians and former students, was an editor for The University News Letter, and director of the University Press, a continuingly prolific body that is responsible for thousands of scholarly, acclaimed publications.[5]

After the 1929 opening of what would become the Wilson Library, Wilson left the university to travel Europe to return the following summer so he could get funding for a library school at UNC, for which he received $100,000 from Carnegie Corporation president Frederick P. Keppel. The school opened a year later for which Wilson served as the first dean. After leaving to become the Dean of the Graduate Library School at the University of Chicago in 1932 and returning to UNC in 1942, he taught until 1959 in the School of Library Science. Still desiring to be an active member of the UNC community in his older years, Wilson served as assistant to the president of the UNC system until 1969 when he was 93 years old.[6]

Wilson wrote about significant UNC events that were compiled into Louis Round Wilson’s Historical Sketches, which was published in October 1976 in honor of his one-hundredth birthday. Throughout his long, accomplished life, Wilson was also known to be a vocal supporter of racial equality, often being published in newspapers on the subject and with the North Carolina congressional delegation in support of civil rights legislation.[7]

The Increasing Need

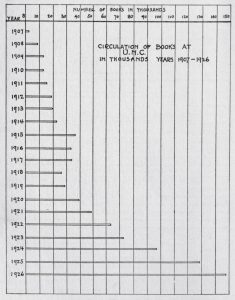

The appropriately honorific Wilson Library was created out of an apparent need of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to create a space large and well-constructed enough to support the expanding needs of the even more rapidly expanding student body. Studies were

done to determine if Carnegie Hall, what is now Hill Hall, would still be able to support the growing needs of the university. 99,914 books were loaned from the main desk during the 1923-24 school year. This number increased to 186,301 loaned during the 1927-28 school year, a year before the new library opened. In addition to the growing number of books loaned, the 1923-24 school year welcomed 14,232 new volumes in addition to the 139,015 already owned. During the 1927-1928 school year, 16,895 new volumes were added to the 198,472 volumes owned.[8] As evidenced by the stacks of books collecting in the basement of that building since 1923 and a student body quadrupling over the past decade in the 1920s, the studies conclusively said the university demanded a greater space to accommodate the needs of the students and further diversification of collections and materials, a pursuit very dear to Louis Round Wilson’s heart.[9]

Wilson dedicated a large portion of his time to helping to plan the new library and working to protect the interests of the student body whose interests and educational aspirations were changing as the university advanced. In his 1925 Librarian’s Report to the University President, Wilson took a firm stance on the growing need for a new library. “The present non-fireproof building was erected in 1906-07 at a cost of $44,000 to take care of a book collection ten numbering 40,000, and to provide reading room, seminars, and offices for a student body of 700 and a library staff of four members. Today the book collection numbers 15,060; new books are being added at a rate of from 12,000 to 15,000 volumes a year… the student body numbers 2300 and will, within the next three years, reach the 3,000 mark; and the library staff includes 14 full-time and 11 part-time members”.

Handwritten Graphs of Library Use by Wilson, Courtesy of The Librarian’s Report to the President 1924-25

Wilson also noted large sums of money had been allocated form the state by the university to improve the dormitories, class rooms, athletic fields, and service plants to support the growing student population. Yet, the library, which is utilized by the entirety of the University students, staff, and faculty, “the very heart of the University”, is still working out of the same facilities as 18 years prior. Wilson also determined that compared to the expansion of other major university libraries, 25,000 volumes would have to be moved into Person Hall and that if the collection is to expand to a quarter or half million volumes within the following decades, book storage must increase drastically as well as better centralization of materials, increased student study space, and avoiding the inevitable prohibitive maintenance costs that would accompany the fourteen-hour-a-day departmental library service that is present in the central library.[10]

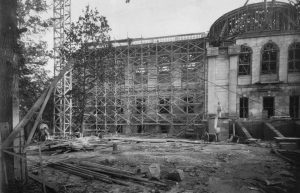

Construction of the New Library

Following a faculty meeting in September of 1924, Chase created a faculty committee to outline policy and prepare plans for a new building. Following the example of the plans and practices for the libraries at the University of Michigan, Minnesota, Chicago, and Yale, the committee determined the need for a greater concentration of library materials, building plans to allow for near indefinite future expansion, conform to the architectural plan of South campus, and contribute to “the general aesthetic charm” of the University.[11]

