by Ellen Saunders Duncan

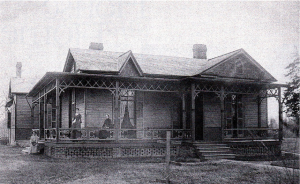

To the casual visitor, the boundary of campus’s northeastern-most edges aren’t especially clear. The quads of academic buildings shift to dormitories, and then campus almost dissipates into the surrounding neighborhoods of large historic homes. But at the corner of East Franklin Street and Battle Lane, at the farthest-flung corner of campus, stands the Love House and Hutchins Forum. With its broad expanse of lawn, steep white gables and wide front porch replete with rocking chairs, Love House seems like the perfect Southern college-town home. And in fact, it is. Love House is the vantage point from which generations of southerners have negotiated changing notions of higher education; that trajectory has culminated in its current iteration as a place where the university works to understand Southern identity.

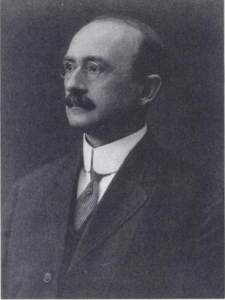

Nicknamed “The House of the Seven Gables,” Love House was designed and built in 1887, by the newly-wed James Lee Love and Julia James “June” Spencer Love, who lived there with her mother, Cornelia Phillips Spencer.[1] James was a native of Gastonia, part of a family deeply connected to agriculture, millwork and textiles.[2] A brilliant student at Carolina, he won the Phillips Mathematical Prize in 1882, and graduated in 1884 as valedictorian, class president, and winner of the Mangum Medal for best graduating oration.[3] In Love’s valedictory address “The New North State,” he reflected on a shifting sense of southern and North Carolinian identity, speaking “gracefully and strongly of the causes transforming the old into the new State.”[4]

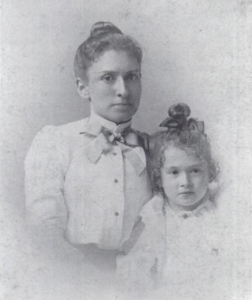

June was considered to be one of Chapel Hill’s most eligible young women. The daughter of Cornelia Ann Phillips Spencer and James Monroe Spencer, June grew up in a Chapel Hill academic dynasty.[5][6] June’s mother was the youngest child and only daughter of James and Julia Vermeule Phillips.[7]

Both were deeply committed to education: James was a long-time professor of mathematics at the University, and Julia was classically educated, tutored her children, and later opened a school for girls in Chapel Hill. The Phillips children were exceptionally well educated, and Cornelia’s older brothers Charles and Samuel entered the University in 1837. As a woman, Cornelia was barred from attending UNC, but her commitment to the University and to education became her life’s work.

Cornelia Phillips Spencer is a confounding and paradoxical figure in the University’s history. The dominant remembrance of Cornelia Spencer has been as “the woman who rang the bell” to re-open the University in 1875, but that vision of her has shifted in recent decades, as more attention has been given to her promotion of racist, white supremacist ideas. She was a prolific writer of poetry, and historical and social criticism. As an exceptionally educated woman distanced from plantation culture, she was “uniquely positioned” to critique the societal structure of the antebellum South, but instead joined a group of southern female writers who advocated for the Lost Cause, arguing for white supremacy, traditional values and ideals, and a return to the old social order.[8]

Cornelia Spencer became a loud and important voice for conservatism in North Carolina, allying with political figures like Zebulon Vance, Paul Cameron, Kemp Battle and William Saunders, to advocate for the re-opening of the University under the control of their white supremacist Democratic Party. Though much of her writing focused on the expansion of quality public education for all North Carolinians – male and female, black and white – her arguments were motivated more by a boon for economic development and the public good than an emphasis on equality. Cornelia Spencer was emphatically not a feminist, arguing that women were intended to be wives and mothers, and that they did not need rights equal to men’s in order to accomplish those roles. She felt that education for women should enhance their natural talents and interests, facilitating genuine engagement with subjects rather than a superficial veneer of knowledge; this was tempered with her admonishment that too much education, particularly in areas like math, science and economics, would lead women to be unattractive and “uninviting.”[9]

Like her mother before her, June had academic advantages and opportunities well beyond most women of her time. Particularly talented in the visual arts, she studied painting at the Cooper Union in New York, and later traveled to Europe to study there.[10] She taught art at Peace Institute in Raleigh in the early 1880s, and toward the end of the decade, she held a school for young children on the grounds of Senlac in Chapel Hill.[11][12]

* * *

Though James and June first crossed paths in August of 1881, when he was first starting at the University, they were not formally introduced until the summer of 1883. They were engaged during the Christmas vacation of 1883 and married two years later, on December 23, 1885.[13] [14] Notably, just days before James and June were engaged, she received another marriage proposal.[15] This offer of marriage came from Francis Venable, who had already earned masters and doctorate degrees, and who held a secure faculty position as the chair of the Chemistry Department.[16]

By all accounts, James and June had a very happy and successful marriage, grounded in “the soundest and best sort of basis of mutual confidence and congeniality.”[17] In his memoirs, James recounted their relationship as one of intellectual peers, a dynamic notable for its progressiveness and its divergence from June’s mother’s stance that women were subordinate – though not inferior – to men.[18] During their engagement, when James settled on teaching mathematics as the work he wanted to pursue, it was a choice they made together, “that would best satisfy both of [them]… offering a career of useful and dignified service where both…could, perhaps, do the most good together.”[19] [20] It is this question – how might academia provide the opportunity to do “useful and dignified service” and contribute to the greater good – that would complicate the Loves’ lives.

* * *

For James and June Love, and Cornelia Spencer, the University of North Carolina was a cultural entity that they felt easy ownership of. The student body was largely composed of young men similar to James Love: the privileged sons of men who were successful in the agricultural South. The universe that surrounded the University was small and close-knit; Chapel Hill was a village built to support the college, and families, like the Phillips-Spencers, who lived there all had a particular utility to the institution. And so, while the University of North Carolina is, and was, the country’s first public university, it seemed personal and private to people like Cornelia Spencer, and James and June Spencer Love; for elite southerners, ‘the public’ was much smaller than the country’s, or the South’s, or even North Carolina’s total populace. This tacit ownership of a public institution would become destabilized as the rhetorical purpose of the University was re-understood. Essentially, asking the questions “Who is the public university for? What purposes does the university serve?” in the post-Reconstruction South would lead to rapidly diverging and complicating senses of what constituted education for ‘the public good.’

* * *

In 1885, the state legislature increased funding for the University, allowing for more professors to be hired.[21] One of the new positions was an assistant professorship in Mathematics, and President Battle asked James Love to apply. Love was completing a fellowship at Johns Hopkins, but returned to Chapel Hill to begin teaching in the fall of 1885.[22] [23] His selection to this position was not without controversy, with accusations of favoritism lodged against Battle for choosing the son-in-law of one of his close political allies.[24]

Beginning in his second year of teaching, James Love also served as Secretary of the Faculty. As he describes it, the role had relatively few responsibilities — “[it] meant only that I kept a record…of Faculty Meetings, which were held weekly in President Battle’s office. President Battle took care of all correspondence himself; and each professor prepared and looked after all the admission examinations…of students entering his courses.” But this role strengthened his political ties to President Battle, which would be consequential later. In January 1887, James and June Love were invited to move into President Battle’s house, Senlac, to stay with Battle’s family while he was in Raleigh to protect the University’s Land Grant funding in the legislative session.[25] June and James Love lived there with the Battles until their own home — Love House — was completed late in the summer of 1887.

* * *

In the late 1880s, the University was growing, but housing for faculty did not keep pace. Thus the University devised a plan to help faculty members to build homes. Kemp Battle described the circumstances:

In 1886 was begun the policy of leasing land on Franklin Street and its continuation eastward to officers of the University for residences. The Circuit Court of the United States had decided, as has been narrated, that, as this is a State University, such property as is essential to its existence could not be alienated. The court laid off about 600 acres in one body, including the Campus and three residences of Professors, as inalienable. Believing that, although this land could not be sold in fee, leases for years could be made, a valuable parcel was granted to Mr. James Lee Love for fifty years on payment of a moderate annual rent. It was stipulated that at the end of that time the lease should be renewable, but if not, the Trustees should have the option to buy the tenements at an appraised value, but if they should not wish to do this the lessee might remove the buildings. The object was to provide that the land should not go permanently from the University.[26]

The lease made to the Loves was the first of this kind, but similar ones were also made with other faculty, and eventually the University sold lots to faculty outright.[27]

June and James began planning their house in the spring of 1887. The lot on which it was built was originally part of Lot 19 in the first survey of the University, conducted in 1793. In 1811, President Joseph Caldwell and his second wife, Helen Hogg Hooper built what became known as the “Second President’s House” on the site.[28] [29] That house was occupied by a series of University faculty and presidents concluding with Rev. Dr. Thomas Hume, a Baptist minister and professor of English, who moved in the day before the house burned down on Christmas Day 1886.[30]

In a meeting on April 20, 1887, the Board of Trustees made several key decisions, initiated by Pres. Battle, regarding the lot where the Second President’s House had been. First, the trustees decided to construct a road 33-feet wide on the eastern edge of the lot;[31] this became Battle Lane, but was called Caldwell Street early on.[32] The remaining lot was divided equally, north-to-south, and a lease was made to James Love for the eastern half, while the western half was leased to Rev. Dr. Thomas Hume, though he never built on it. Later, in 1900, the trustees sent a resolution “to the Executive Committee to consider…the practicality of building a suitable house for the President upon the site of the residence occupied by President Swain at the time of his death.”[34] The house that was ultimately built is the current President’s House, completed in 1906. However, the President’s House lot is larger than the original one-half, and the deed for the sale of Love House and its lot in 1906 shows the lot as 40 feet narrower than it originally was in the lease to James Love.[35]

The diagram on the right shows Lot 19 as it was partitioned in 1887, creating, from left to right, a lot for Thomas Hume, a lot for James Love, and Battle Lane. The lot line was redrawn in 1900, to accommodate the President’s House, which would be built six years later.

* * *

Love House was designed in anticipation that June’s mother would live there, too, and James’ parents also had significant influence on design and construction. Initially June and James wanted to build their house further east on Franklin Street, opposite of where the Horace Williams House is, but James’ father suggested the lot where it was ultimately built. James’ father also lent the Loves the money for the house; initially construction was planned to cost $1500, but it ended up totaling over $3000. The lot itself was leased for a fee of $15 per year.[36]

The design of Love House was inspired by James’ parents’ house in Gastonia. June and James liked the one-story design, thinking it more efficient for housekeeping. On the west side of the house, from front to back were James’ study, their bedroom, their dressing room, and a guest bedroom, and on the east side of the house were the parlor, Mrs. Spencer’s room, a turn in the hallway leading to the dining room, and finally the kitchen and pantry.[37] [38] A wide porch wrapped around two sides of the house, leading to large gardens, full of fruit trees, vegetables, and flowers, that June built with the assistance of a hired African American gardener named Roman Jones. This garden was a particular source of joy and pride for June, and the opportunity to feed themselves from their own garden deepened the connection the Loves felt with their home and with the land itself.[39] But James Love later wrote, “An evil fate seems to pursue a teacher who builds a house. Our enjoyment of our home was short-lived.”[40] James would leave Chapel Hill just two years later in 1889, with June joining him the next year. What does it mean, ultimately, that a house so invested with aspiration and confidence and optimism would so quickly come to symbolize a failed promise?