Wilson felt a distinct need to create a space that was properly expansive and attractive to welcome students to the “beating heart” of the university, as Wilson fondly called the library.[12] Arthur Cleveland Nash was tasked with the job of architect for this great endeavor, working closely with Wilson, University President Harry Woodburn Chase, and John Sprunt Hill, the Chair of the Trustee’s Building Committee throughout the 1920s. The planners had a clear vision for this building and its potential uses, making a point to build it in a way that it could be expanded in the future.

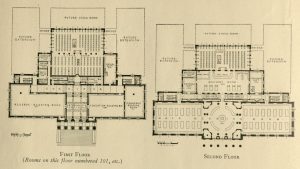

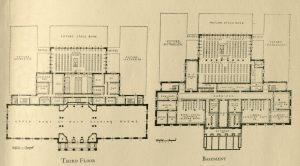

1930 Floor Plan for Wilson and Future Expansions, Courtesy of “The Library University of North Carolina 1929-1930” in “Dedication of University of North Carolina Library 1929”

As the library was the centerpiece of the university’s evolution into the modern era, these early leaders knew the library had to have a clear image of the significance of the university and would be impressive to all who see it, a trait that was clearly accomplished even into the present.[13] The building blends in with the other buildings in Polk Place in the style of colonial revival due to the large pillars, ample use of limestone and marble, and arched windows, yet towers far above and possesses much greater elegance on its both exterior and interior. Catherine Bishir in North Carolina Architecture defined the style and impact of Wilson well when she wrote, “The serenely confident composition, with its Corinthian portico and Roman dome, evokes the full grandeur of Beaux Arts neoclassicism and asserts the stature of the Library as the heart and symbol of a school emerging as a major modern university.” [14]

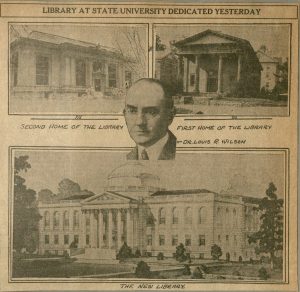

The Library Opening

The new library was completed in the autumn of 1929. Wilson had hoped that the Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam would give the dedication speech. After several nonresponses and an eventual agreement, Putnam declined at the last minute. Scrambling to find a replacement, Wilson invited Andrew Keogh, Librarian at Yale, to make what was reported to have been an unremarkable speech. The slow pace of planning the event was noticed by Robert House, who

Invitation to the Library’s Dedication, Courtesy of Dedication of the University of North Carolina Library 1929

admonished Wilson in a letter.[15] It is rumored John Sprunt Hill wanted the building named for him, but the resolution of naming was passed before the library was opened with Hill’s approval that it would be the University Library.[16] The library was dedicated by President Chase on October 19, 1929 with many University and State officials in attendance, along with members of the Citizens Library Movement of North Carolina, the North Carolina Library Association, the Southeastern Library Association, and many more parallel organizations. Governor O. Max Gardner presented the building to Hill, who accepted it on behalf of the University.[17]

Wilson also made known the gifts that were acquired by the library during its two years of construction in the order of money, books, plays, engravings, and manuscripts. One significant gift to the library came from the Hanes Foundation for the Study of the Origin and Development of the Book, established in 1928 to 1929 due to a generous gift $30,000 from the children of John Wesley and Anna Hodgin Hanes. The most significant portion of this gift was in the collection of three hundred and sixty six incunabula. It is also worthy to note that this large financial investment and these generous gifts were debuted ten days before the disastrous collapse of the stock market on Black Tuesday.[18]

The Library Expands

Also introduced in 1930 following the opening of the new University Library and made possible by a $25,000 gift from Mrs. Graham Kenan was the formal establishment of The Southern Historical Collection by the University Trustees with Dr. J.G. deRoulhac Hamilton, Kenan Professor and Head of the Department of History and Government, as director. Hamilton began a systematic search across the southern United States for letters, diaries, plantation records, business records, and other materials that still mark our collections as those of distinction. Wilson and Hill’s “Friends of the Library” provided donations and encouragement to the library administration.[19] The colonial style furniture for the North Carolina Reading Room was purchased with a $5,000 from John Sprunt Hill.[20]