* * *

The conditions that precipitated James Love’s departure from the faculty were complex — some were emblematic of significant shifts occurring in higher education, some were politically specific to this university – but they broadly indicated a change in how the University of North Carolina understood its purpose. And further, the legacy of the structural changes that unseated the Loves is what made Love House a fitting home for it’s eventual resident: the Center for the Study of the American South.

* * *

The year 1890 marks a turning point in higher education, as colleges began transforming into modern universities. This shift was predicated on two trends that carried very different intent: first, the full realization and implementation of the Land Grant Act of 1862, and second, the promotion of research and scholarship as the dominant pursuit of academia.

The Land Grant Act provided federal land to states to endow the development of higher education focused on “agriculture and the mechanical arts,” intending to advance the public good by investing in the work and industries of most Americans.[41] [42] This legislation was implemented over the next decades, empowering states to realize “far-reaching aims to institutionalize practical fields of study, meld them with liberal education, [and] open them to a new class of students.”[43] It would seem that the South would particularly benefit from this development, essentially providing the opportunity to transform the region’s agrarian economy, postbellum.

At the same time, the first graduate programs were being developed at American universities, shifting the emphasis of the academy from teaching to scholarship and research.[44] Johns Hopkins University opened in 1876, with the first graduate students in the United States, and by 1889, had graduated 151 Ph.D.’s, far more than the combined total from the only other American graduate school programs, Harvard and Yale.[45] While these two trends contributed to the rapid expansion of American higher education, they also created a schism in the rhetorical purpose of education. The culture and intent of classical education traditionally afforded to only very elite Americans was fundamentally at odds with the democratization of education through the advancement of the work and public good of the majority of the American populace. As state legislatures and state and private colleges contended with these goals, higher education became increasingly stratified.

* * *

In North Carolina, the legislature appropriated the Land Grant endowment to the University of North Carolina, which helped facilitate its reopening in 1875.[46] However, efforts to incorporate curricula on agriculture and the mechanic arts, the primary requirement of the Land Grant legislation, were eventually perceived as a fundamental conflict with the culture and intent of the University.[47] Culminating at the 1887 legislative session, a political campaign was mounted to remove the Land Grant endowment from the University, for the establishment of a separate college that would focus on more practical education, in agriculture and the mechanic arts; this new college would eventually become North Carolina State University.[48] [49] The funding that was removed constituted roughly a third of the yearly appropriation from the state, and because Pres. Battle was unable to successfully lobby for other money, three faculty positions were immediately cut to meet the shortfall. Love’s position would be next; he managed to hold onto his job for the 1888-1889 year, though he gained more responsibilities, namely cataloguing and reorganizing the library, which had never reopened after the University’s closure in 1870.[50]

The University essentially found itself within an identity crisis, unable to clearly articulate what kind of education it was meant to offer to what kind of ‘public’. In order to reopen in 1875 and reestablish its traditional purpose of offering a classical education to North Carolina’s young people, the University took on a mandate to expand its public meaning. The University needed to be accessible to a broader range of potential students, and it needed to expand its definition of what disciplines were worthy of study and scholarship. But by the mid- to late-1880s, the University had failed at both, and the funding meant to strengthen classical education and develop practical education was removed. The result of this crisis was that the University presented increasing opportunities to a broader public, but the cost was that its traditional constituent, James Love, was no longer at home.

* * *

During Love’s last year at the University, 1888 to 1889, the Mathematics Department chair, Professor Ralph Henry Graves Jr., committed suicide, and appointing his successor became a politicized conflict. Several professors — Venable, Winston and Manning — were agitating for the removal of Dr. Battle from the university presidency, and used the circumstance to weaken Battle, as well as people who were close to him, including Mrs. Spencer and James Love.[51] Most critical in maneuvering Love off the faculty, Professor Winston argued that the new Mathematics Department chair should have a post-graduate degree or prior significant teaching experience. Love’s credentials were insufficient: he had just one year of postgraduate study at Johns Hopkins before returning to Chapel Hill in 1885, and was in his fourth year of teaching.[52]

In the school year of 1889 to 1890, James left Chapel Hill, after being appointed to a Morgan Fellowship in Mathematics at Harvard. He wrote, “We were facing the cold facts (1) that we must give up our nice new home, (2) that June and Mrs. Spencer must give up Chapel Hill, ultimately; and (3) that we must be separated during the year 1889-1890 so that I might study at Harvard.”[53] The separation was very difficult — “tragically painful,” “literally hell,” and “a serious mistake.”[54] Ultimately, a number of factors coalesced to make staying in Chapel Hill untenable. First and foremost, James Love aspired toward the traditional values of the academy: scholarship in the vein of classical education. Further, he prioritized his family’s unity and stability, and needed to earn a substantive income to support that. Opportunities that would resolve these concerns were not to be found at a southern, public college.