Also in the wake of the library opening, the expanded space allowed a differentiation of collections and their spaces, likely causing the circulation of books to rise from an average of twelve books used a year per student previously to over 100 books a year in 1929.[21] Despite the stark increase in circulation, Wilson reported a distinct advance in the efficiency of many of the Library’s operations. The merging of libraries, such as that of the School of Education and Commerce and the Department of Rural Social-Economics, centralized many resources and coordinated formerly separated library functions. In addition, the preparation and practice of study and investigation was able to be more direct and concentrated which created a notable saving of time for students.[22]

After joining as assistant librarian in 1926, Robert Downs, alumnus from the class of 1926, replaced Wilson as university librarian in 1932. Downs increased the library’s collection and developed a significant bibliographic resource with the acquisition of a collection of six thousand volumes of national and subject bibliographies and cards previously secured from the Library of Congress.[23]

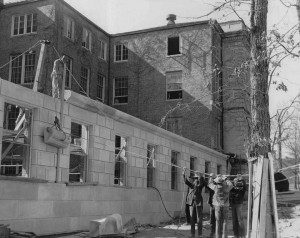

The 1952 Addition

The 1952 addition to the University Library, accompanied by the official name change to the Louis Round Wilson Library, was another example of a needed expansion due to a large increase in enrollment, this time due to the G.I. Bill. Additional funds were also being allocated to research and infrastructure in response to the prosperous economy, much like that during the

Library’s original construction.[24] As fields specialized and education became more focused during the Cold War era, additional journals and collections had to be created to support these new fields in science, this addition being the University’s response. It also is worth noting that these expansions of the addition of the wings, a stack expansion, increase in shelving capacity, new carrels, and the renovation and repurposing of elements of the original library frame were part of the original plan for the library, but the budget was reduced by legislature and the governor himself from $1 million to $625,000 during its original construction.

The renovation also included a Rare Books Room and space for the Southern Historical Collection, the North Carolina Collection Reading Room where the North Carolina Collection Gallery now resides, additional reading rooms, and improving structural integrity of the building.[25] The Librarian’s Report of 1952 stated the Assembly-Exhibition Room provides an “easily accessible and comfortable meeting place for groups, clubs and organizations on the campus and in Chapel Hill engaged in educational, civic and other cultural activities, as well as a center for exhibitions of artistic and library interest.”[26]

The 1977 and 1987 Addition

At some point after the 1952 addition an overall plan for library expansion began to take shape, focusing on adding another stack addition to the south side of Wilson Library, an undergraduate library east of Wilson, and a separate special collections library. After a fundraising campaign, money was raised to complete the first two goals and the remainder of money was applied to the better use of renovating Wilson towards being exclusively special collections and constructing the Davis Library. This was ultimately the better choice, as Wilson is much better suited for special collections due to its construction and the ability of Davis Library to host the number of students the university will continue growing to have.[27]

The renovations and restorations to Wilson Library from 1984 to 1987 were primarily within the building’s climate control to meet preservation standards, improving building and collection security, create exhibit spaces, create an assembly room, create spaces for public events, storage of materials, develop spaces for the use of the Manuscripts Department, the North Carolina Collection, and Rare Books Collection, allow space for the library’s map collection, and restore the Rare Books Reading Room and adjacent areas as far as possible to their original appearance. Other than the expanded stacks space, Wilson Library was then comprised of the four primary Special Collections from the library: the Manuscripts Department, the Rare Book Collection, the Maps Collection, and the North Carolina Collection.[28]

Museum Space on Campus

Since the beginning of this university, there were plans for a campus museum. Charles Wilson Harris, served as “Keeper of the Museum” until 1796, inspired by the curios at Kings College in New Jersey, his alma mater. He accepted various items such as an ostrich egg, beaver pelts, and other aspects of natural history, but there is no record these items were ever displayed in an actual museum fashion. Various men took over this role throughout the university history, but few actually developed any sort of exhibit.[29] The only items on display were normally local to particular department buildings or for short times in various campus buildings such as Person