When he graduated from Carolina in 1884, James Love misjudged the changing conditions of American higher education, and underestimated how essential earning a Ph.D. would become. Both of the fellowships he held – at Johns Hopkins in 1884-85, and at Harvard in 1889-90 – could have been parlayed toward earning a Ph.D., but neither instance panned out, given his obligations toward his personal life, as well as other conditions. In essence, though his preparation up to that point had been consistent with the studies of his professors and mentors, just a few years into James Love’s academic career, those same high-level scholarly positions now required a degree which he did not have, and wasn’t in the position to earn. Lacking the credentials to pursue scholarly positions, Love became an instructor, and eventually assistant professor, in the Lawrence Scientific School,[56] Radcliffe College, and Harvard’s Summer School, and then onto administrative positions there. [57] [58]

The Loves had two children, Cornelia, born 1892, and Spencer, born 1896. Cornelia and Spencer grew up in Cambridge, and attended Radcliffe and Harvard, respectively. Their parents raised them there specifically because of the quality of education available; in a 1975 interview, Cornelia Love recalled that her father had been offered the presidency of Tulane University in New Orleans, but “turned it down because [James and June] knew that the southern schools couldn’t compare.”[59] [60] All of the family ultimately returned to North Carolina, though, and James Love left academia to become a businessman. Cornelia moved to Chapel Hill in 1917, and worked in the UNC Library, retiring in 1948 as the head of the orders department. [61] In 1919, James, June and Spencer Love purchased the Gastonia Cotton Manufacturing Company from James’ brother and other family members. Spencer Love would ultimately parlay this family mill into Burlington Industries, which would grow to become the largest textile business in the world.[62] [63]

* * *

After the Loves left for Cambridge, Cornelia Spencer remained at Love House until the summer of 1894, when she joined her daughter’s household in Massachusetts.[64] [65] That she only departed Chapel Hill under the duress of serious health issues reflects the deep-seeded commitment Cornelia Spencer felt to the place; but is also reflects an expansion of the University’s meaning and purpose to different people. Caught in a deepening identity crisis, it failed to fulfill its traditional promise, a classical education and then employment as a professor, for its traditional constituency, the brightest privileged sons of the South’s planter and merchant classes. Ultimately, to fulfill his aspirations toward the traditional understanding of the academy, James Love had to move away from the South, and leave the public university. Though Love House had been conceived of and built assuming a clear sense of place at the University for a young academic family, that purpose would be unfulfilled by the evolving state of higher education.

In juxtaposition, the University remained acquiescent to Cornelia Spencer’s relationship to it. In her role as one of the University’s most prominent advocates, fundamentally a public figure, she was able to perpetuate her close relationship to the institution as its purpose became focused toward the benefit of a larger public good. This outcome is paradoxical: Cornelia Spencer simultaneously valued the old order and the continued supremacy of elite white southerners, but she also promoted quality education for North Carolina’s populace. While her daughter and son-in-law departed to fulfill lofty aspirations in more rarefied academic circles, Cornelia Spencer was caught between both elitist and populist ambitions.

But maybe this shouldn’t be surprising. Cornelia Spencer was fundamentally an outsider to the University: because she could not actually study there, she took a front row seat and advocated for its success. Though the democratization of the University might outwardly offend her values, perhaps Cornelia Spencer’s role may have been as an instigator of the expanding purpose of higher education. And further, her bond to the institution anticipates the sentiment that elevates the importance of the University of North Carolina for many, many people; as Charles Kuralt asked at the University’s bicentennial in 1993, “What is it that binds us to this place as to no other? …our love for this place is based on the fact that it is as it was meant to be, the University of the people.”[66]

* * *

The Loves’ departure from Chapel Hill made way for subsequent residents of their home to participate in the democratization of the University, and of higher education in the South. Dr. Richard Whitehead, who lived in the house from 1894 to 1906, oversaw the development of the Medical School into a comprehensive curriculum, with faculty recognized for excellent scholarship.[67] [68] The house’s next residents were Henry H. “Hoot” Patterson and his family. Patterson was a businessman whose opportunities developed largely because of Chapel Hill’s burgeoning growth; he owned one of the main general stores in Chapel Hill, was a director of the Bank of Chapel Hill,[69] and started the town’s first telephone company,[70] in addition to serving various civic roles. In subsequent generations, Love House was leased on one-year terms by the university to various faculty members, including, for many years, the Commanders of the University’s Naval ROTC program.

* * *

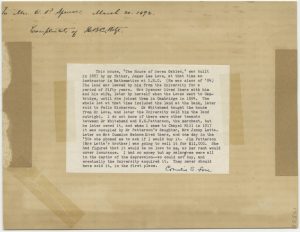

In parallel to its diverse and sometimes unknowable series of residents, Love House has an unusual history in terms of ownership. When the House was built in 1887, the Loves owned the physical structure, but leased the land on which it was built. When the house was sold to Dr. Whitehead in 1894, the same arrangement continued, but when Henry Patterson purchased the house in 1906, the University also sold the land to him. In 1915, the lot was subdivided, and the back portion was sold to Felix Hickerson, who built Hickerson House there. The Patterson family  continued to own the house and land into the 1930s. One of the Patterson daughters lived there with her family, and eventually the house was rented to tenants.[71] One such tenant proposed to Cornelia Love that she might purchase the house her parents had built decades earlier:

continued to own the house and land into the 1930s. One of the Patterson daughters lived there with her family, and eventually the house was rented to tenants.[71] One such tenant proposed to Cornelia Love that she might purchase the house her parents had built decades earlier:

“…one day in the ‘30s she phoned me to ask if I would buy it. [The] Pattersons… [were] going to sell it for $11,000. She had figured that it would be no loss to me, as her rent would cover insurance. I had no money but my salary – we were all in the depths of the depression – so could not buy, and eventually the University acquired it. [My parents] never should have sold it, in the first place.”[72]

As Cornelia Love remembered, the University did indeed purchase the house and its land: for $6500 on July 21, 1942 from A.N. and L.L. Stainback.[73] [74] It has been publicly owned ever since.

* * *

The last family to live in Love House was Spencie Love’s. Spencie was a granddaughter of James and June Love, and a daughter of Spencer Love. After working as a journalist, historian and writer, she served as the Assistant Director of the Southern Oral History Program from 1998 to 2000.[75] Her family resided in the Love House from 1998 to 2003,[76] and her contributions were critical to Love House’s most recent transformation. In 2003, the University conducted a Historic Preservation Survey and found the Love House to need significant repair work; for that restoration to be undertaken, the house needed to be converted from a university-owned private residence to a research center.[77] Early on, the Center for the Study of the American South was suggested as a fitting resident for Love House. In September of 2003, Chancellor James Moeser mentioned the possibility in an email to an alumni-donor, writing, “[former University President] Bill Friday tells me that Spencie Love, the granddaughter of the original Love, has indicated a willingness to provide a gift that might be sufficient to renovate the house as an appropriate home for the Center.”[78] The cost of the renovation would total nearly $1 million, and financial backing came from a number of different sources, including the Martha and Spencer Love Foundation.[79] This donation became a flashpoint in another debate on campus about naming and the history we choose to remember.

Beginning in 2002, a campaign by a graduate student at the University, Yonni Chapman, brought attention to Cornelia Phillips Spencer, and questioned how the University understood her, and her work and beliefs, and the University’s choice to commemorate her with the Cornelia Phillips Spencer Bell Award.[80][81] This activism focused especially on her writing, and required the University to reconsider Spencer’s white supremacist beliefs, and how using her name in conjunction with a prestigious award functioned to celebrate those ideas, which are ostensibly part of the University’s past, but not present. Poignantly, the campaign argued that, “UNC can never be a university for all women, let alone ‘the University of the People,’ until we can openly, honestly, and seriously discuss the implications of our history and current practices.”[82] Ultimately, Chancellor Moeser decided to retire the award in late 2004.[83][84] In response, Spencer’s descendants asked the University to redirect the Love Foundation’s donation away from the restoration of Love House for the Center for the Study of the American South; moreover, the Love family wanted to dissolve their connection to CSAS and the University’s Southern Studies programs.[85] The Love family came to a compromise several weeks later in a meeting with University figures, including Chancellor Moeser, former University President Bill Friday, and CSAS director Dr. Harry Watson, and the family’s donation toward the Love House renovation held.[86] [87]

* * *

In daily life at Carolina, the University’s geographic and regional context isn’t necessarily the most predominant factor in how identity here is defined. For many people, the University’s southern-ness is incidental; for others, it is a constant and intrinsic quality in determining culture and identity. As the oldest public university in the country, and second-oldest institution of higher education in the South, after William & Mary, the University has an intellectual and cultural responsibility to wrestle with what it means to be southern.

The entity within the university community that most embraces and confronts southern identity today is the Center for the Study of the American South, the current resident of the Love House. Founded in 1992, the Center defines itself as an extension of “UNC’s historic role as the world’s premier institution for research, teaching, and public dialogue on the U.S. South.”[88] The Center both “confirm[s] Carolina’s long-standing commitment to its own region” and fosters interdisciplinary scholarship “exploring every aspect of the South’s rich though often painful past and support[ing] the region’s democratic and progressive future.”[89] [90] Ambitiously, the University has declared that, “scholarship of this character will enable the Center to embody the University’s highest moral values and become the intellectual nucleus for creative transformation of the entire region.”[91]

* * *

In the Center’s work, the South’s past and present are vividly expressed in complex terms. This means presenting lecture series and cultural events, funding multidisciplinary research and conferences, housing the Southern Oral History Program, and publishing Southern Cultures, a peer-reviewed quarterly journal. In sum, the Center for the Study of the American South engages a constantly shifting range of disciplines, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks to complicate and negotiate Southern identity.

In the early 2000s, the University committed to consolidating and strengthening the various programs addressed toward the South. The Center for the Study of the American South was reconfigured to include not only the Southern Oral History Program and Southern Cultures, but also the now-closed Program in Southern Politics, Media, and Public Life.[1][2] All of the various parts of CSAS would now be housed in one building, rather than spread across several offices.[3] An advisory board for CSAS was initiated,[4] and three distinguished professorships were endowed for Southern studies faculty.[5] A campaign was launched to raise funds to support these developments. Apart from the Love Foundation’s contribution toward the House’s renovation, the most significant donation came from Glenn Hutchins to honor his father, James A. Hutchins, Jr., a graduate in the Class of 1937. James A. Hutchins, Jr., was a star football player for UNC, and studied under Howard Odum, the noted sociologist; Hutchins led various hunger- and poverty-alleviation initiatives, advocating on behalf of domestic farmers and the urban and rural poor.[6] Hutchins’ name joined Love’s on the structure as it was expanded with a sizeable addition to the back of the house.[7] [8] [9] Initially intended to total 900 square feet, the addition was increased to 1600 square feet to accommodate a request from the Chapel Hill Preservation Society that areas of the original house be kept as period rooms, consistent with the design and décor of the House’s early years.[10] In a 2002 letter, Chancellor Moeser reflected on these efforts, “I promised…that I would do all in my power to make sure that Chapel Hill remained at the top of the game in [Southern Studies]. Rather than living on our glorious past, we are truly building for the future.”[11]

* * *

Love House’s location carries significant symbolic weight. The entity that directly questions our University’s southern-ness is the next-door neighbor to the President’s House, home to the president of the consolidated University of North Carolina system. The transition of Love House from a private public space – publicly-owned but requiring power or connections to enter – to a truly public space – where everyone is welcomed to gather, whether on the lawn for a concert or on the porch for a conversation or inside for a seminar – mirrors the democratizing of Southern voices and identity occurring through the discipline of Southern Studies. The transformation of Love House’s powerful position and purpose is made all the more meaningful because it is in direct conversation with the home, the seat of power, for North Carolina’s democratized public university system.