Hall, Gerrard Hall, and Smith Hall. Wilson allowed the library to continue to accept artifacts and items with the intent that the items would be utilized for a future museum; however, exhibitions were not his focus. Photographs were taken of Carnegie Hall in 1921, showing exhibit cases and statues and the main reading room displaying oil paintings and trophies. This practice apparently continued until the new University Library was finished in 1929 and the items were then transferred there, yet only items such as books, pamphlets, and maps were displayed.[30]

During the 1920s and 1930s, as construction and renovation of University buildings continued, and as departments expanded or relocated, the use of exhibit cases and small display areas for special museum collections continued. In 1929, a new library building (later named for Louis Round Wilson) was completed, and the University Library was transferred to this new facility from Hill Hall (the old Carnegie Library). Exhibit cases were put in use there as well, although usually only library material—books, pamphlets, and maps—rather than museum artifacts were displayed.[31] In the University’s annual Report of the Librarian, Wilson describes the necessity of learning by handling things, citing the work of Henry Ford spawning from his time in an industrial plant, and how a fragment of a Babylonian tablet or a page from an ancient manuscript can make history real to its observer. He remarks, “The exhibit of such collections by a library awakens interest and fires imagination—is, in fact, an educational achievement of the first order. Lacking such exhibits and the means to make them public, the University Library lacks the power to make scholarship vivid. It has some collections of this sort, but it needs a great many more.”[32]

During the renovation and expansion of 1952, the historic rooms of the Sir Walter Raleigh Rooms and the Early Carolina Rooms were installed and described by Wilson as “unusually attractive features of the North Carolina section” of the library.[33] The Sir Walter Raleigh

Rooms feature sixteenth century paneling and furniture, as well as maps, an oil painting of Raleigh, and a large wooden statue of Raleigh from a tobacco shop.[34] These rooms were modeled after the typical gentleman’s library of the time of Sir Walter Raleigh, complete with original Jacobean English oak paneling of the late Tudor period (c. 1595-1610). The paneling is a gift from William Fahnestock, Jr. The furniture, also of the late Tudor period, is a donation from Mrs. Frederic M. Hanes.[35] The Early Carolina Rooms were modeled after an early eighteenth century home, the Lane House, erected in Pasquotank County. The yellow pine and cypress panels within the main room were also taken from the home. Two smaller rooms come from the side of the main room, originally intended to house books and small items contemporary to the rest of the home, however fire safety regulations have prevented those rooms from being utilized as exhibit space and the room itself from being able to be walked through as the Sir Walter Raleigh Rooms are.[36] These materials were purchased due to $1,000 gifts from Paul Green and John Sprunt Hill.[37] The Early Carolina Rooms were a now seen as slightly inaccurate portrayal of an early colonial home in North Carolina, painted by the fantasy etched into the mid-twentieth century colonial revivalism.[38]

The North Carolina Collection Gallery

The North Carolina Collection Gallery opened in 1989, emerging from the existing North Carolina Collection and housed in the former North Carolina Collection Rare Book Reading Room. Conceived by former NCC curator Dr. H.G. Jones and operated by the Gallery’s first Keeper R. Neil Fulghum, the Gallery began to display and exhibit the numerous items that had been collected by the library and other departments, all accomplished almost exclusively by the funding of John Sprunt Hill Trust Fund.[39] Fulghum designed all the exhibit spaces, work and storage areas, and acquired all that would be needed to continue this new space. The Gallery office, exhibition, and collections space then comprised the majority of the east wing of Wilson’s

second floor. The space contained the John Sprunt Hill Room, six display cases for rotating exhibits, and the historic rooms including the Sir Walter Raleigh Room, the Early Carolina Room, and the later addition of the Hayes Plantation Library in 1989.