The Love House reopened as the Center for the Study of the American South on April 21, 2007. Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the Harvard scholar, historian and cultural critic, gave the dedication.[12] Of the event, Paul Jones[13] wrote, “The House is of special historic interest in many ways. This move to a historic house and a notable home says a lot about how the South is constructed in our minds and in our experiences. Having Dr. Gates [as] the speaker indicates a nuance of that construction a kind of recognition of rooms left unvisited even in [a] small house.”[14] This is deeply and resoundingly true: there is a way in which the university is both ignorant of and ambivalent toward its southern identity, despite its intrinsic quality. We consider our southern-ness less than we do our broadened purpose to a more diverse and complex public, even though they are inextricably linked. Our southern-ness is intimate and perpetual — we know it deeply, perhaps more than we can even comprehend — while equally realizing that the bounds of that knowledge are limitless: there is always more to discover and question.

_____________________________

[1] Julia James Spencer Love was given the nickname June when she was born on June 1, 1859, and went by that name for her entire life. The vast majority of historical documents refer to her as June. James Lee Love went by his middle name familiarly, though historical sources are inconsistent and refer to him using both names. In this narrative, I have chosen to call her by the name June and him by the name James.

[2] For more about the Love and Rhyne families of Gaston County, North Carolina, refer to the chapter “Labor of Loves” in Allen Tullos’ Habits of Industry. The chapter chronicles several generations of the family’s history, with early generations working as farmers, subsequent generations as merchants and mill-owners, and culminating in Spencer Love’s development of Burlington Industries.

[3] Love, Recollections, 174-175, 207-213.

[4] Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II, 284.

[5] James Monroe “Magnus” Spencer” was a native of Clinton, Alabama, and came to Chapel Hill in 1849 to study law. Spencer is emblematic of the University in the era that he attended. In the 1840s and 1850s, the University grew significantly, with a third of the students coming from across the South. University historian Kemp Battle noted that the student body grew from 1,602 matriculants in the decade from 1840 to 1850, to 3,480 in the decade from 1850 to 1860, with the largest number of out-of-state students coming from Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, in that order. This development was driven by the economic prosperity of plantation crops like cotton, doubled with “the want of public confidence in colleges South of our State” (Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Volume I, 644-645). Magnus Spencer and Cornelia Phillips married in 1855 and moved to his hometown, where he established a law practice. Their daughter was born in 1859, but these years were fairly unhappy, with Cornelia feeling deeply out of place socially in Alabama, and Magnus suffering from spinal meningitis from 1856 until his death in 1861. Cornelia and June Spencer returned to Chapel Hill, but the town they arrived in was significantly changed by the present war.

[6] Love, Recollections, 192-194.

[7] Cornelia Phillips’ mother is alternately referred to alternately as Julia and Judith in various sources

[8] Wright, “The Grown-up Daughter,” 262.

[9] Wright, 278-281.

[10] Love, Recollections, 181, 211.

[11] Love, Recollections, 181-182, 256-262.

[12] Senlac, at 203 Battle Lane, was Kemp Battle’s home, and the Loves would live there for several months in 1887. Kemp Battle’s father, Judge W.H. Battle, was founder of the University’s Law School, and built the home in 1843. It was the President’s House during Battle’s tenure from 1876 to 1891, and became the Baptist Campus Ministry (Snider, Light on the Hill, 109) (National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, pg. 33, http://www.townofchapelhill.org/home/showdocument?id=26205).

[13] Love, Recollections, 207-213.

[14] Love, Recollections, 233.

[15] Love, Recollections, 209-210.

[16] Both James’s memoirs and a letter to June from their daughter refer to Venable as the “more prudent” choice.

[17] Love, Recollections, 196-202.

[18] Wright, 280.

[19] Love, Recollections, 201.

[20] For more about Love’s choice of teaching mathematics, refer to pages 214-15 in Recollections.

[21] This funding facilitated the addition of four full professorships, in Law, English, Education, and Mining and Metallurgy, and two assistant professorships, in Botany and Zoology, and Mathematics. (Love, Recollections, 232).

[22] info re. Johns Hopkins…

[23] Love, Recollections, 232.

[24] A description of some of the criticism of Love’s selection: “When the result of the election became known there began to flow a torrent of ill natured criticism, of a very trivial nature, mostly from those who had opposed the State appropriation [of the Land Grant endowment]. One editor complained that while four Christian bodies were represented in the Faculty, and his smaller denomination not at all, it had offered a good man as a candidate and he was not chosen. This preference of another must have proceeded from favoritism, the successful candidate being a son-in-law of a lady long identified with the University. President Battle was sharply criticized. The answer to this was, first, that it was impossible, as well as improper, to choose a professor to gratify a religious body, that if this rule should be adopted it would probably be at the sacrifice of efficiency; that there were many denominations whose claims were as strong as that now asking for recognition, and finally, that Mr. Love, in the opinion of the Board of Trustees as well as the Faculty, was the best man for the place. In stating facts showing this superiority President Battle did only what all college presidents habitually do and ought to do” (Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Vol. II), 335-336.

[25] Love, Recollections, 238-241.

[26] Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Vol. II, 366.

[27] Similar leases were made to Rev. Dr. Thomas Hume, Dr. Charles Baskerville, and Dr. Francis K. Ball. Later, on different legal advice, the University began selling lots outright to faculty, including Dr. George Howe, Dr. Joseph H. Pratt, Dr. A.W. Wheeler, Mr. George F. McKie, and Mr. Edward K. Graham; the original leases made to Love, Baskerville, and Ball were also sold outright from the University (Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II, 366). The many of these houses are included in the [name] Historic District, and short histories are available on the Preservation Chapel Hill website.

[28] Archeological report, 2004, pg. 15-17.

[29] This house has been the subject of two different digs by archeologists at UNC: one undertaken in July and August 2004 during the renovation of Love House, and a second undertaken in the driveway of the current UNC system President’s House during construction in August 2014. [links to archaeological reports from 2004, 2014]

[30] The Second President’s House was home to President Caldwell, President Swain, Prof. Patrick, Dr. Charles Phillips, Prof. J. deBerniere Hooper, and finally, Rev. Dr. Thomas Hume.

[31] UNC Trustees Minutes, pg. 302; April 20, 1887

[32] Archeological report, 2004, pg. 18-19.

[33] UNC Trustees Minutes, pg. 302; April 20, 1887

[34] UNC Trustees Minutes, pg. 177; February 21, 1900.

[35] Archeological report, 2004, pg. 18-19.

[36] Love, Recollections, 238-241.

[37] Love, Recollections, 238-241.

[38] James Love recalled some of the writing Cornelia Spencer did in Love House:

“Just before we moved into the new house in 1887 Mrs. Spencer accepted a commission from a Raleigh publisher…to prepare a short history of North Carolina for use in Elementary Schools….She had been, for some years, and continued until the work was finished in 1889, engaged upon the preparation and publication of a directory, or list, of all alumni and officers of the University. She must have worked some ten years on that directory. She wrote all the letters of inquiry and did all the clerical as well as directional work on it, under the supervision of President Battle. It was printed for the Centennial in 1889.

“The University supplied postage, and in part, at least the stationery for the voluminous and prolonged and tedious correspondence. Mrs. Spencer received, I believe, no pay whatever, for her services. If there was any pay, at all, it was a pittance; but I feel very sure she was not paid. Nor did she expect or desire pay for it. To her it was a labor of love. She had personally known multitudes of the alumni; and, in the forced seclusion caused by her deafness, it was a renewal of old associations to gather up the threads and follow clues of information; and a joy to her to serve the University.

“This catalogue was her ‘steady job’ for some time before I first met her until it was ended in 1889; and after that, she was always culling information and adding notes to her copy of the ‘Alumni Directory’ – or ‘Alumni Catalogue.’ She was proud and pleased with the result – and well might she be.

“She began the North Carolina History about 1887. I can’t get the exact dates; but I know that, after we got into the new home, she spent all her time working on it, until the whole manuscript, all in her neat legible handwriting was ready for the printer. Mrs. Spencer always wrote on her lap – on a ‘portfolio’ or tablet. I never knew her to sit by a table or desk to write” (Love, Recollections, 256-262).

[39] Love, Recollections, 256-262.

[40] Love, Recollections, 238-241.

[41] Geiger, The History of American Higher Education, 283.

[42] The Land Grant Act is often called the Morrill Act, in honor of Justin Smith Morrill, a Representative from Vermont, who crafted the legislation. [Expand to mention the later Land Grant Act]

[43] Geiger, The History of American Higher Education, 281.

[44] Graduate study was already part of the German education system, and a number of early American Ph.D.s earned their degrees at German universities.

[45] Geiger, The History of American Higher Education, 325.

[46] The legislative battle that lead to this decision is chronicled in Chapter II “The Land Scrip Fund” of Kemp Battle’s History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II, pages 64-73.

[47] “The college is doing a useful and valuable work, but is not doing the work of the University of North Carolina. This University is doing a most useful and valuable work but it ought not to confine itself to agricultural and mechanical teaching” (Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II, 384). Further reading on the University’s struggle with the Land Grant funding and requirements is found on pages 122-124, 214-220, 220-230, 374-384. A particular point of political contention was whether the University had sufficiently expanded its curriculum to fulfill the requirements of the Land Grant Act. On pages 220-230, an 1881 report entitled “The University: its Origin, its History, its Work, its Needs, and Reasons for its Existence” defended the University, its utility and its implementation of the Land Grant endowment, to the General Assembly.

[48] The political campaign that lead to this re-appropriation of funds is recalled on pages 374-384 of Battle’s History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II. For further perspective about how this event is remembered, see NCSU’s narrative about its founding.

[49] This same cultural dynamic played out at many public institutions across the country.

[50] Love, Recollections, 240-243.

[51] In Recollections, Love does not mince words in describing the “personal antagonism” of Venable, Winston and Manning toward him. In particular, he recalled that Venable “had been my unsuccessful rival in love and wanted to get me out of Chapel Hill — for a long time he was not on speaking terms with June and Mrs. Spencer — he had a mean, sullen, smallness of soul so he couldn’t forgive me and June” (Love, Recollections, 244). He explained that Manning’s motivation was because he was Venable’s father-in-law, but he also gave a further searing indictment:

“Manning was head of the Law Department of the University [and]…he had served a term as Representative from a North Carolina District in the U. S. Congress. He was also a member of the Board of Trustees, and had been a member of the Committee of that Board to decide on the reductions in the faculty made necessary by the loss of the $7500.

“I thought then, I think still, that Dr. Manning…occupied at that time a role that a man of sensitive honor could not hold — being a member of the faculty and a member of a Committee of the Trustees to sit in judgment on the members of the faculty.

“I did not understand how public opinion could “stand for it” — I cannot explain it now, unless it was true that he had strong personal influence in the Board, was not sensitive to the proprieties of the situation, and was willing to occupy his dual role in order to save his own position; for, it should be noted, his own chair was created at the same time [as the professorships created in 1885] — which…his Committee cut off” (Love, Recollections, 245).

[52] Love, Recollections, 246.

[53] Love, Recollections, 249-250.

[54] Love, Recollections, 249.

[55] Love, Recollections, 246-248.

[56] now Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

[57] Love, Recollections, 318.

[58] Love, Recollections, 317.