The Hayes Library is a reproduction of the early nineteenth-century library at Edenton, North Carolina’s Hayes Plantation. The reproduction library here contains approximately 1,800 volumes, with imprints dating from the late 1500s to the 1860s, comprising the majority of literature original to the library. In addition to the majority of the original library’s books, the library here contains original furniture, and artwork, as well as retaining its notable octagonal shape and neo-Gothic elements. These items were donated to the North Carolina Collection by John Gilliam Wood, the present owner of Hayes. The original owner was James Cathcart Johnston, having the plantation house and its library built between 1814 and 1817 and designed by William Nichols, later the state architect of North Carolina. Through his father Samuel and his great-uncle, James inherited much of his literature, yet he amassed much more

during his lifetime to significantly increase its size and variety. Before the Civil War, this collection of Johnston’s was one of the largest libraries in North Carolina.[40] The books contained in the library are also available for use through the Rare Book Reading Room, housed on the opposite wing of Wilson’s second floor.

In addition, the Gallery still contains a large safe containing gold coins from the Charlotte and Bechtler Mints. Fulghum also was tasked to manage the installation of table cases in the Reading Rooms, portraits in Wilson’s lobby and hallways, and developing the Thomas Wolfe Room in the west wing of Wilson’s second floor, dedicated UNC alumnus and prolific author Thomas Wolfe.[41]

The NCC Gallery continues in the same operation of exhibition and preservation of artifacts important to North Carolina history. With approximately 32,000 items in its collection today, the gallery has advanced in ways of using computerized inventory systems, online exhibitions, blogs, and Artifacts of the Month. Linda Jacobson was hired as Assistant Keeper in 2003 and replaced Fulghum as Keeper in 2009. The Gallery now employs around four student employees and two full-time employees a year. The space was updated in 2013 to make exhibit space more current, reevaluate content, upgrade graphics on displays, and for the first time hire professional fabricators to improve the exhibits on natural history, Chang and Eng, The Lost Colony, and Sir Walter Raleigh. The North Carolina Collection Gallery has been written about in many North Carolina newspapers, including the campus newspaper The Daily Tar Heel, as well as newspapers as far away as Pennsylvania and New Jersey. These articles often attempt to tell the history of the North Carolina Collection Gallery, highlighting the James Audubon prints, the Chang and Eng exhibit, Napoleonic death mask, and the historic rooms, as well as feature interviews with Fulghum and NCC curator, H.G. Jones.[42] In continued efforts to improve the Gallery space, the Thomas Wolfe Room is proposed to be moved to what is now the Early Carolina Rooms and more interactive features like interactive kiosks will be added to the space and the Sir Walter Raleigh Rooms.[43]

Wilson Library Today

Since the library sits in the middle of campus, its steps have been home to many demonstrations protesting racism, sexism, and war. Living up to its original intent to appear intimidating, many myths persist about Wilson that contributes to smaller foot traffic than desired. There persists the myth that it is only a graduate library, perpetuated by orientation leaders and tour guides.[44] Decreased use may also be attributed to the no food or drink policy and overall quiet nature as it is the hub for primary document research as it contains the North Carolina Collection Research Library, Gallery, and Photographic Archives, the Southern Historical Collection, the Music Library, the Rare Book Reading Room, Southern Folklife Collection, the University Archives and Records Management Services, the Science Library Annex, the Center for Faculty Excellence, North Carolina Digital Heritage Center, as well as other presentation spaces like the Pleasants’ Family Presentation Room.[45]

What’s Important?

Louis Round Wilson remains very influential as librarian and professor at UNC and within the field of library science. He spent more than half a century at UNC, expanding their literary collection and acquiring finances to further expand it, as well as contributing to the construction of several buildings on campus. He also was the founder of the Library Sciences program here and taught within the program and the same program at the University of Chicago for the first half of the 20th century. While being a major player in the evolution of library science in the U.S., he also fought for the equal rights of minorities in the newspapers and in front of the North Carolina congressional delegation.[46] Wilson Library was a sorely needed addition to the campus due to the University Library no longer being able to support the size of the student body and the rate at which books had to be used by the end of the 1920s. Wilson Library even since has undergone multiple expansions to accommodate its growing literary collections and variety of uses as a museum space and rare book repository.