[59] Oral history

[60] The transcript of the interview shows this passage as, “…they knew that the southern schools couldn’t prepare my brother and me.” However, the audio sounds like, “…they knew that the southern schools couldn’t compare.”

[61] Oral history

[62] http://www.historync.org/laureate%20-%20James%20S.%20Love.htm

[63] Tullos, Habits of Industry, ?.

[64] Love, Recollections, 293.

[65] Love, Recollections, 270.

[66] Citation; http://video.unctv.org/video/2365079383/, starting 12:53

[67] Love, Recollections, 295.

[68] http://ncpedia.org/biography/whitehead-richard-henry

[69] http://mainstreet.lib.unc.edu/projects/chapelhill/index.php/markers/view/41

[70] http://www.preservationchapelhill.org/?_escaped_fragment_=pool-patterson-house/caw3#!pool-patterson-house/caw3

[71] same resource as block quote below

[72] citation

[73] Extensive research has found no definitive records other than census data on the Stainbacks.

[74] Cite county records

[75] need citation

[76] Love, “Chatham County, Community at the Crossroads.” Spencie Love was acting director and assistant director of the Southern Oral History Program from January 1998 to May 2000.

[77] Dynamic Decade, pg. 73

[78] email from Moeser to John Powell; 11 Sept 2003 “A couple of things” (doc: 2015-11-23 15.34.54.jpg)

[79] The Martha and Spencer Love Foundation is a philanthropic organization initially funded by one-third of the estate of James and June Love’s son Spencer (1896-1962), who started and ran Burlington Industries; it’s also named in honor of his widow. Spencer Love served on the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina from 1947 until his death in 1962. http://ncpedia.org/biography/love-james-spencer

A booklet from the fundraising campaign for CSAS entitled “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill” included a tabulation of “development goals” including construction on Love House, totaling $913,000, of which $788,000 had already been pledged.

[80] The Bell Award was given to women who have made outstanding contributions to the life of the University.

[81] https://alumni.unc.edu/news/moeser-to-retire-award-named-for-spencer/

[82] “Rethink the Cornelia Phillips Spencer Bell Award: Why does UNC celebrate the contributions of women by honoring a racist?” (doc: 2015-11-23 16.26.58.jpg)

[83] https://alumni.unc.edu/news/moeser-to-retire-award-named-for-spencer/

[84] In a letter to Dr. Jim Leloudis thanking him for his work on the Remembering Reconstruction symposium in October 2004, Moeser reflected on goals for developing the University’s commemorative landscape. He wrote both, “I hold with those at Remembering Reconstruction who said, over and over again, let’s add to our history, not subtract,” and “Students, faculty and staff ought to see a campus landscape of buildings and monuments that reflect who we are today as well as who we were 100 years ago” (Letter from Chancellor James Moeser to Dr. Jim Leloudis, dated December 3, 2004). (doc: 2015-11-23 16.11.36)

[85] https://alumni.unc.edu/news/spencer-family-members-want-name-removed-from-dorm/

[86] Another result from this meeting was the development of “a campus committee…to recommend ‘how best to honor women at Carolina.’” http://www.greensboro.com/unc-chapel-hill-confronts-its-past-in-bell-dispute/article_01fed542-b90c-11e4-bbe3-774b4cea183d.html

[87] http://www.starnewsonline.com/article/20050123/NEWS/201230342

[89] “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill”

[90] “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill”

[91] “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill”

[92] “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill”

[93] http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/jun06/lovehutchins061506.htm

[94] Letter to Chapel Hill Town Manager, Re: Development Plan Modification No. 2 – Supplement #1; http://townhall.townofchapelhill.org/agendas/ca040517ph/1-%20add%20materials-unc%20mod%202%20supplement%201%20ltr%20pics.PDF

[95] “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill”

[96] The development campaign bulletin noted that the Love Foundation and Hutchins donations totaled $660,000, and separately that Glenn Hutchins’ donation toward the Hutchins Forum for the South was for $500,000.

[97] http://college.unc.edu/2015/11/30/celebrating-40-years-john-a-powell-77/

[98] Letter from Moeser to John Powell; March 15, 2002 (doc: 2015-11-23 15.28.51.jpg)

[99] context

[100] context

[101] http://ibiblio.org/pjones/blog/dedication-of-love-house/

[1] “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill”

[2] The Program in Southern Politics, Media and Public Life moved from the School of Journalism and Mass Communication to CSAS. The Program was closed in 2010 due to budget cuts to the University. (Program on Public Life of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill records, 1986-2010.)

[3] CSAS was housed in six different offices on different floors of Hamilton and Carroll Halls. (http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/jun06/lovehutchins061506.htm)

[4] Moeser Papers

[5] http://college.unc.edu/2015/11/30/celebrating-40-years-john-a-powell-77/

[6] http://south.unc.edu/programming/hutchins-lectures/james-a-hutchins/

[7] http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/jun06/lovehutchins061506.htm

[8] “Restoring the James Lee and June Spencer Love House: A Gift Proposal to the Friends of the Center for the Study of the American South at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill”

[9] The development campaign bulletin noted that the Love Foundation and Hutchins donations totaled $660,000, and separately that Glenn Hutchins’ donation toward the Hutchins Forum for the South was for $500,000.

[10] Letter to Chapel Hill Town Manager, Re: Development Plan Modification No. 2 – Supplement #1; http://townhall.townofchapelhill.org/agendas/ca040517ph/1-%20add%20materials-unc%20mod%202%20supplement%201%20ltr%20pics.PDF

[11] Letter from Moeser to John Powell; March 15, 2002 (doc: 2015-11-23 15.28.51.jpg)

[12] context

[13] context

[14] http://ibiblio.org/pjones/blog/dedication-of-love-house/