The Wilson Library has expanded as the needs of the student body have expanded, creating the special collections space that remain important today. A formidable building with an equally impressive past stands before anyone looking at the Louis Round Wilson Library on The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill campus. Sitting at the south end of the Polk Place Quad, the Wilson Library has been an architectural staple of the UNC campus for almost a century. Contained within the limestone and copper dome marked by verdigris, many additions have molded Wilson Library from the main campus library that was desperately needed to provide for the rapidly expanding student body in the economic bliss of the roaring 1920s through its continued expansions and renovations in the remainder of the twentieth century and the nascence of the twenty-first. From the Music Library, to the expansive Southern Historical

Grand Reading Room and Chandelier 1929, Courtesy of the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

Collection, and the massive reading rooms that bring you back to the architectural beauty of the early twentieth century with its vaulted ceilings and stunning chandelier, history remains a priority within Wilson. Yet, with almost a dozen different special features within Wilson Library created over almost a century of serving the University, researchers, and the inquisitive public, there is almost no end to what this building now offers.

Additional Resources

Wilson Library: http://library.unc.edu/wilson/about/wilsonhistory/

Louis Round Wilson: https://unchistory.web.unc.edu/building-narratives/louis-round-wilson/

https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/wilson-louis-round

Louis Round Wilson’s Historical Sketches (Southern Historical Collection)

Library Growth and Special Collections: The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina (Southern Historical Collection)

[1] Louis R. Wilson, The University of North Carolina, 1900-1930: The Making of a Modern University (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957), 384-385.

[2] Weaver, Frances A. “Wilson, Louis Round.” In Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. University of North Carolina Press, 1996. https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/wilson-louis-round.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Wilson, Louis Round. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, 1924.; Wilson, Louis Round. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, 1928.

[9] Hewitt, Joe A. “Louis Round Wilson Library: An Enduring Monument to Learning.” UNC University Libraries. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, October 21, 2004. http://library.unc.edu/wilson/about/wilsonhistory/.

[10] Wilson, Louis Round. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, 1925.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Hewitt.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Bishir, Catherine W. North Carolina Architecture. University of North Carolina: UNC Press Books, 2005.; quoted in Hewitt.

[15] Jacobson, Linda. “Wilson Library.” NCC Gallery Records, n.d.

[16] Hewitt.

[17] Jacobson.

[18] McGrath, Eileen, and Linda Jacobson. The Great Depression and Its Impact on an Emerging Research Library: The University of North Carolina Library, 1929-1941. UNC University Libraries. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2011.

[19] Jacobson.

[20] Wilson, Louis Round. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, 1930.

[21] Hewitt.

[22] Wilson. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. 1930.

[23] Jacobson.

[24] Hewitt.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Wilson, Louis Round. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, 1952.

[27] Hewitt.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Fulghum, R. Neil. “The North Carolina Collection Gallery.” NCC Gallery Records, n.d.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Wilson, Louis Round. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, 1928.

[33] Wilson, Louis Round. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, 1951.

[34] Lounsbury, Carl. “A Review of the Early Carolina Rooms in the North Carolina Collection.” NCC Gallery Records, March 15, 2016.

[35] Wilson. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. 1951.

[36] Lounsbury.

[37] Wilson. The Report of the Librarian of the University of North Carolina. 1951.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Fulghum.

[40] “Hayes Library.” The Louis Round Wilson Library Special Collections. University of North Carolina: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Accessed 12/3/17. http://library.unc.edu/wilson/gallery/hayes-library/.

[41] Fulghum.

[42] O’Neal, Glenn. “North Carolina Gallery Houses 400 Years of State History.” The Daily Tar Heel. December 3, 1990. https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/67830632/?terms=north+carolina+collection+gallery.; “North Carolina Gallery Houses 400 Years of State History.” Asbury Park Press. March 14, 2004. https://universityofnorthcarolinaatchapelhill.newspapers.com/image/144452651/?terms=north%2Bcarolina%2Bcollection%2Bgallery&match=23.; Carpenter, Mackenzie. “A Mystery Behind the Mask.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 19, 2013. http://www.post-gazette.com/life/lifestyle/2013/06/19/Is-mask-on-the-auction-block-really-Napoleon-s-death-mask/stories/201306190130

[43] Personal interview, Linda Jacobson, Keeper, 11/10/17.

[44] Personal tour, n.d.

[45] “The Louis Round Library Special Collections.” UNC University Libraries. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Accessed 10/8/17. http://library.unc.edu/wilson/.

[46] Weaver.